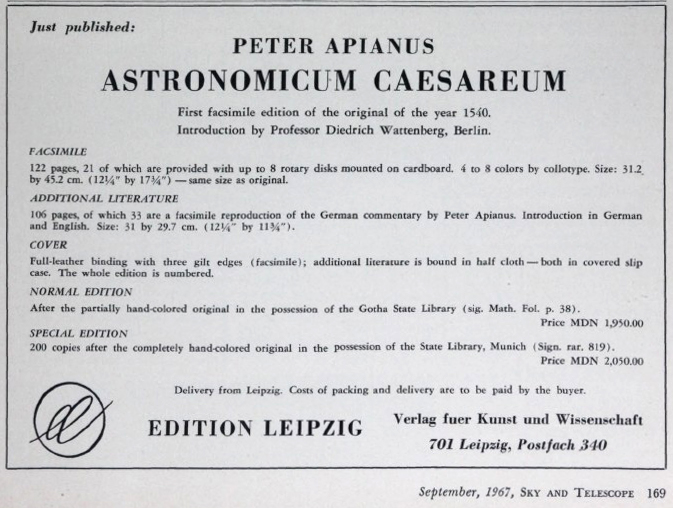

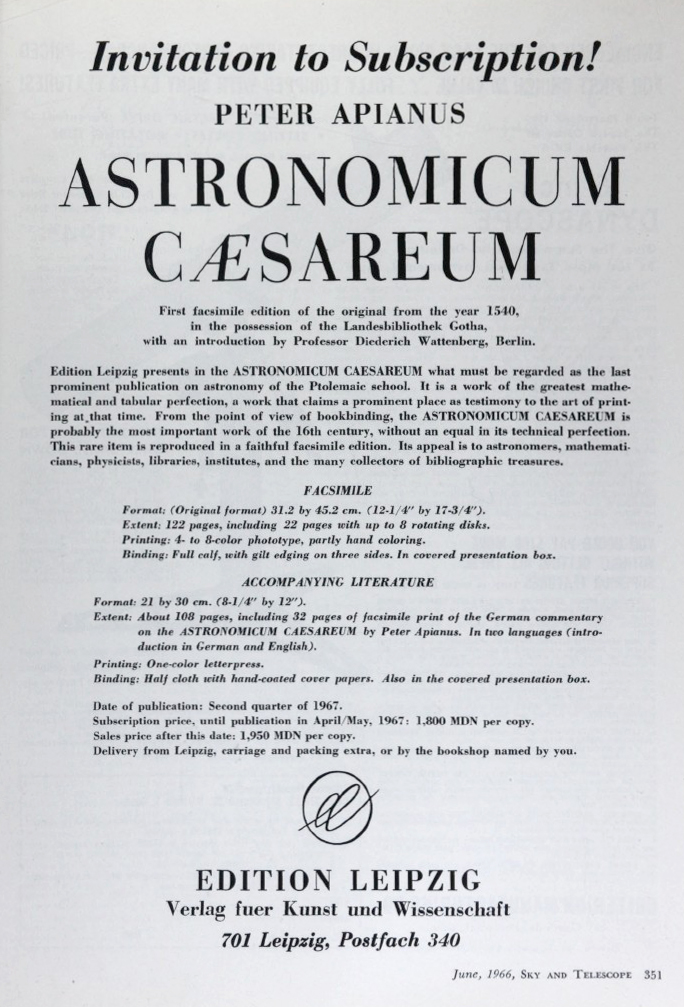

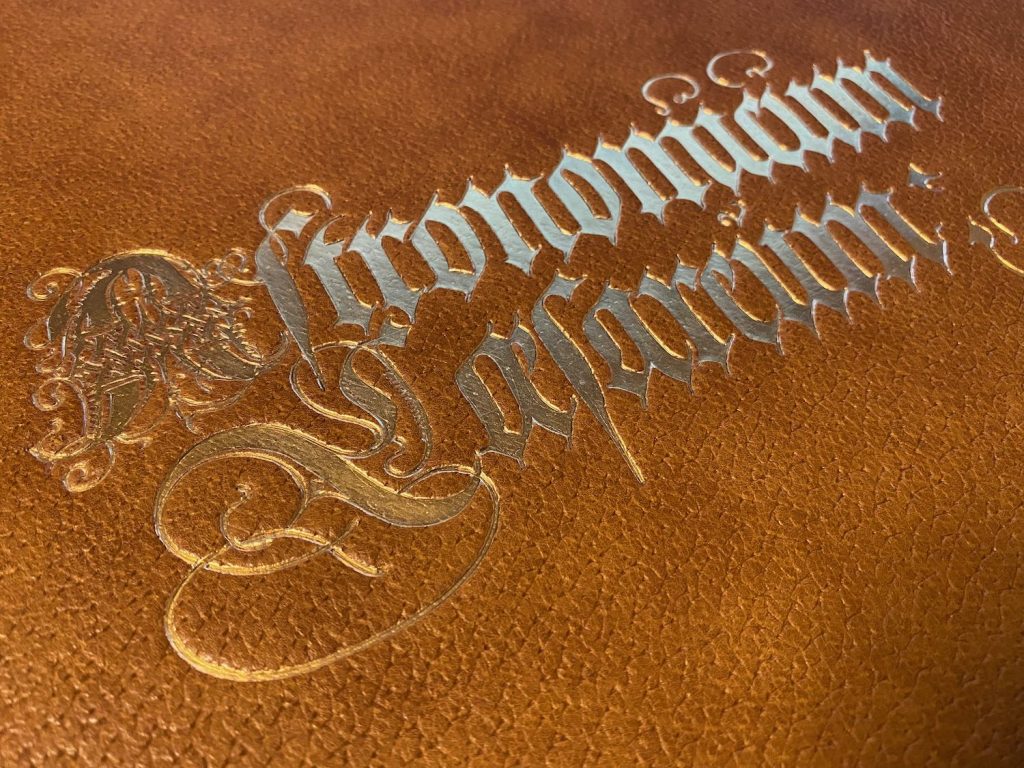

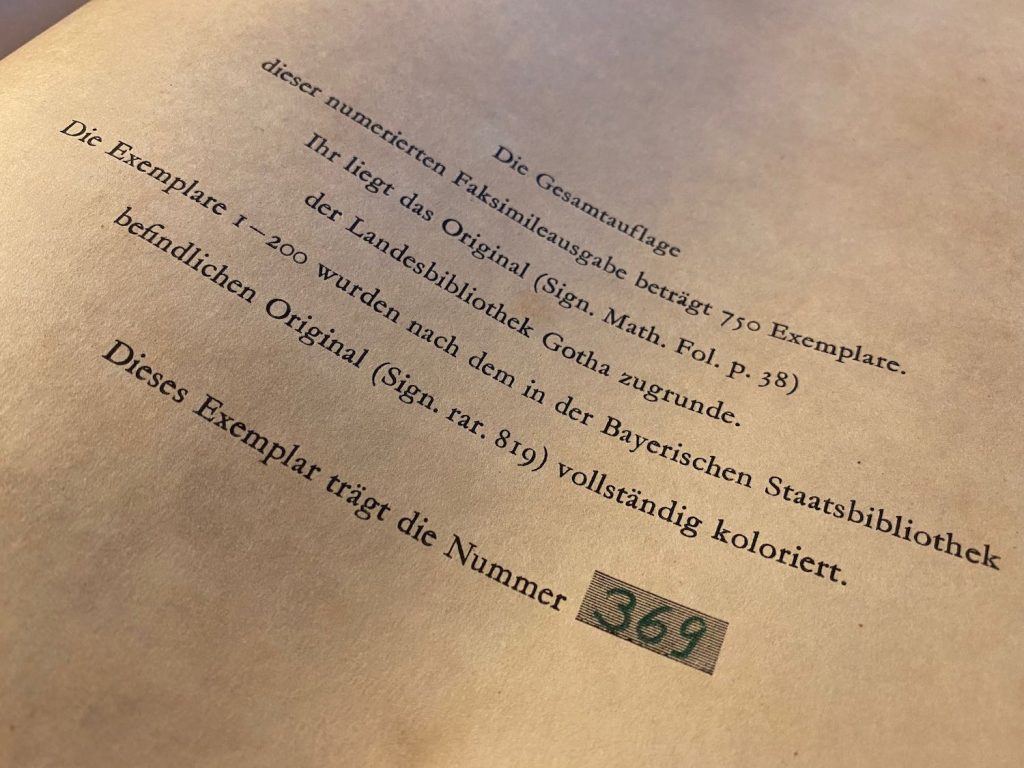

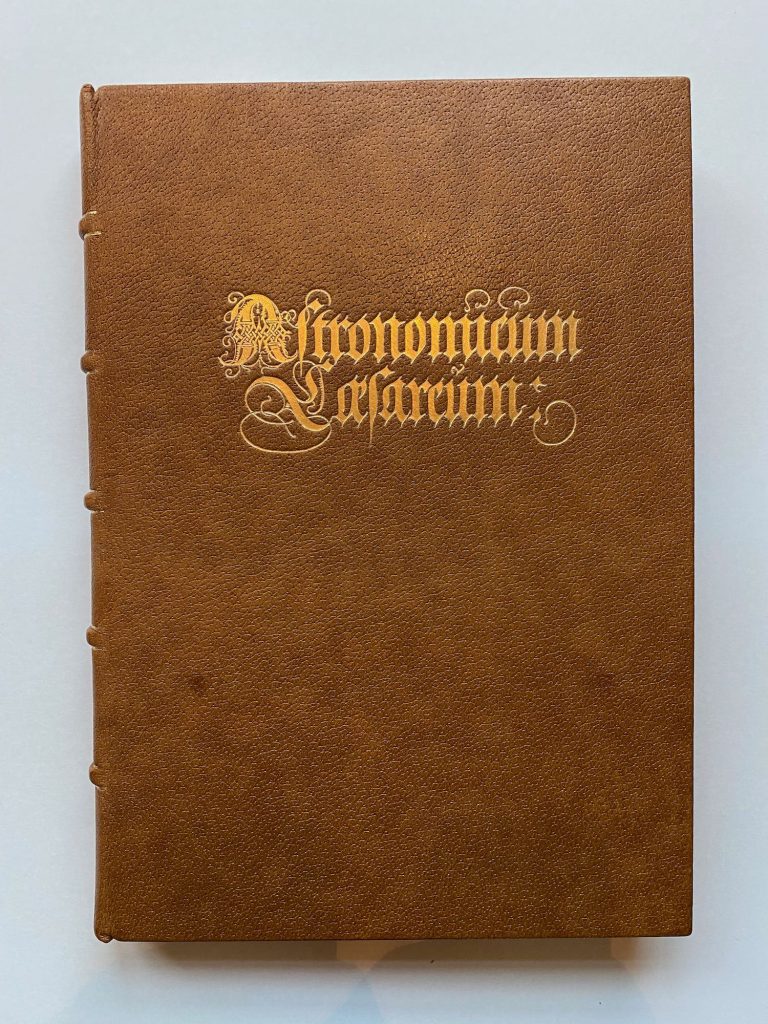

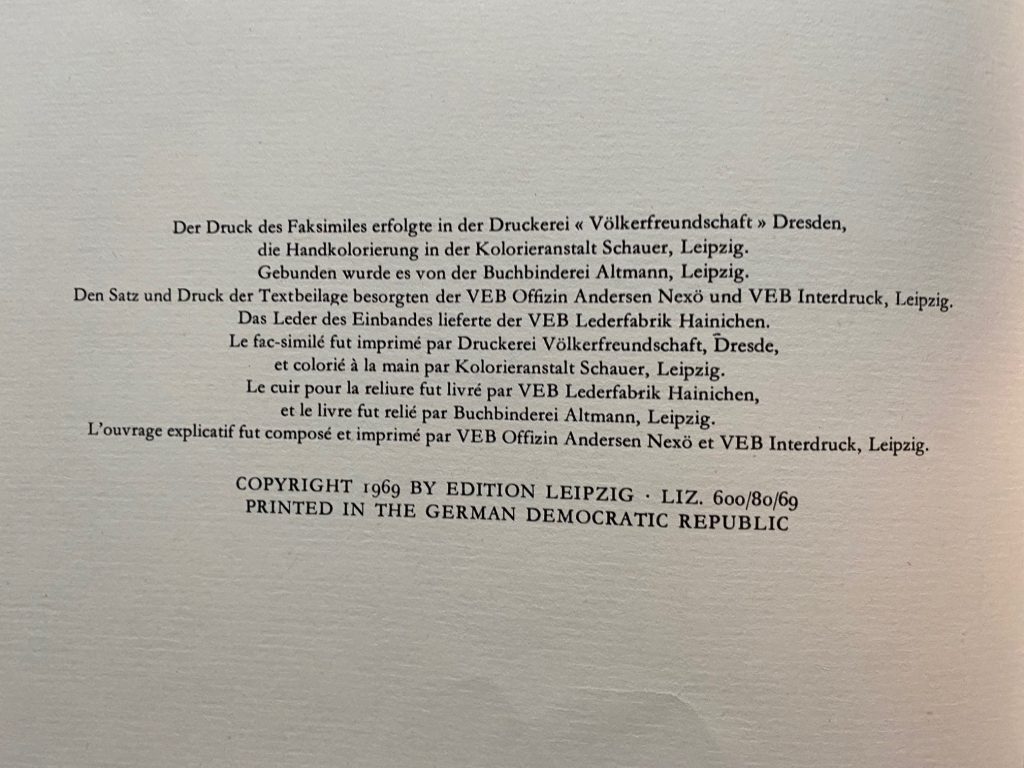

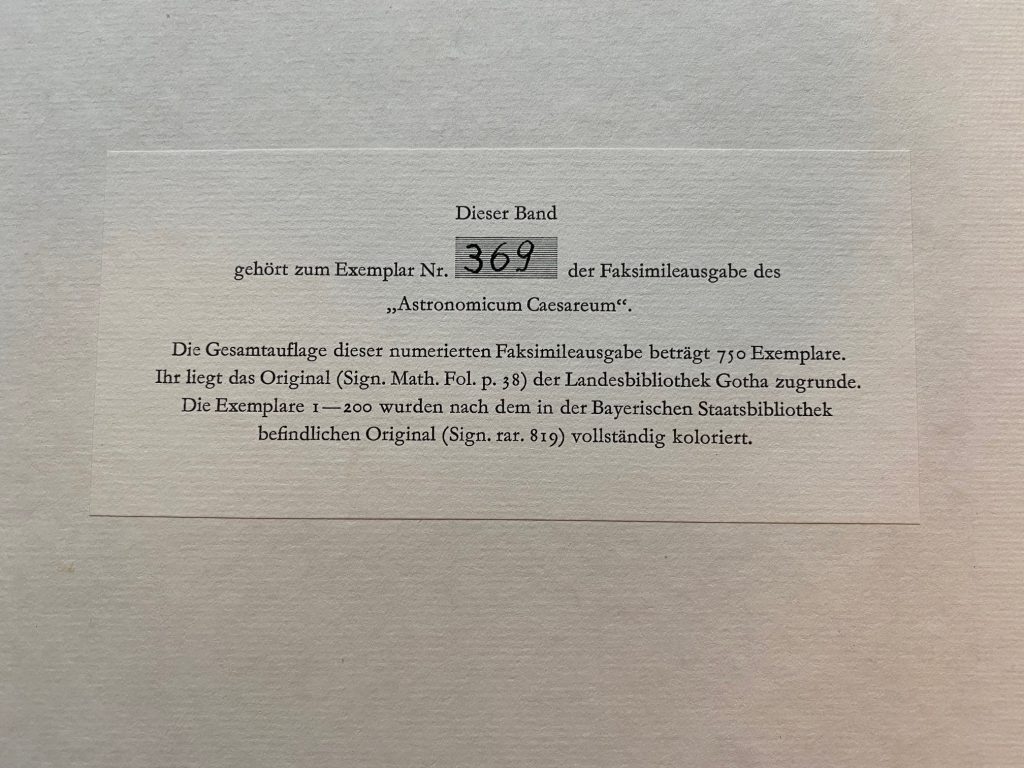

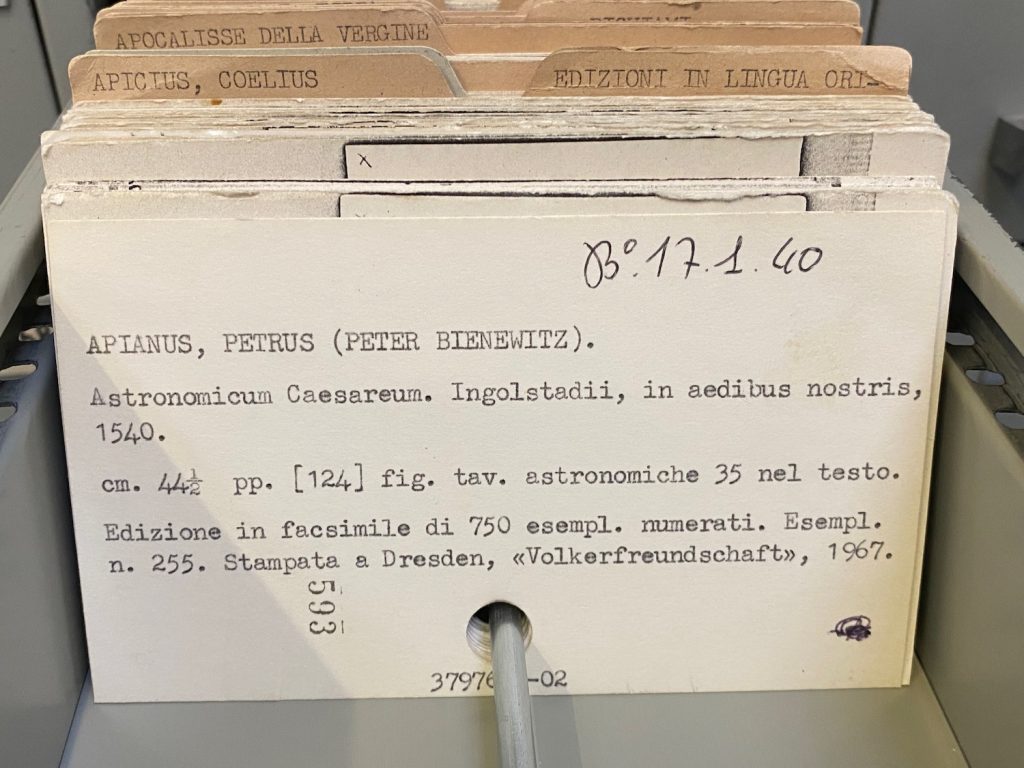

Mijn mooiste boekje komt van Novemberland uit Leiden. Jaap Schuurman is de eigenaar en zoekt soms met me mee. Lang gedacht over mijn toenmalige duurste boek. Nog steeds mijn mooiste. Nu heb ik via hem een facsimile gevonden van het origineel uit 1540: veruit het mooiste boek dat ik ooit vast heb mogen houden. Om zeker te zijn heb ik onlangs bij Museum Boerhaave een broertje bekeken, nummer 332. Toen besloten dat dit mijn ‘bitcoin investering’ is, maar dan waardevast ! Een facsimile is in feite een reproductie van het origineel, in dit geval dus van de Leipzig editie, gemaakt in 1967. Hoewel het dus geen heel oud boek is (55 jaar) wel een heel zeldzaam boek met een oplage van slechts 750 stuks. In die tijd werd het voor 750 Duitse Marken verkocht, een handgekleurde voor 1900 DM: al best wel een bedrag toen.

Inmiddels dus wel al 3 posts over dit boek: Eerst het origineel, toen een ‘inkijkexemplaar’ en nu die van mezelf… Allemaal de moeite waard.

> View this site in Google English <

Index: Snelkoppelingen binnen deze pagina

Het is nogal een lange pagina gewordende ruim 15.000 woorden. Daarom maar even een index gemaakt. Bekijk alles en scroll naar beneden (iets andere volgorde), of kies een interessante kopje en volg de link. Met de terugknop van je browser kom je weer uit bij deze index. Tip: kijk zeker ook even bij ‘Onderzoek’.

Over Astronomicum CaesareumOver mijn facsimile

Over het onderzoek

Overige informatie

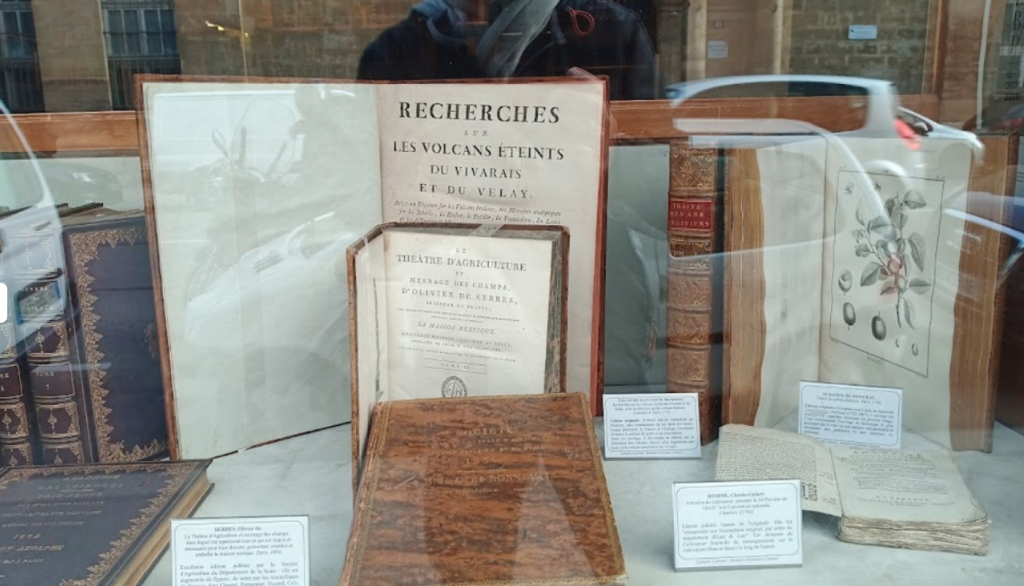

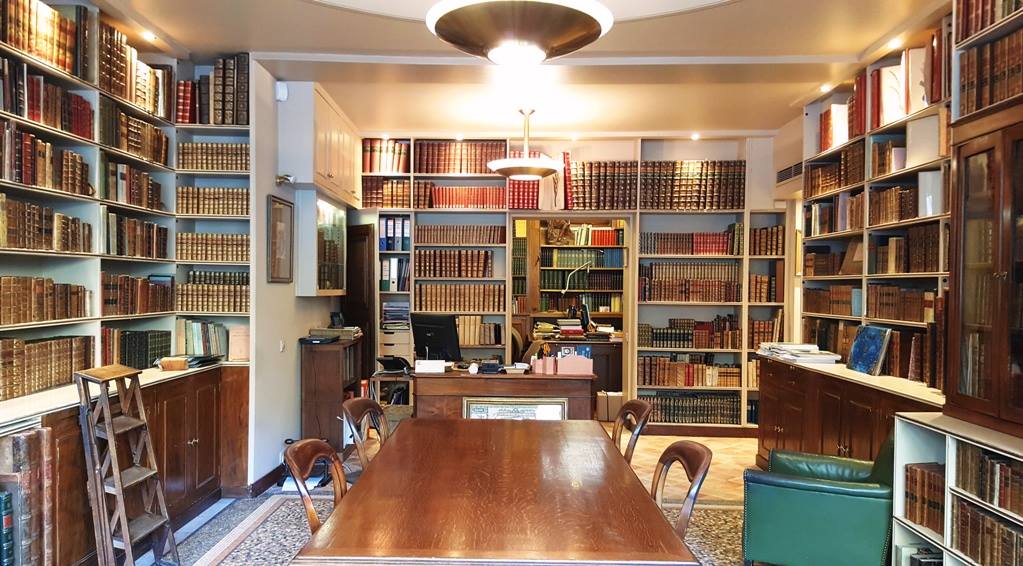

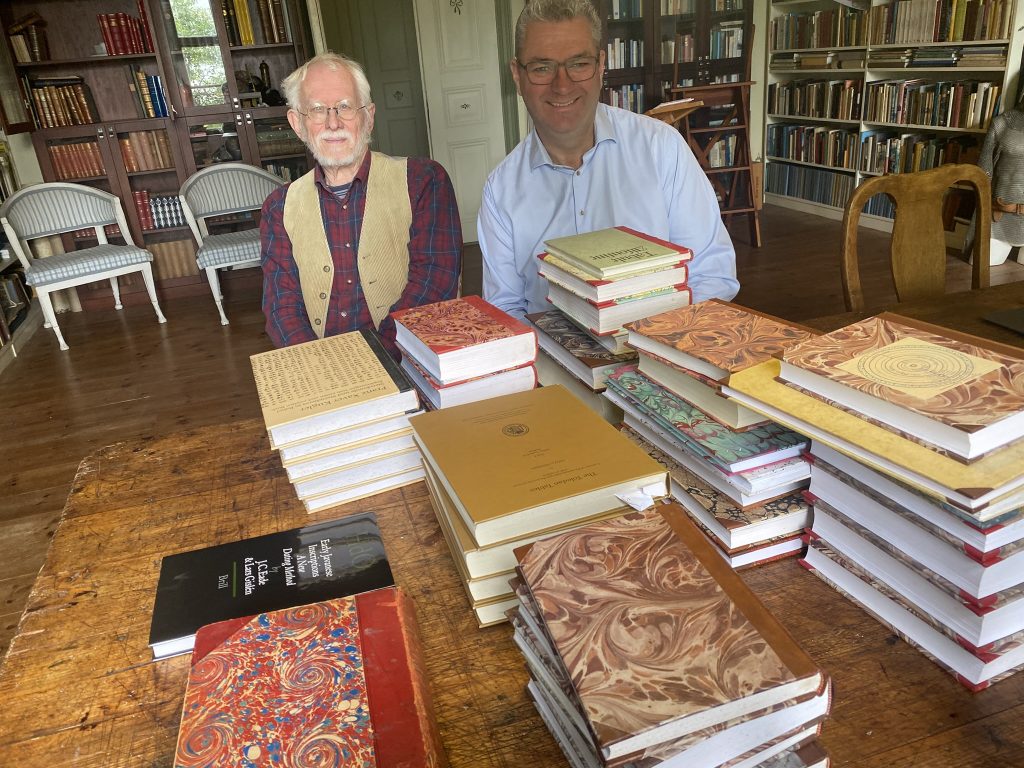

Librairie Clavreuil

Met al zijn contacten had Jaap een exemplaar gevonden in Parijs. Bij Librarie Clavreuil om precies te zijn. En om nog preciezer te zijn aan de Rue de Tournon nummer 19 in Quartier Latin. De boekwinkel bestaat al sinds 1901 en de derde en vierde generatie runnen de zaak nu: Bernard and Stephane Clavreuil. Deze laatste (4e generatie) heeft een vestiging in Londen geopend. Zij hebben het boek opgestuurd naar Leiden en daar kon ik het ophalen op 4 februari toen ik in Holten bij een klant op tijd klaar was… Gegevens antiquaar (goed geschreven, iemand die in antieke boeken handelt is blijkbaar geen antiquair, maar een antiquaar. Van Jaap geleerd…): Librairie Clavreuil, 19 rue de Tournon, Paris 75006, FRA, WEB: https://librairieclavreuil.com, Email: basane@librairieclavreuil.com, Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/librairieclavreuil/, Phone: +33 (0) 1 43 26 97 69

Over het origineel

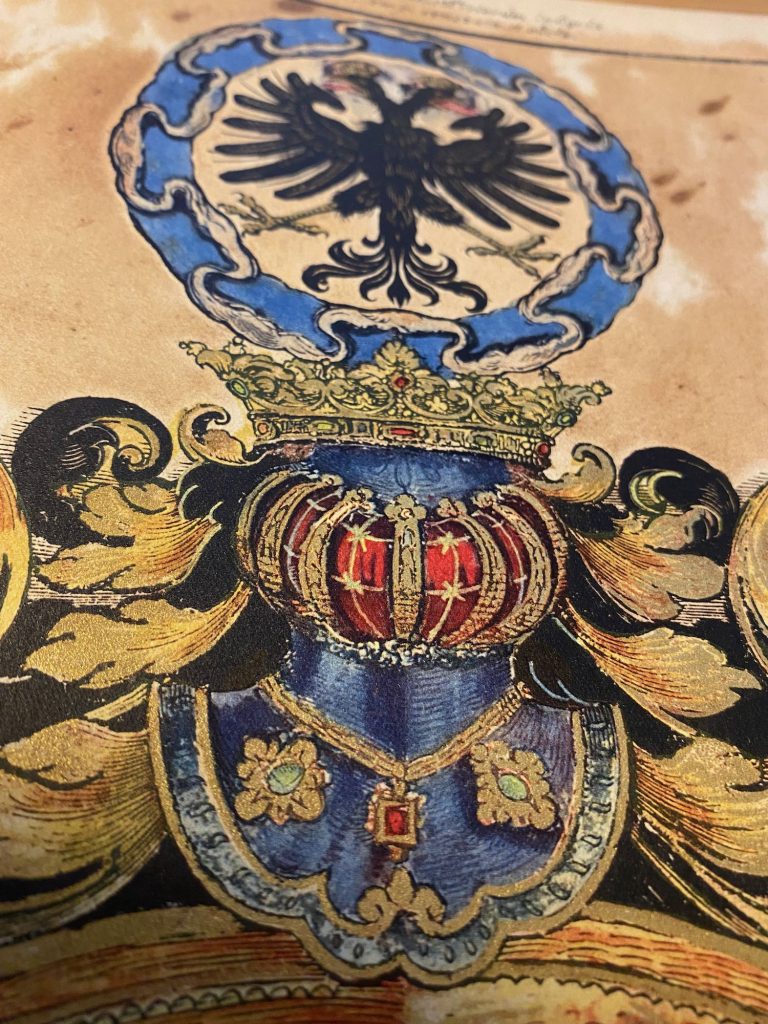

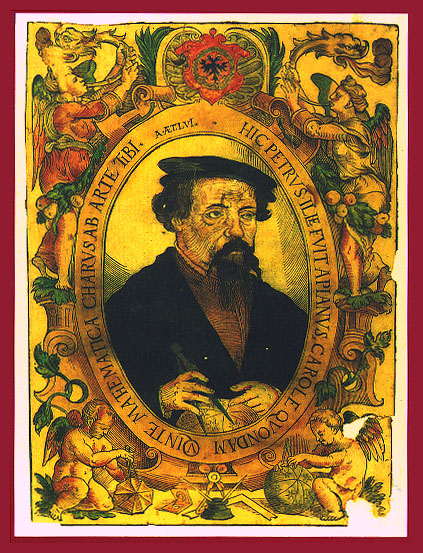

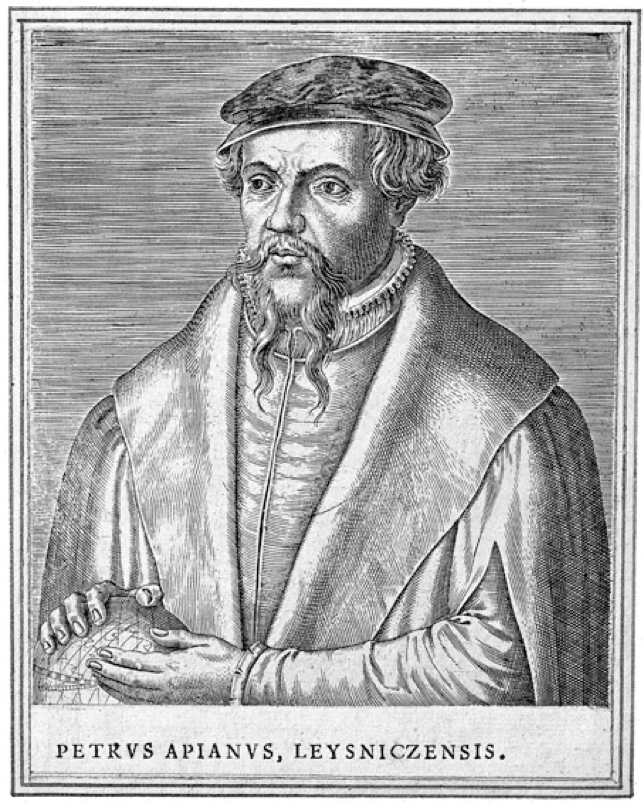

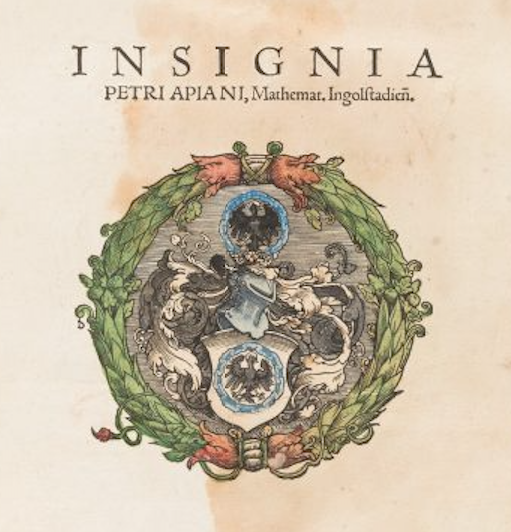

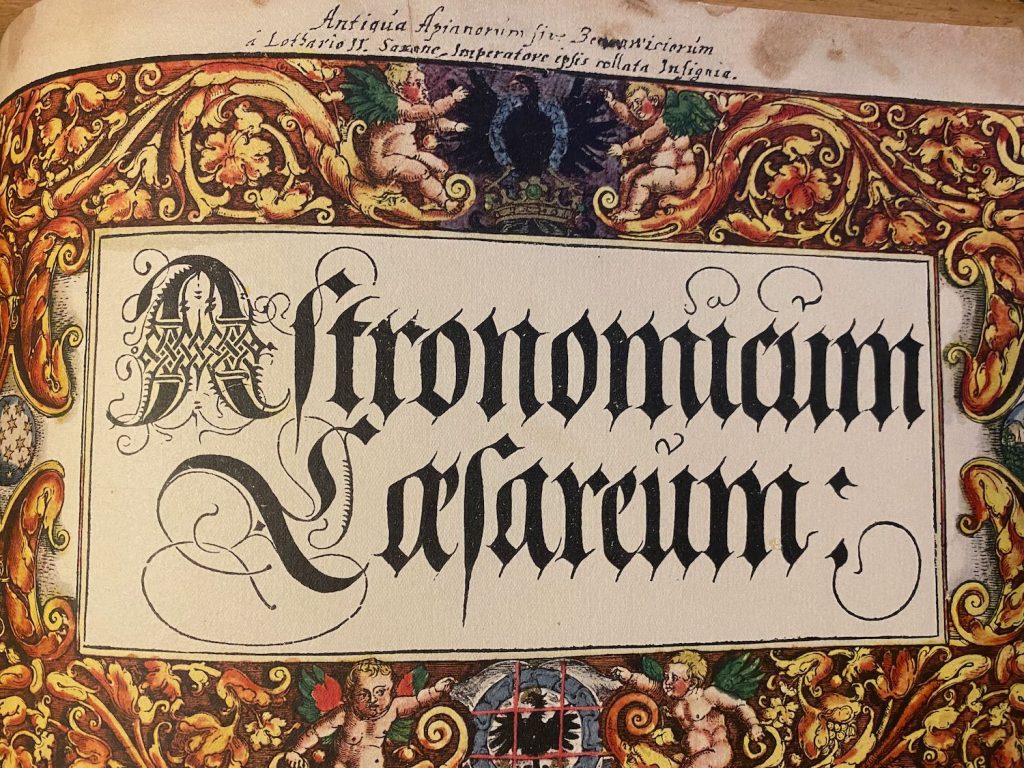

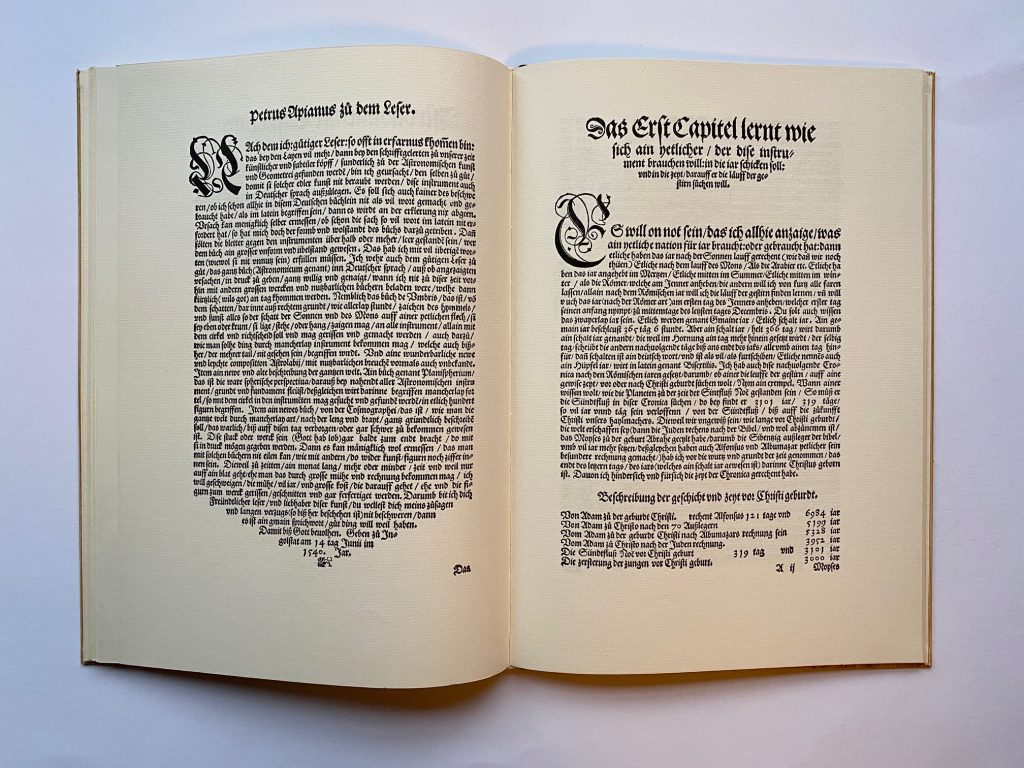

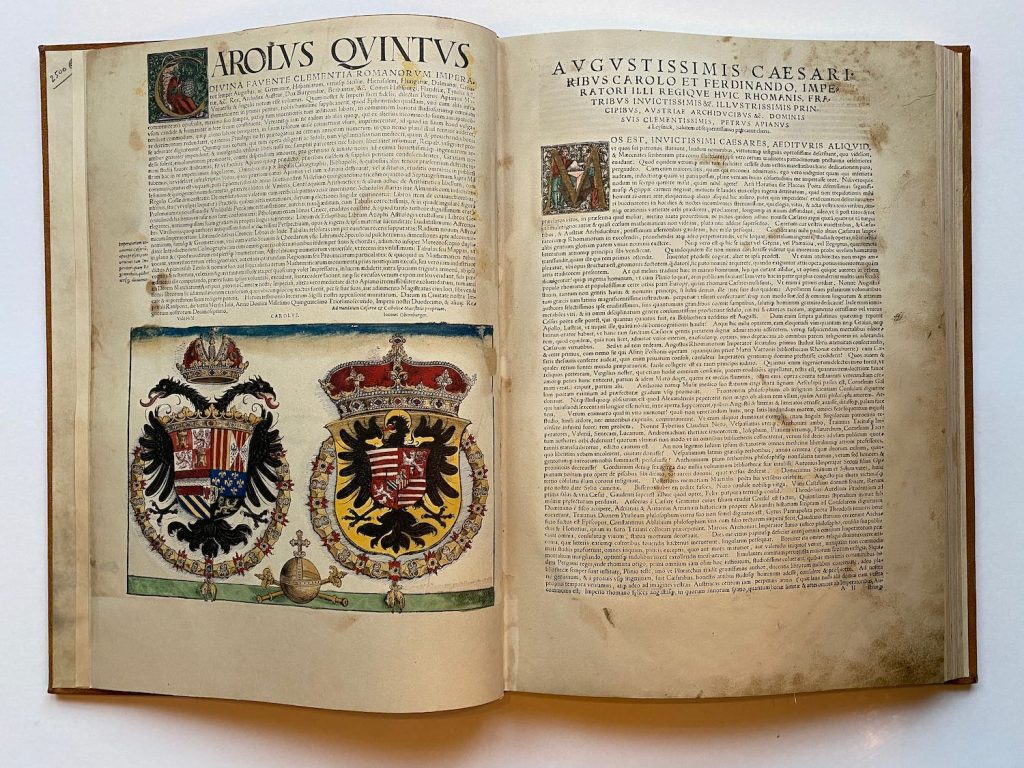

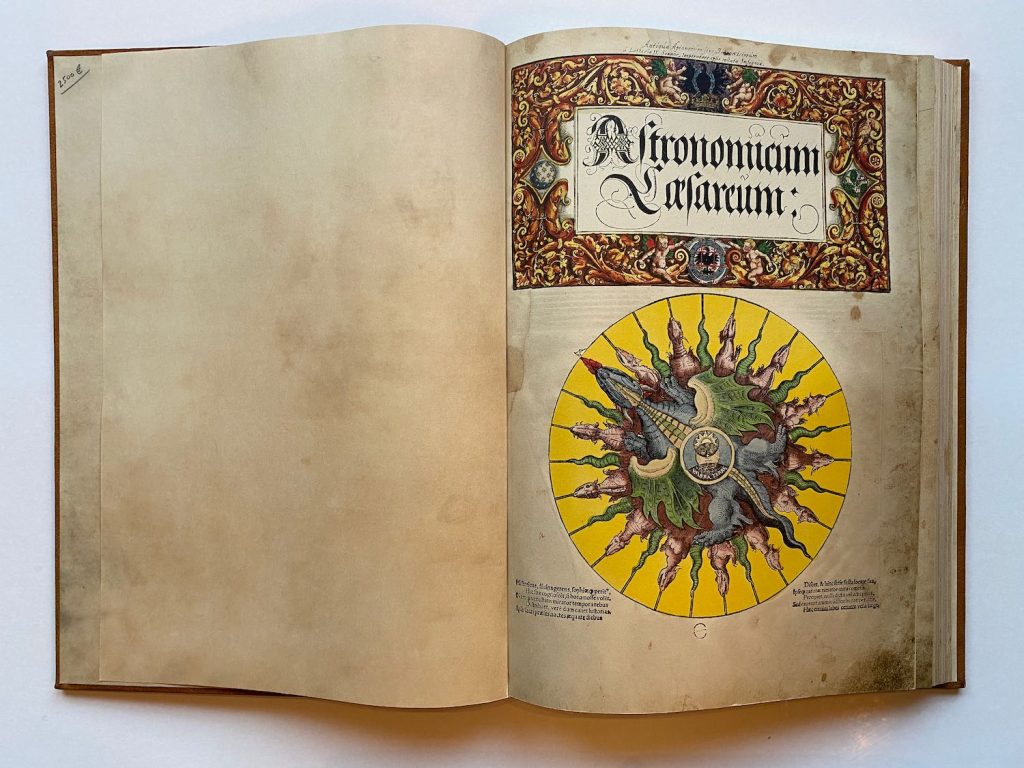

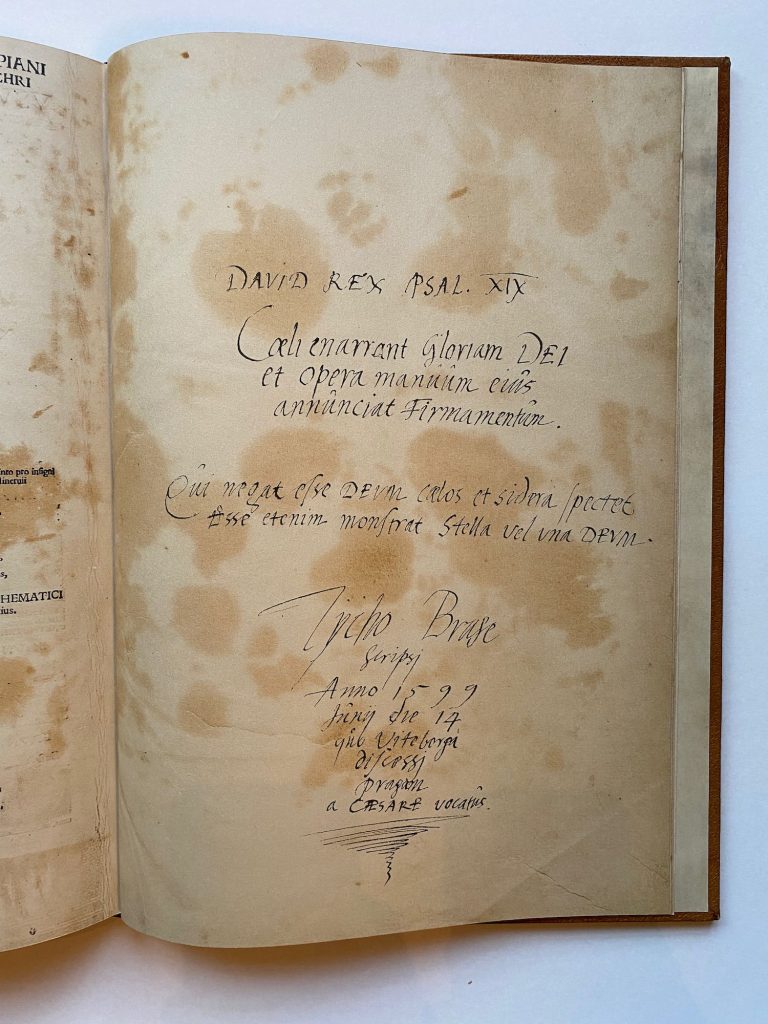

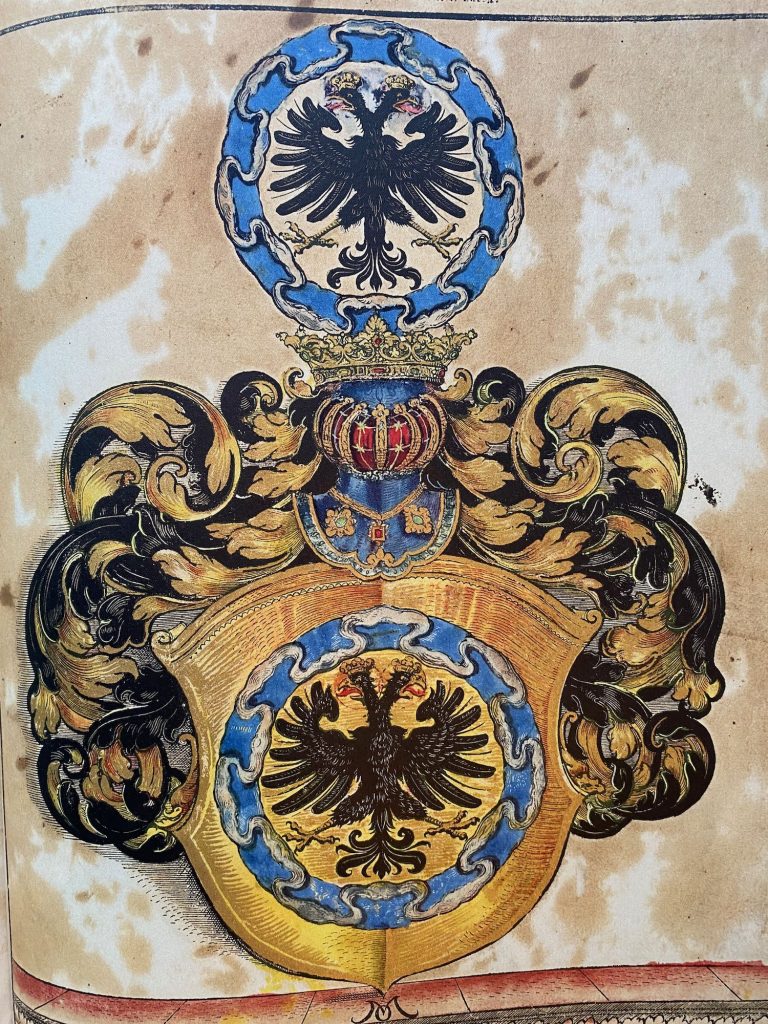

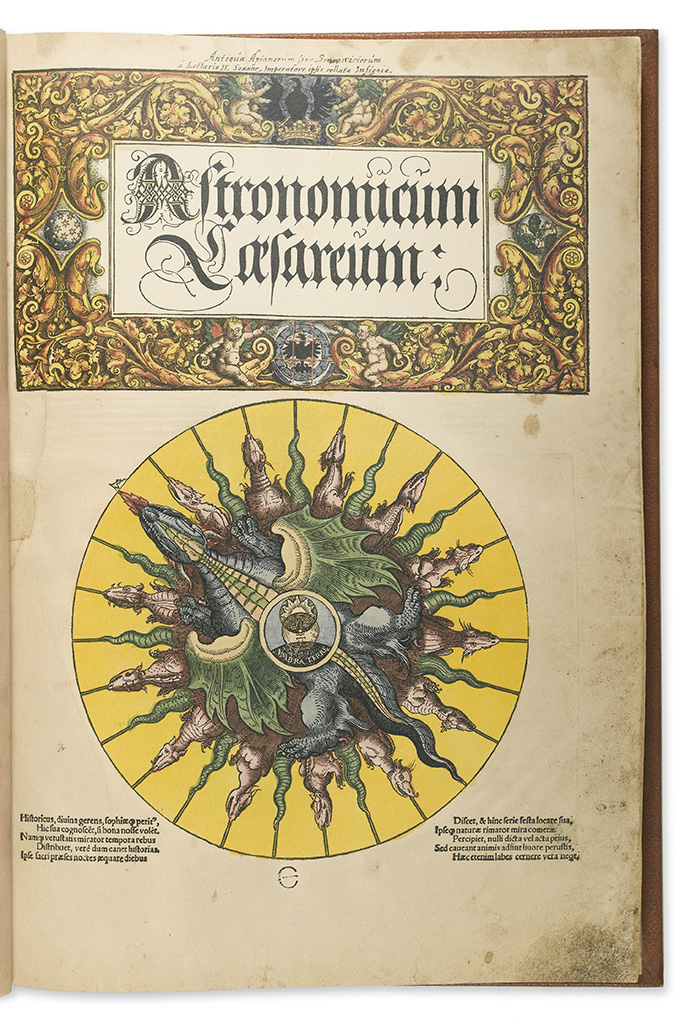

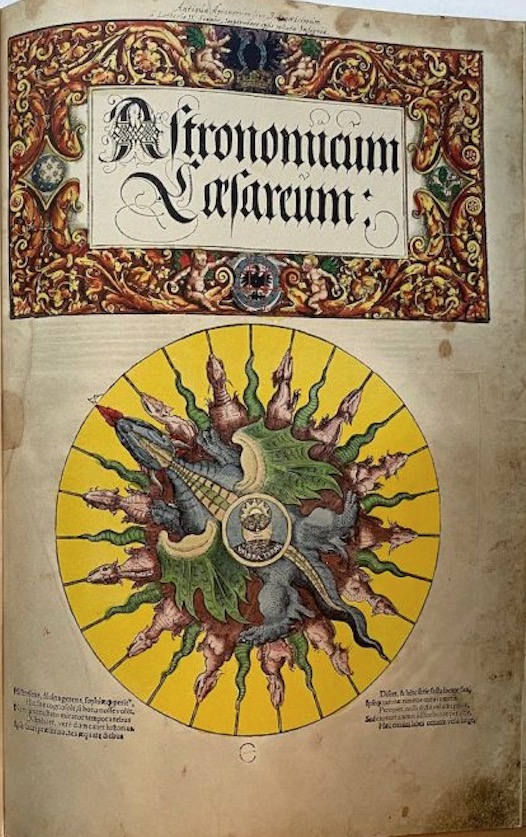

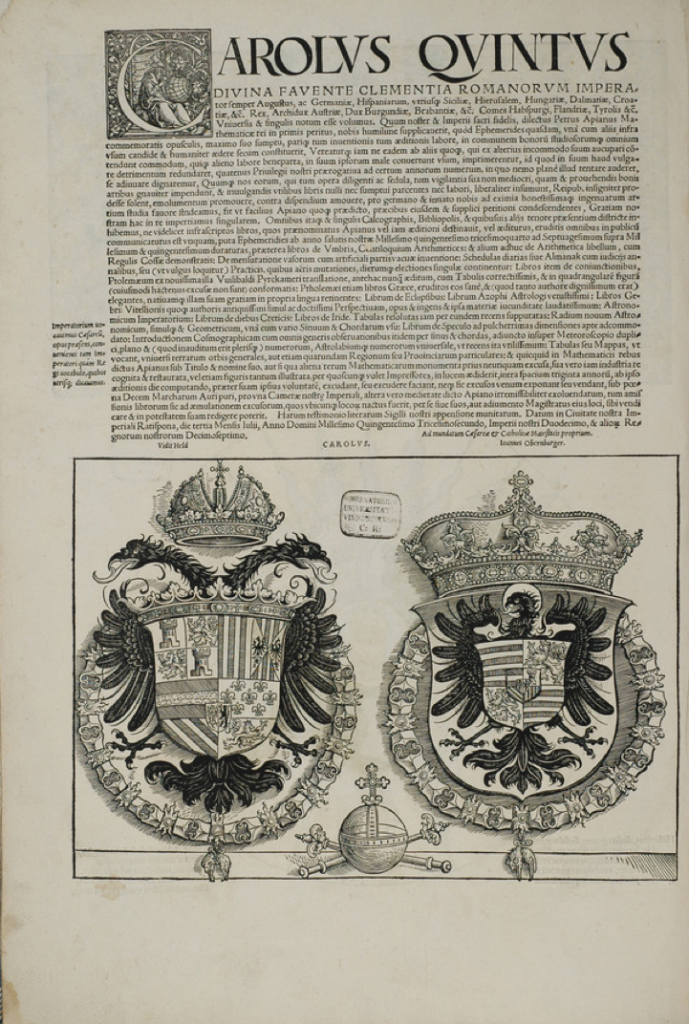

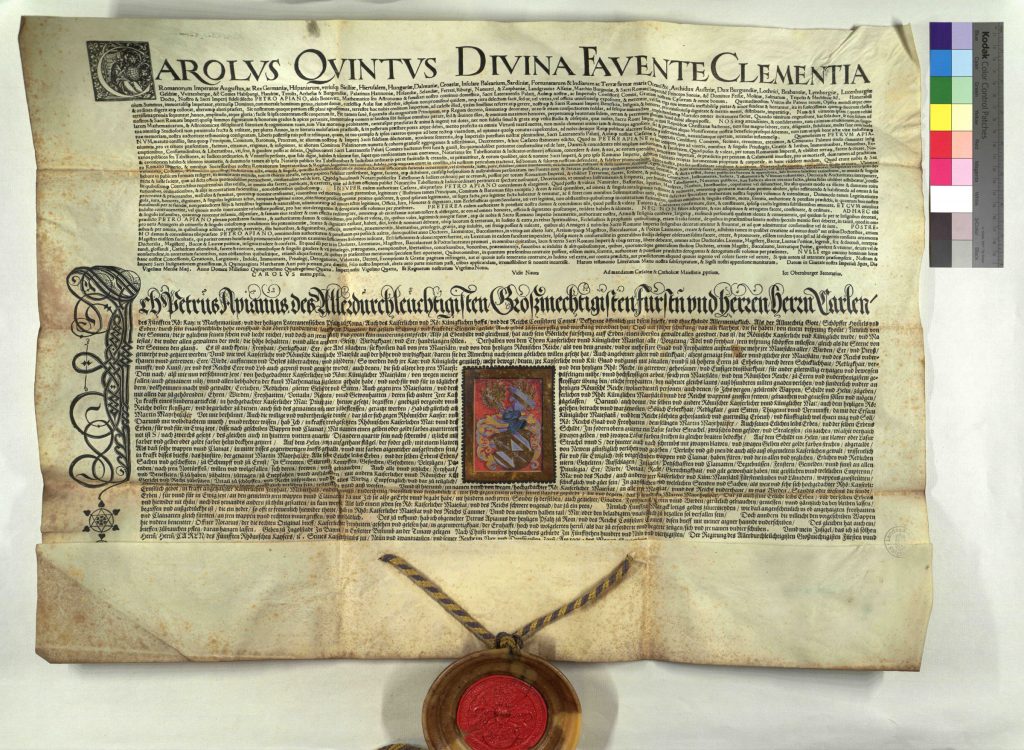

Petrus Apianus (Peter Bennewitz: Benne is bij in het Duits, Apia in het Latijn – 1495-1552) deed zo’n 8 jaar over het boek en er zijn er (volgens Owen Gingerich) waarschijnlijk 150 gedrukt, waarvan er naar verwachting nog 111 bestaan na een half millennium. Hij maakt het boek voor Keizer Karel en ontving daardoor een eigen wapenschild: zie laatste pagina van het boek. Apianus had een eigen drukkerij in Ingolstad. Ik heb in Leiden dus een origineel in mogen zien, later bleek dat ik meteen de laatste was die dat mocht, zo’n origineel wordt verkocht voor 850.000 euro in Wenen, vandaar… Hier een mooie PDF van een origineel boek, van het Duitse Museum in München.

Metropolitan Museum of Art: “De meest weelderige van alle leerzame handleidingen uit de Renaissance”

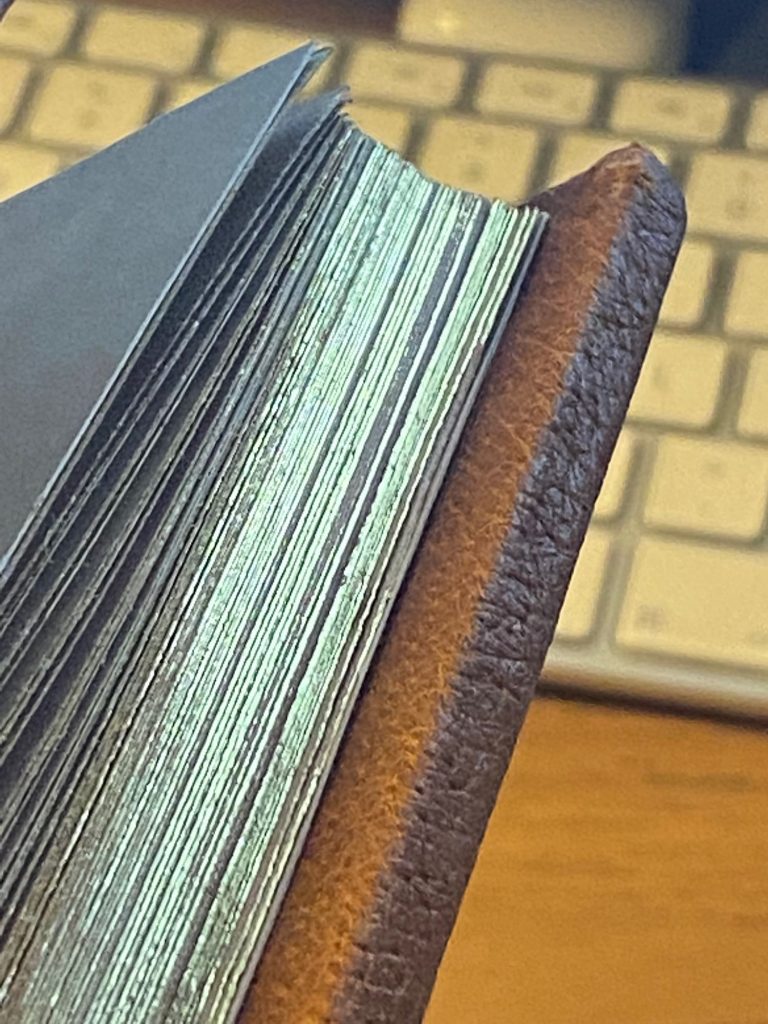

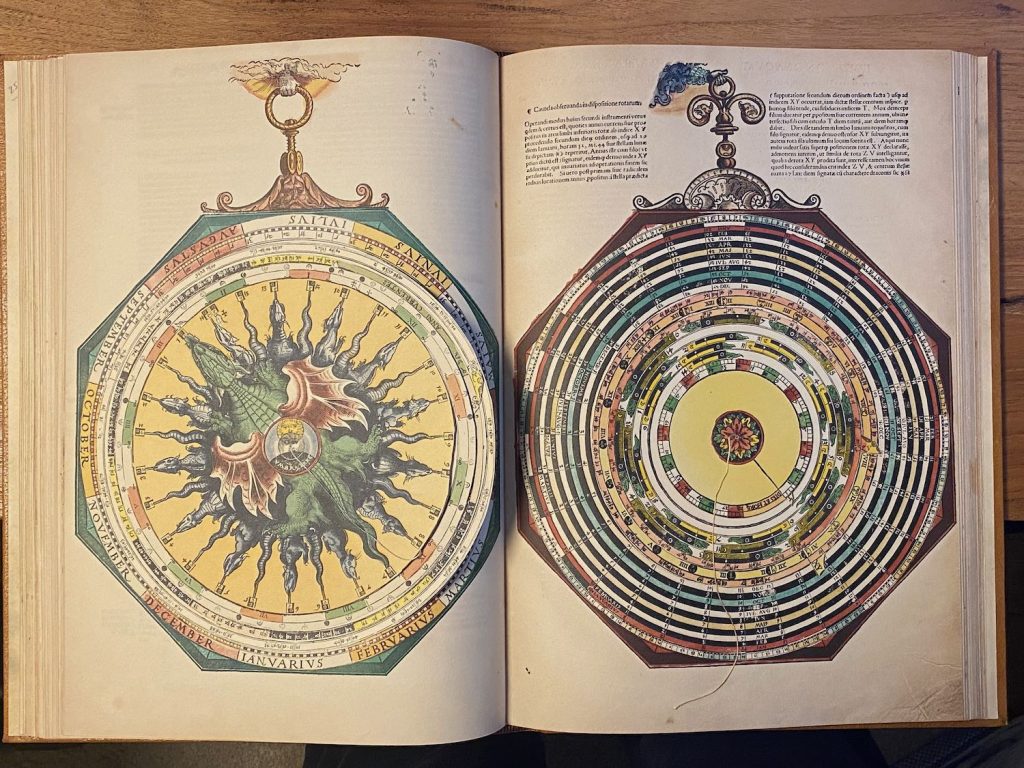

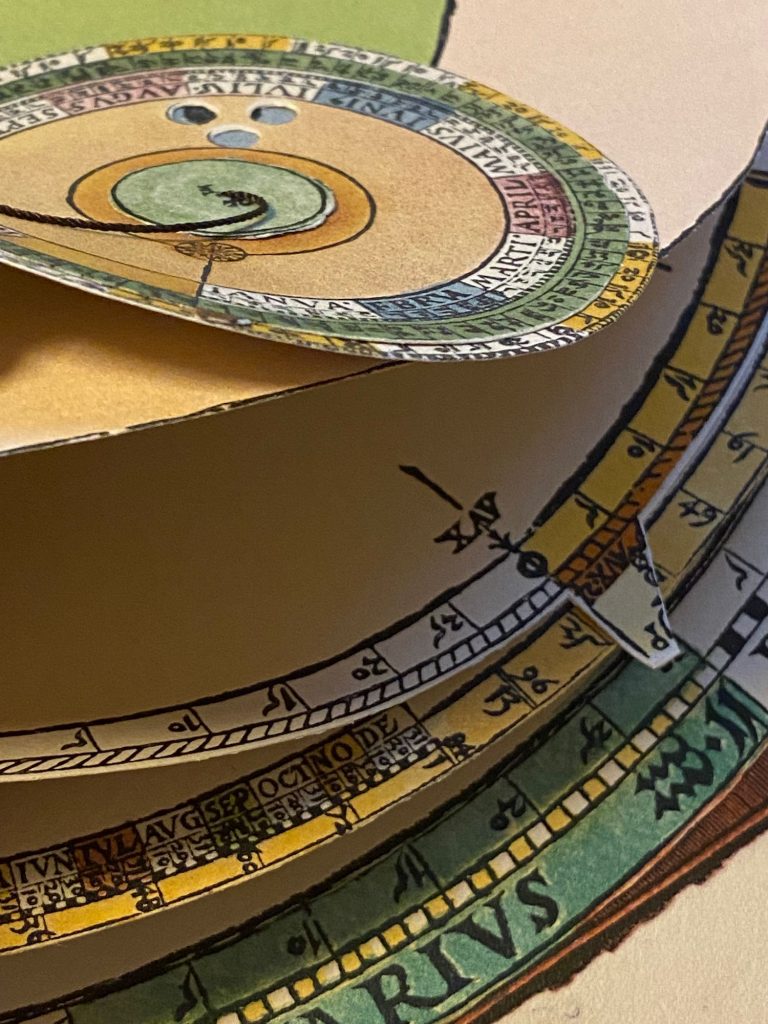

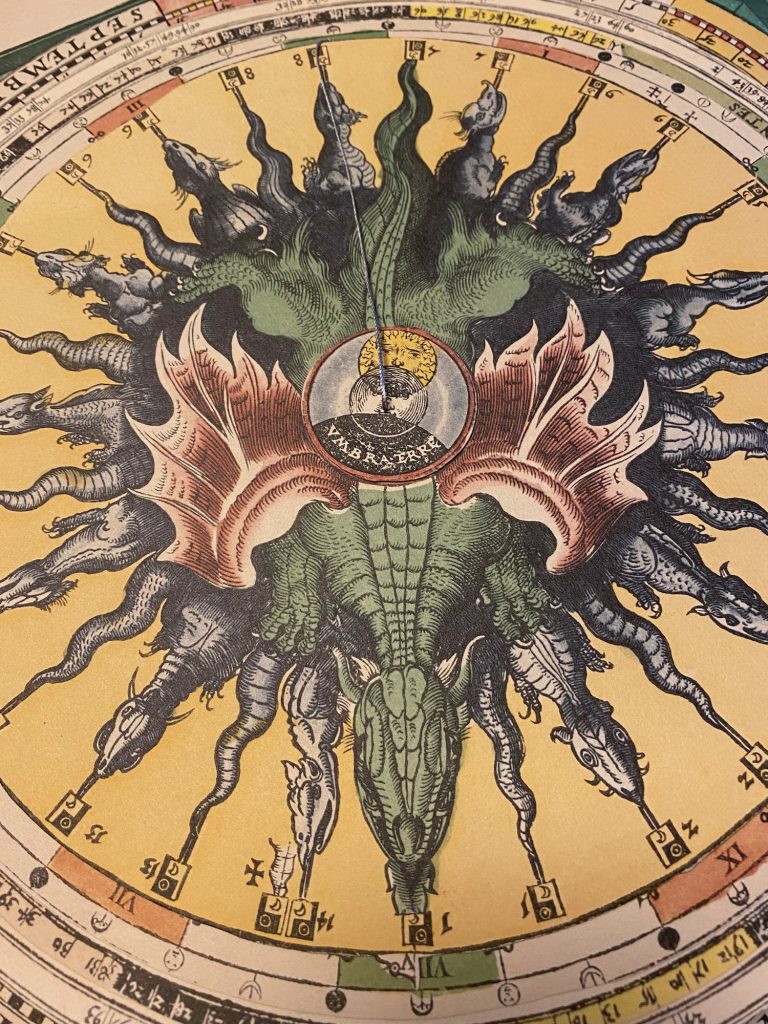

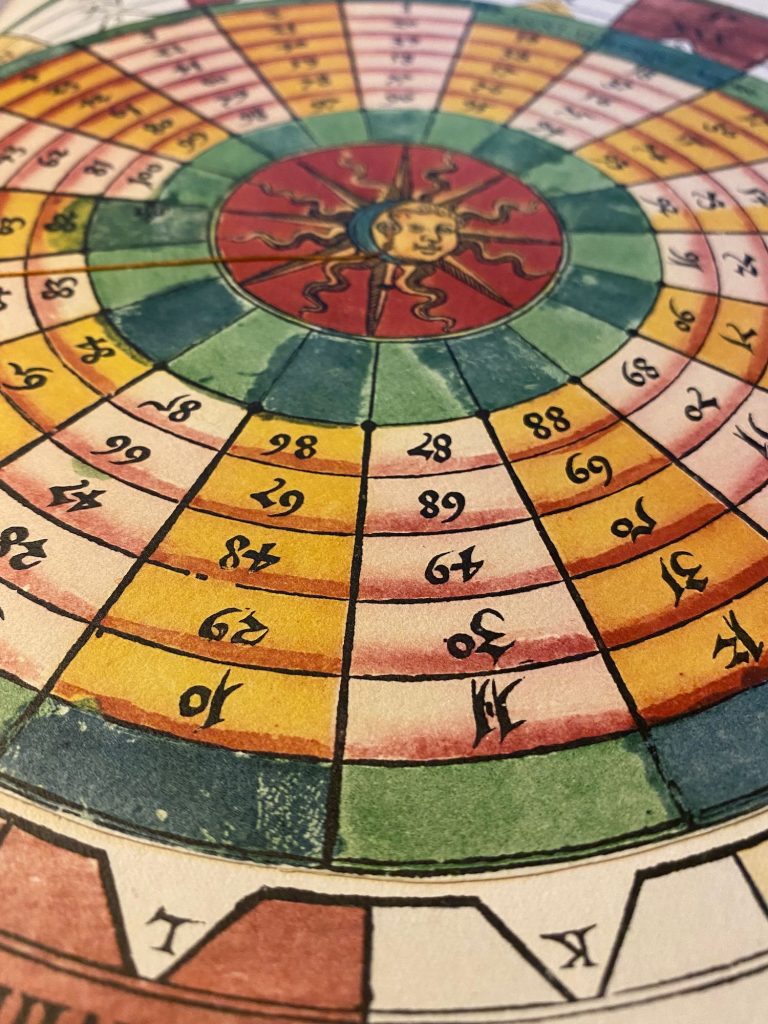

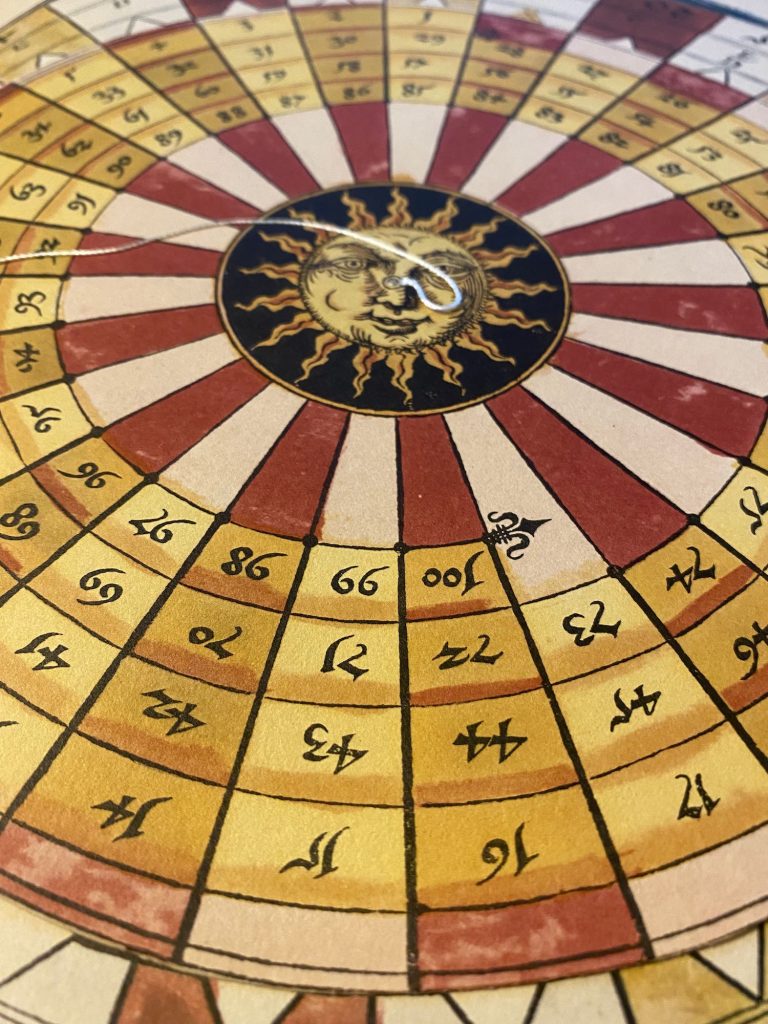

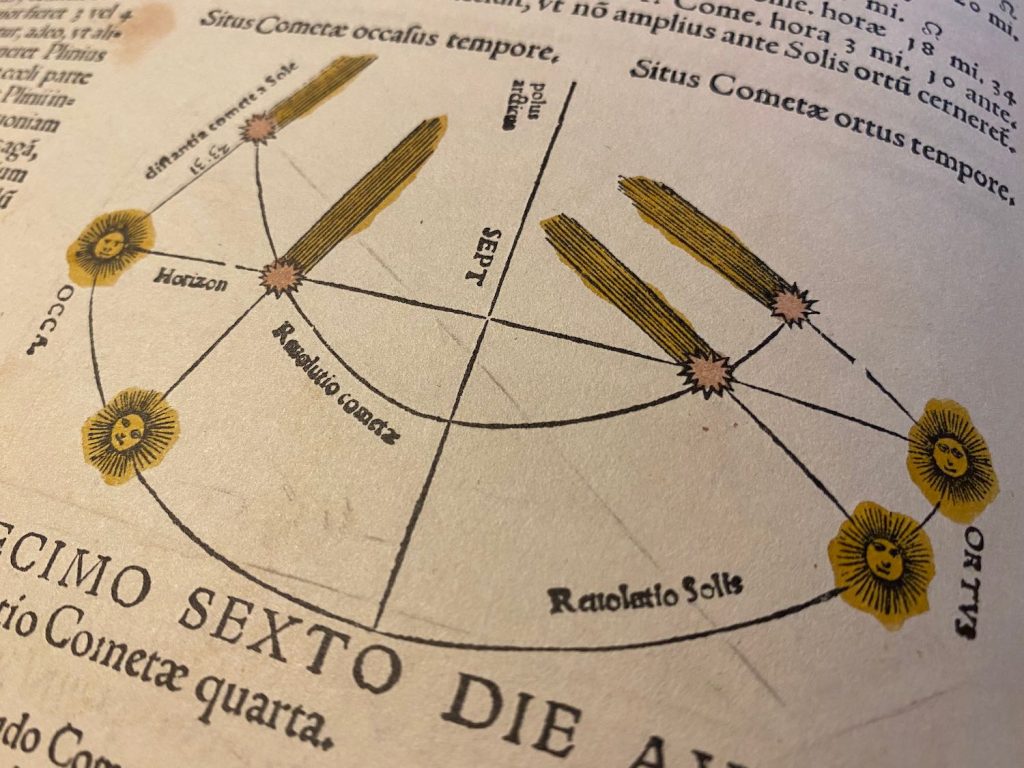

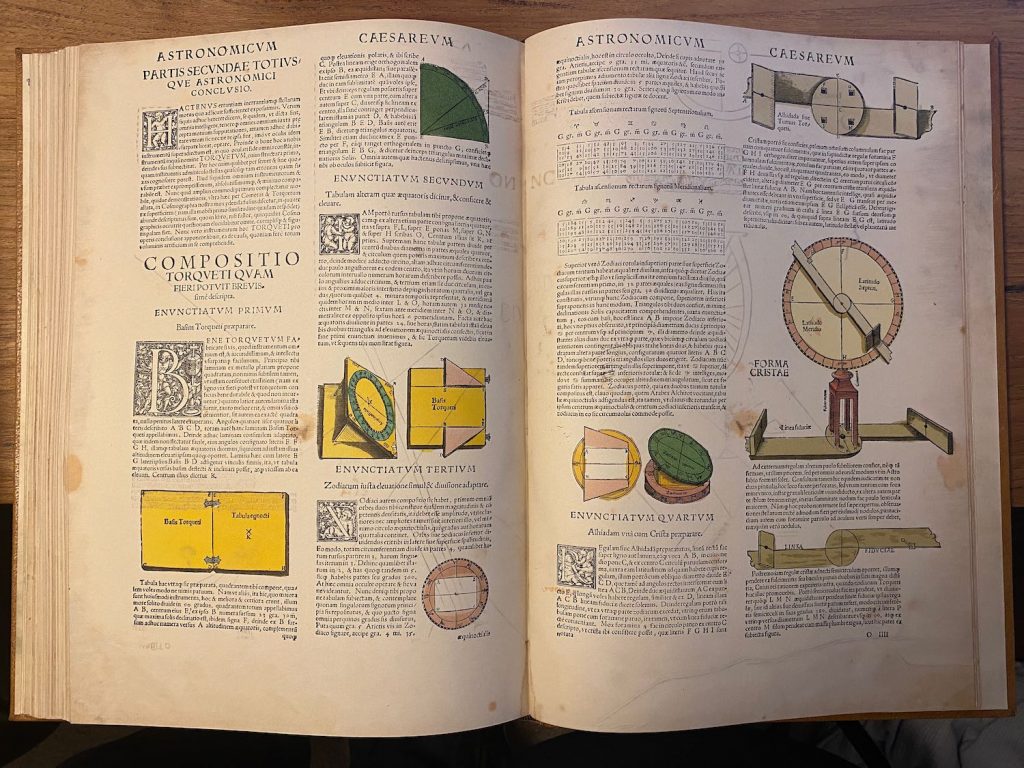

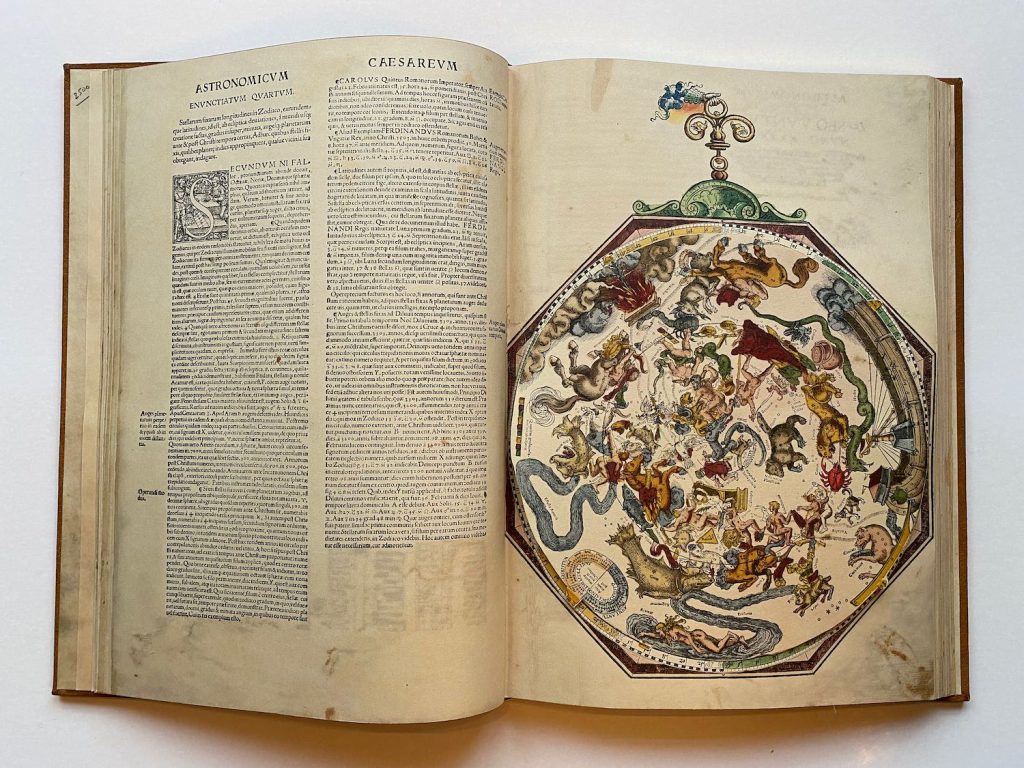

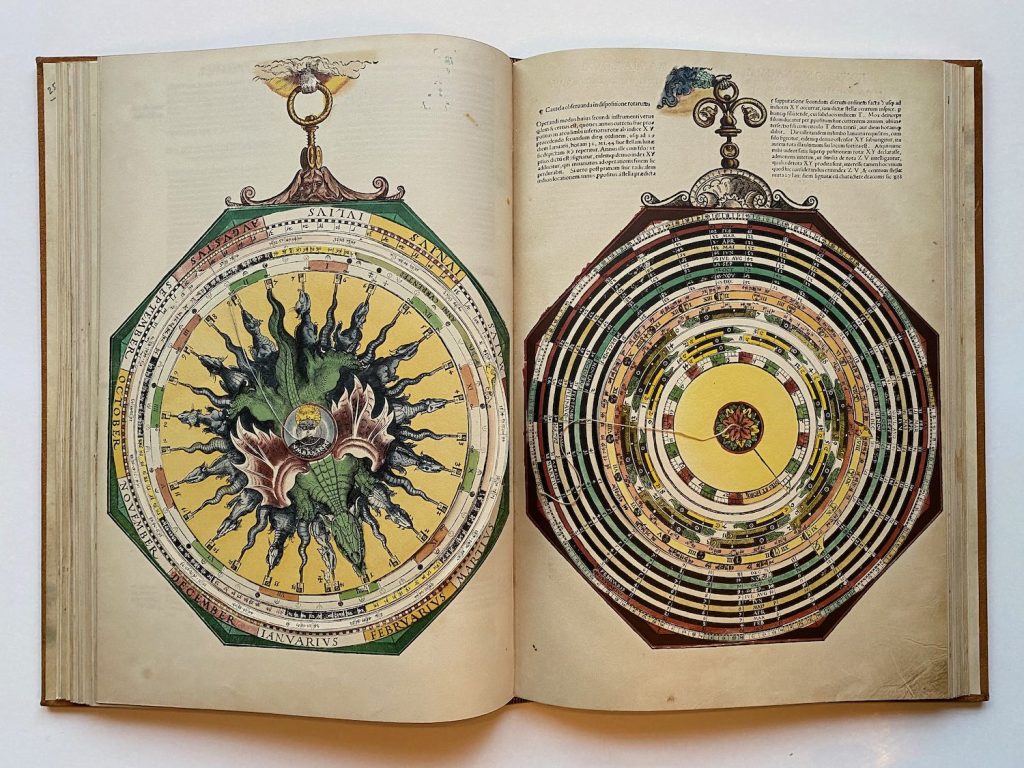

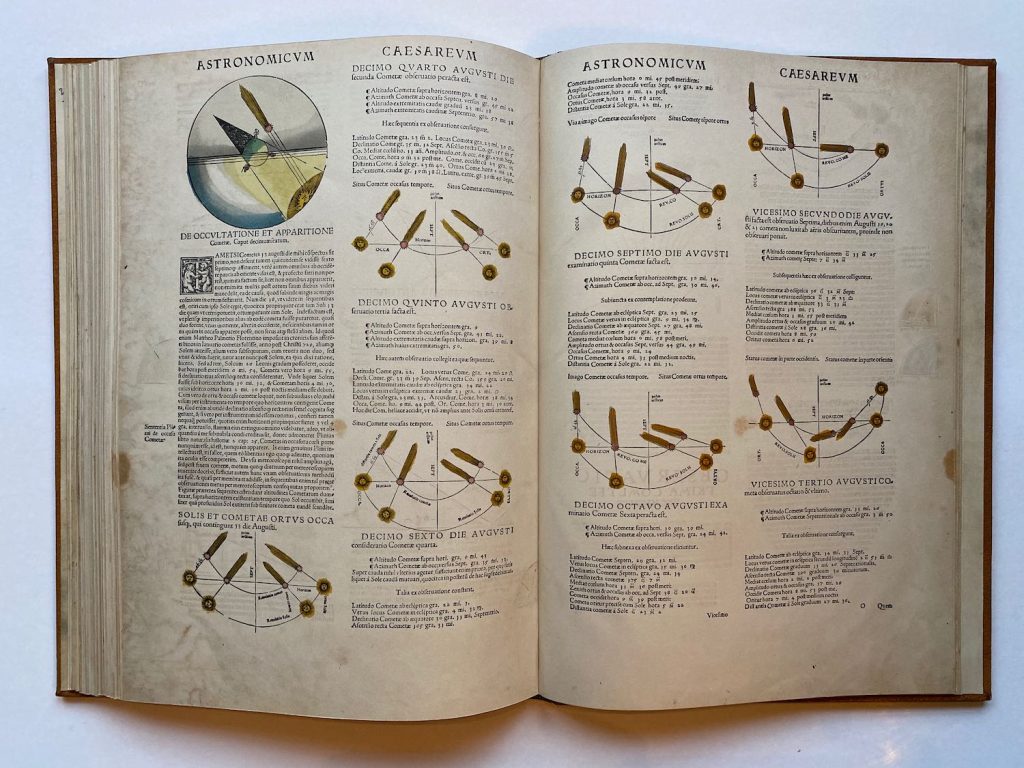

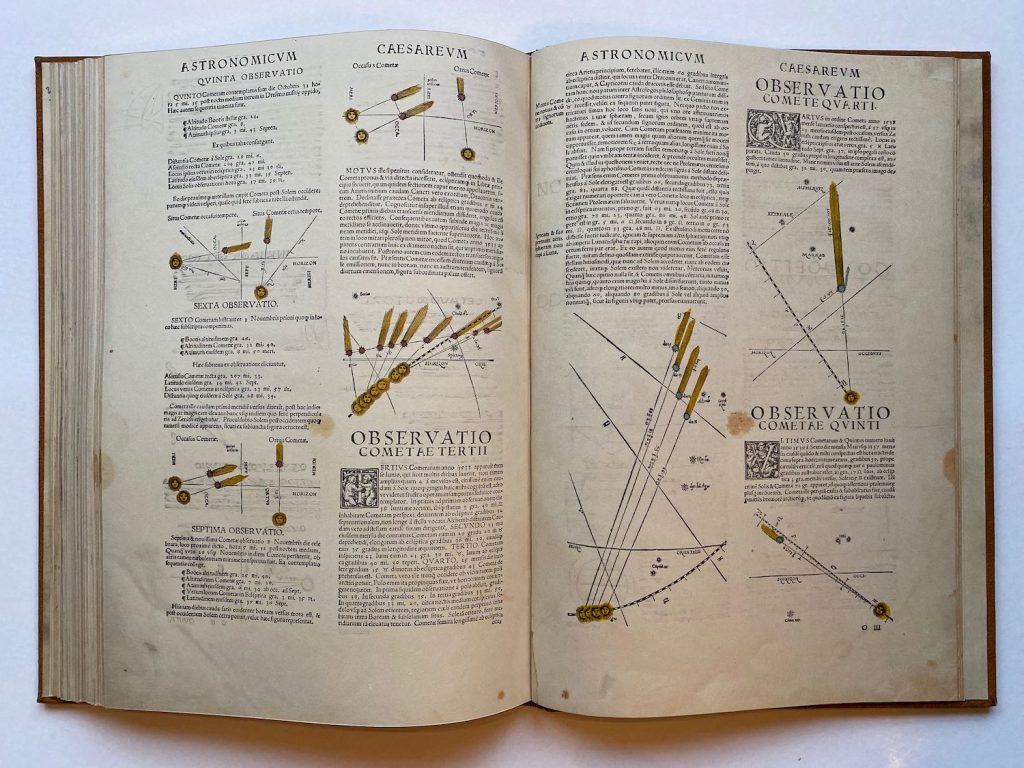

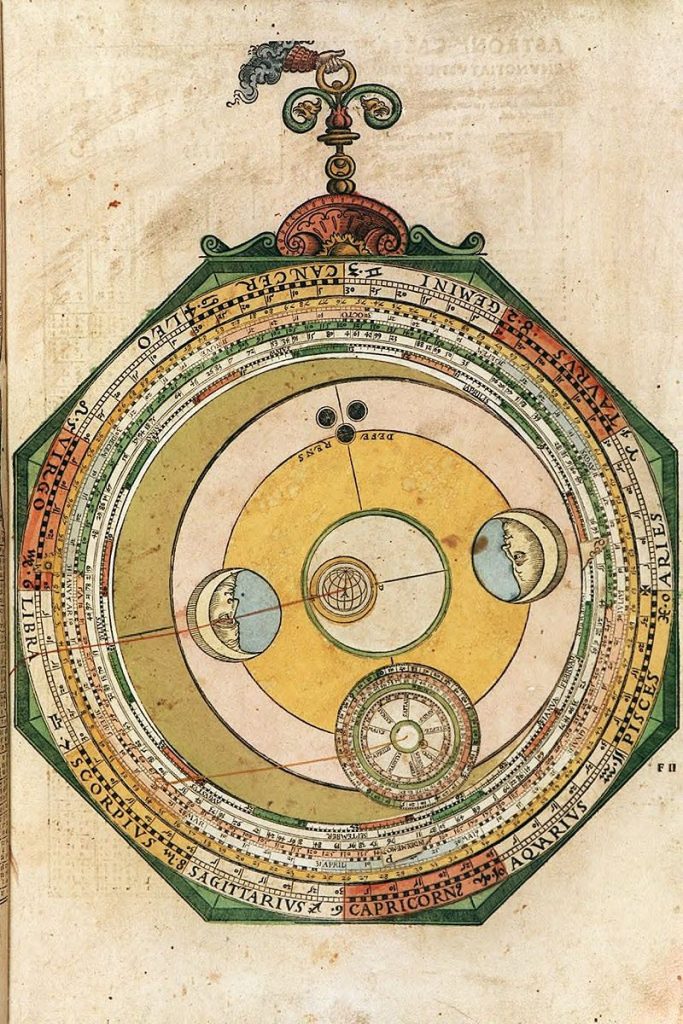

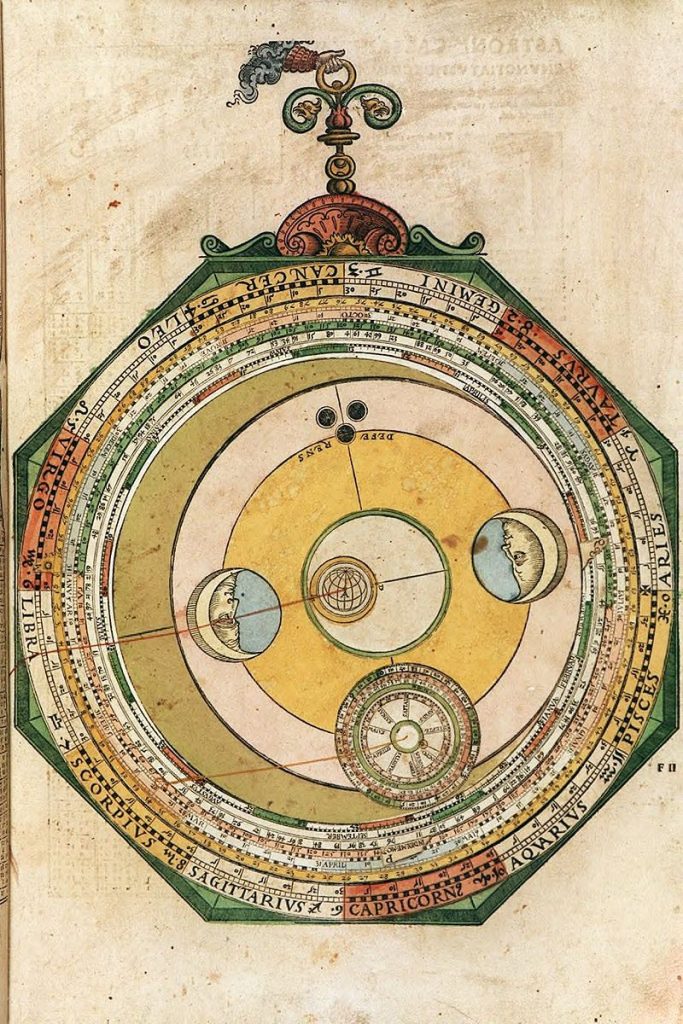

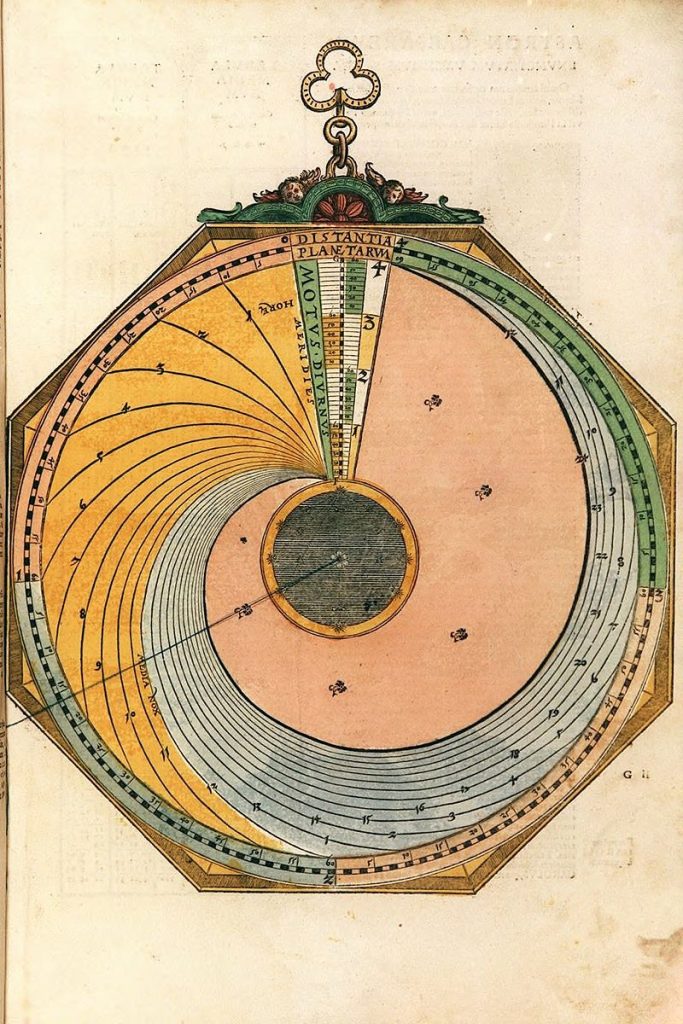

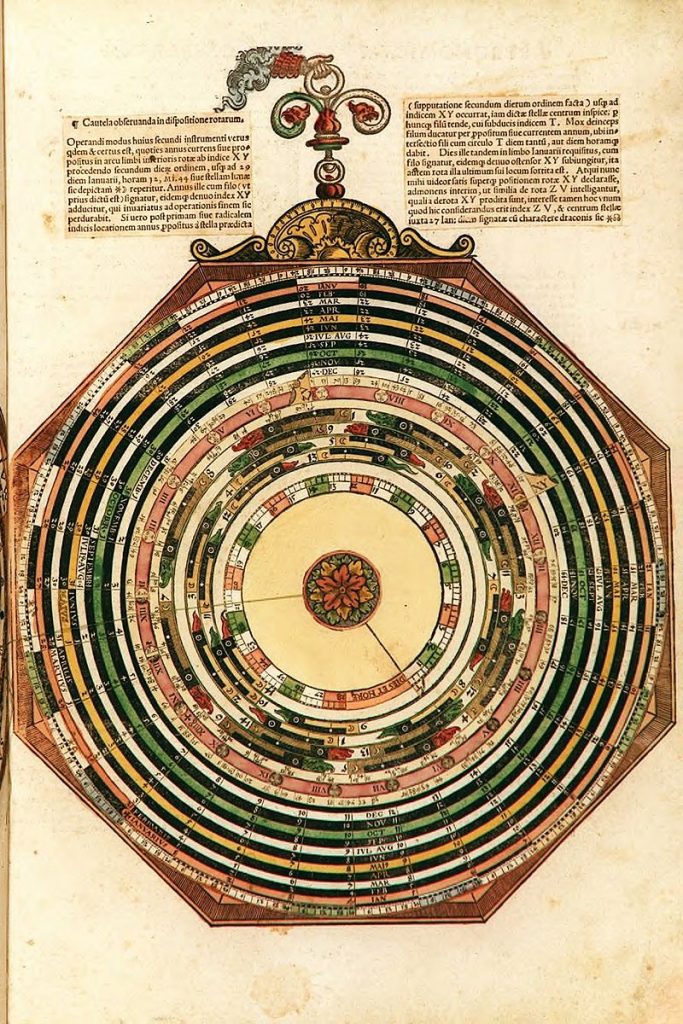

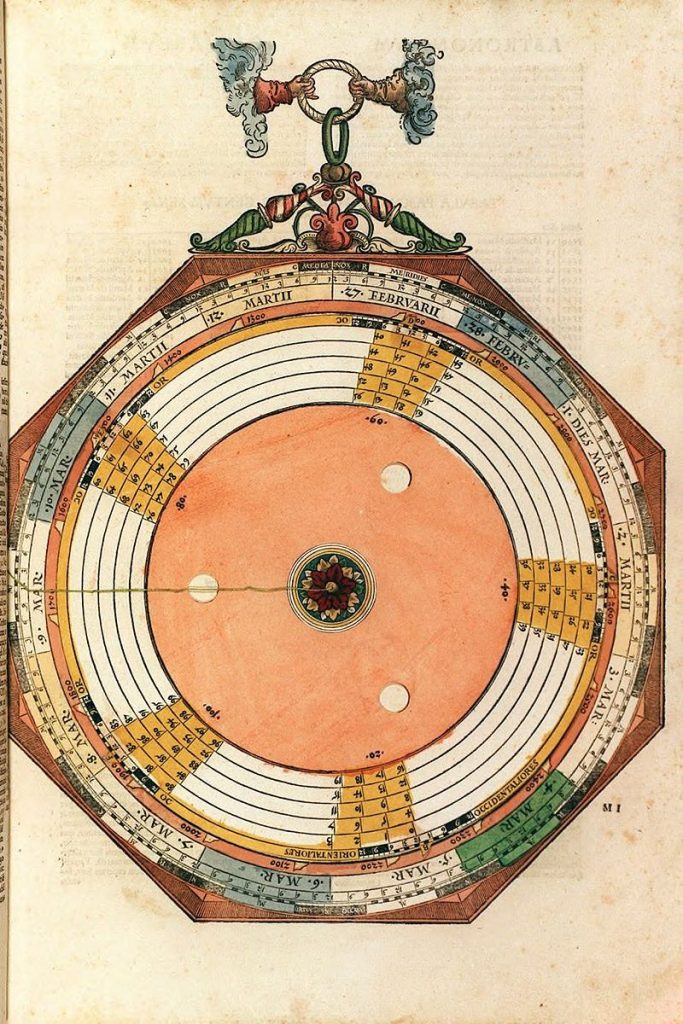

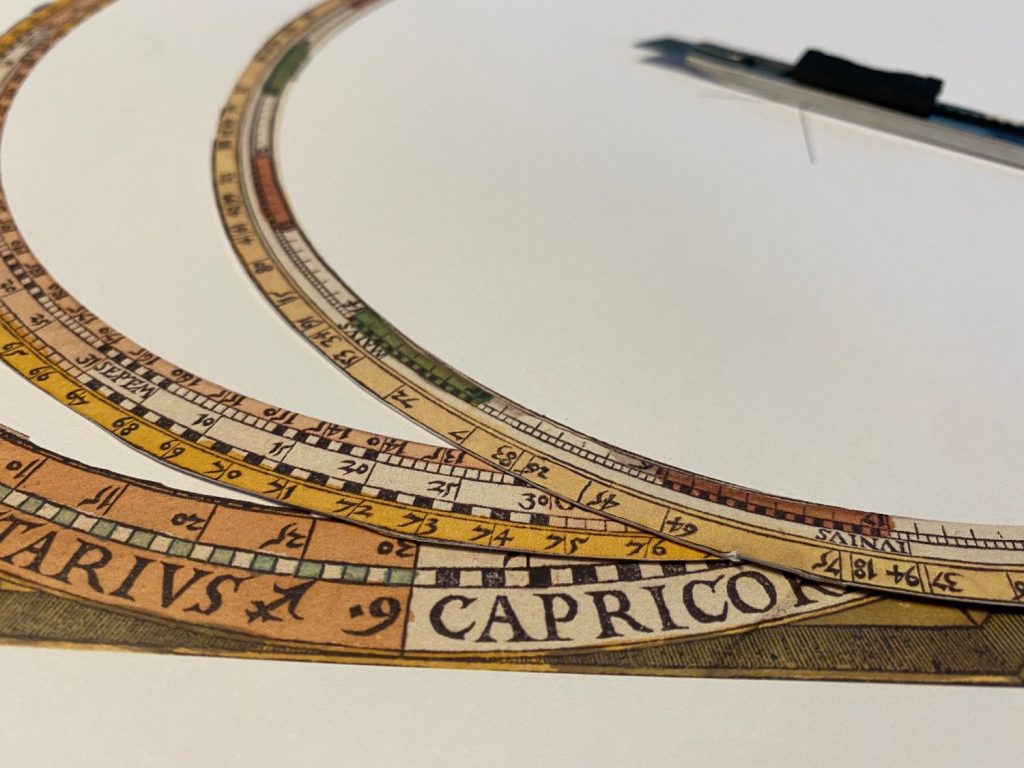

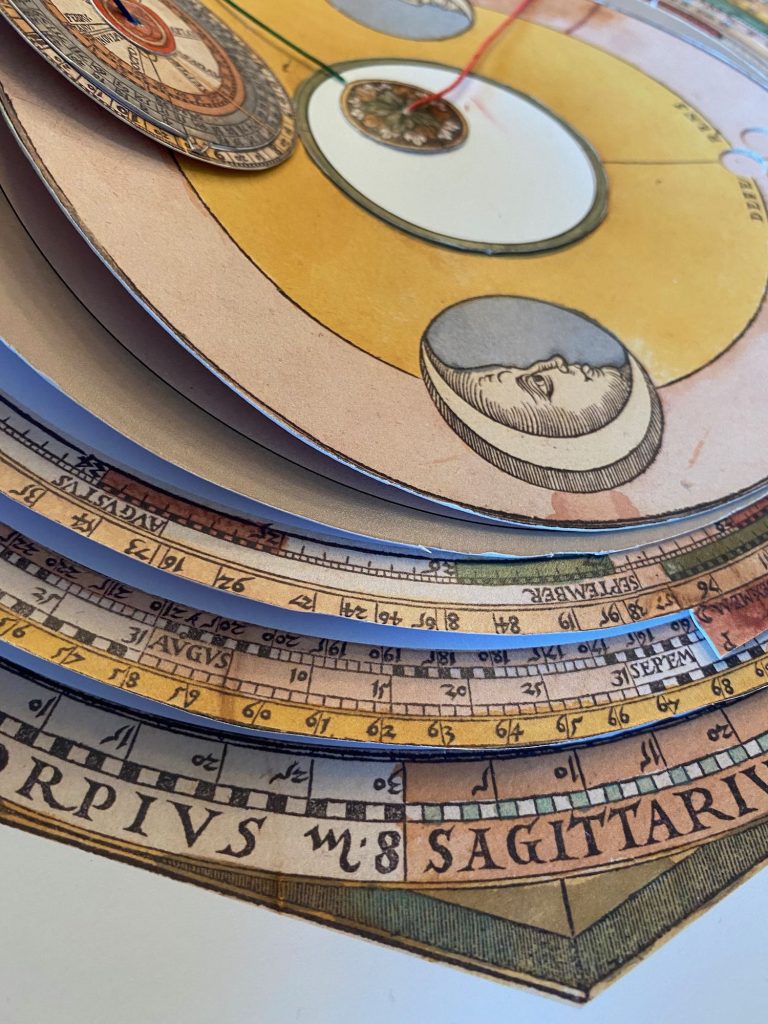

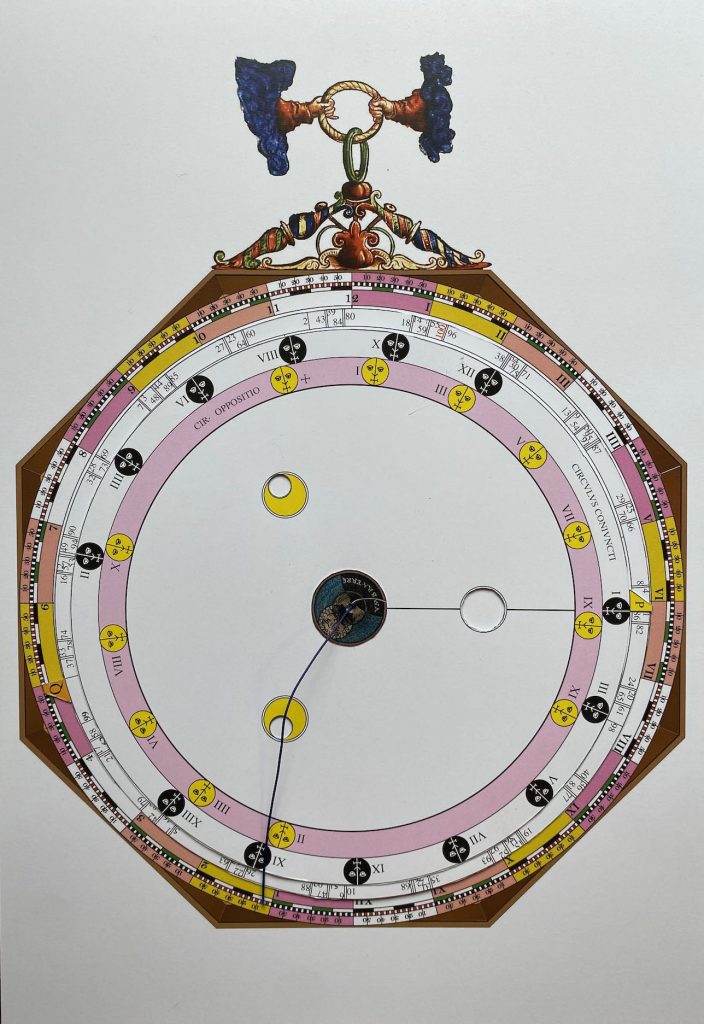

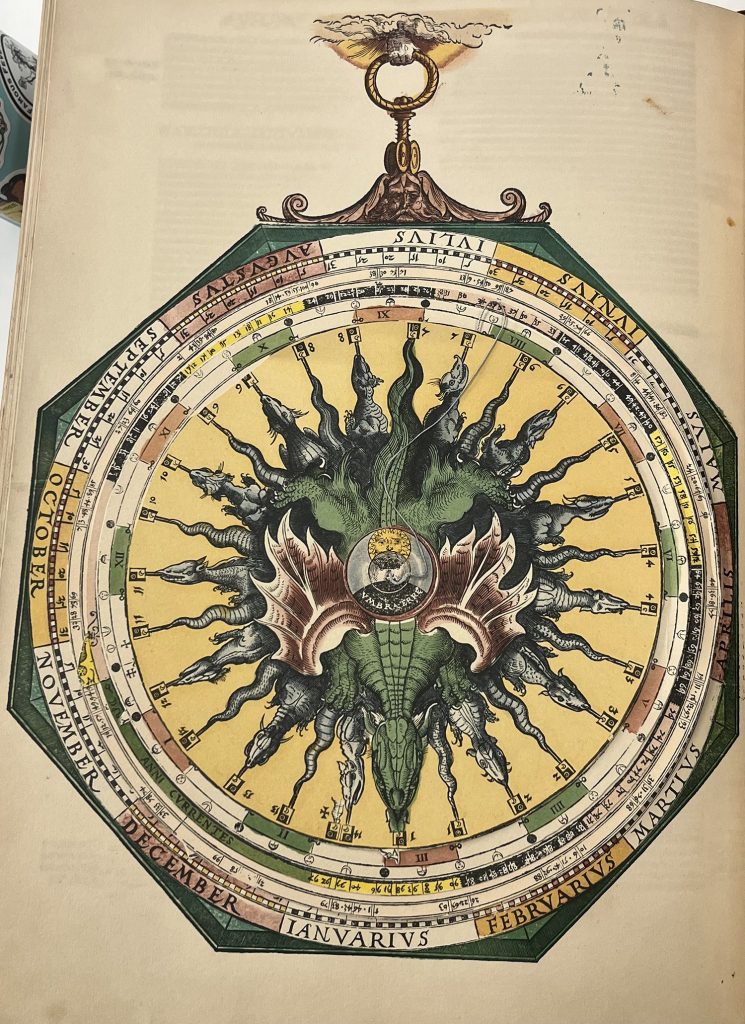

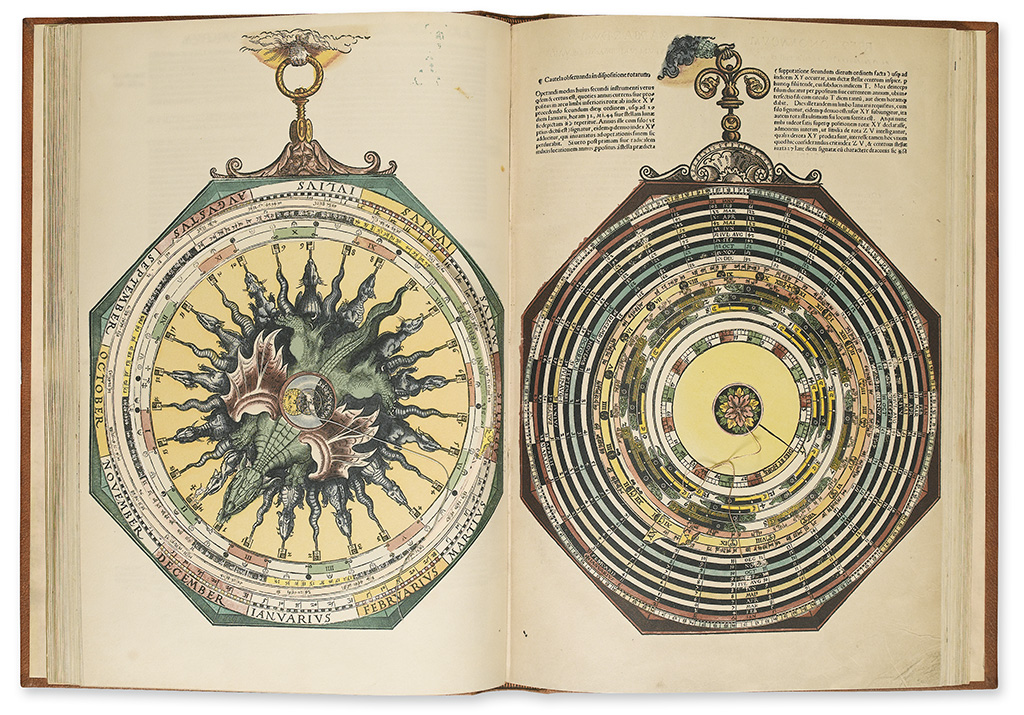

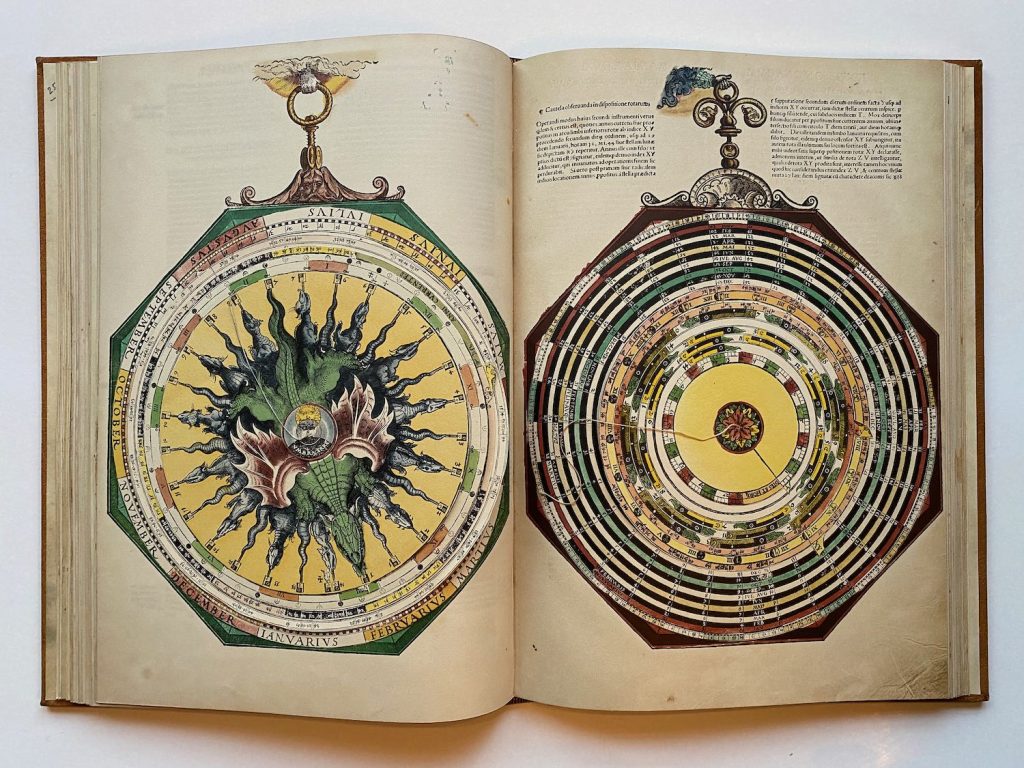

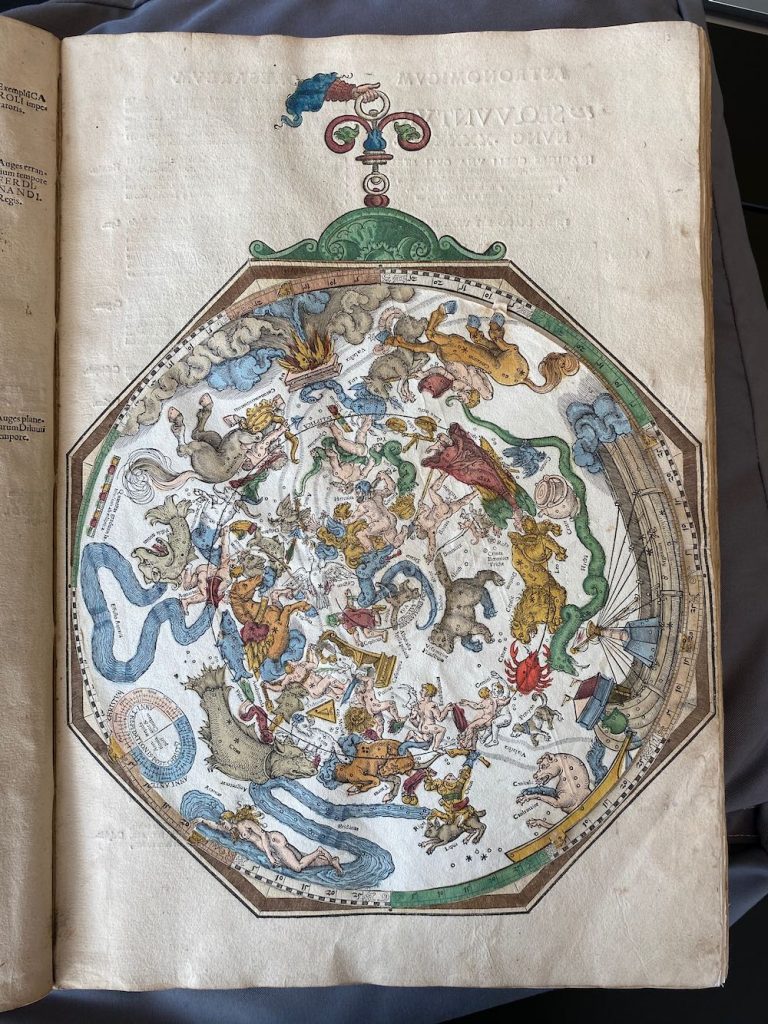

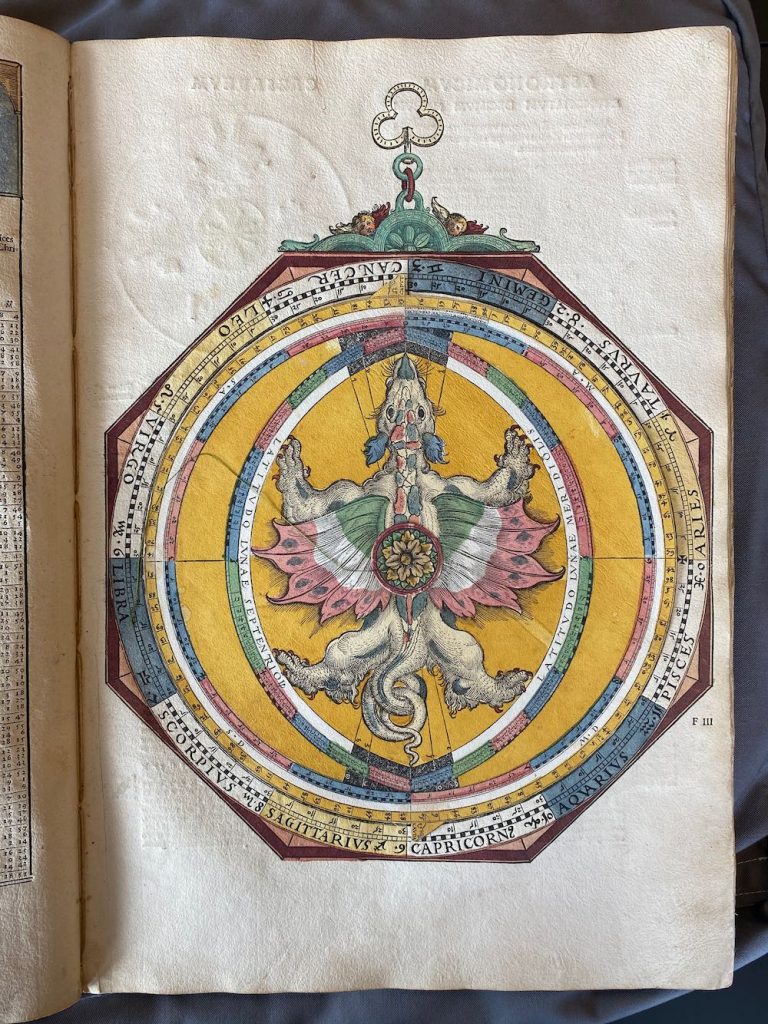

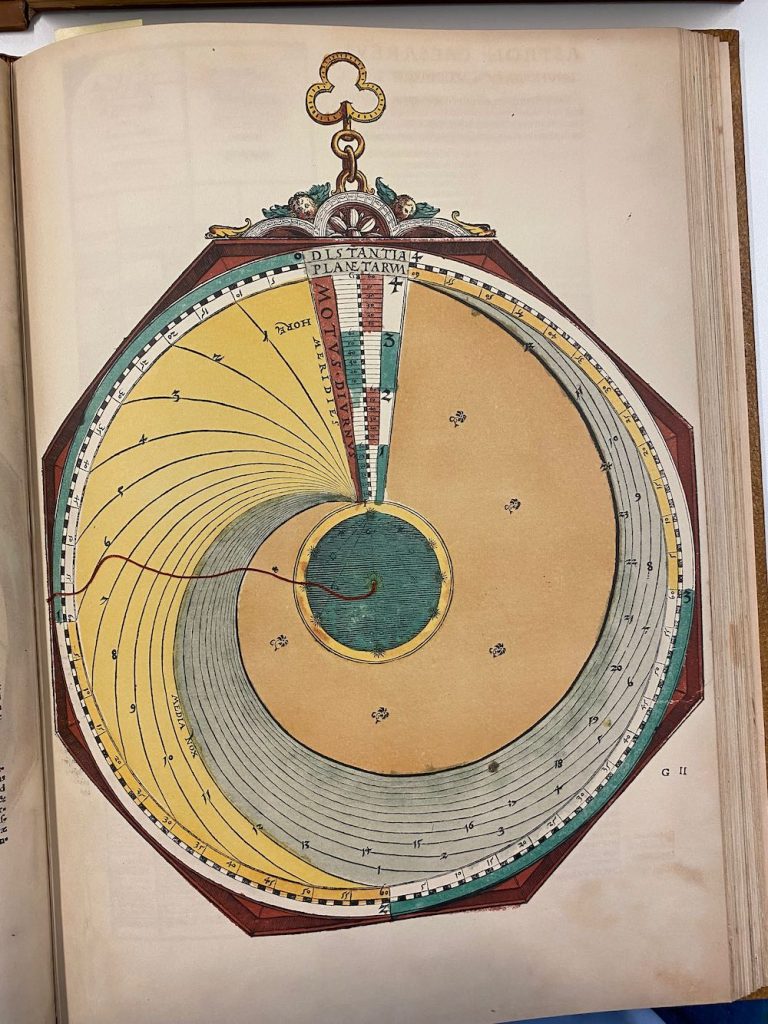

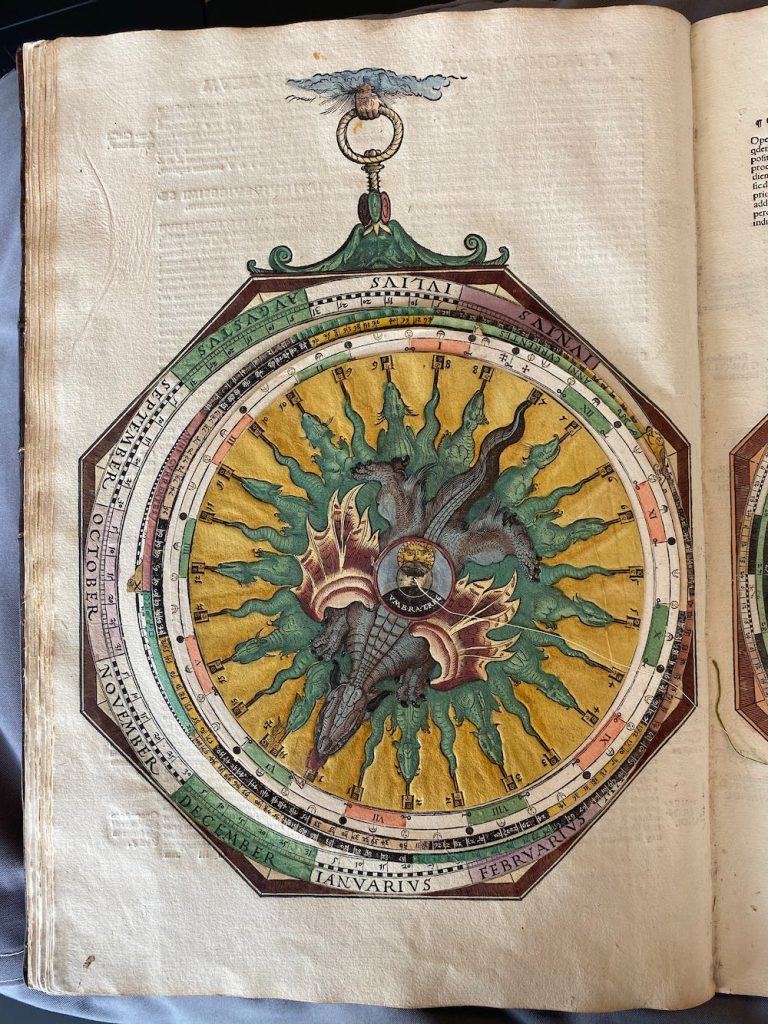

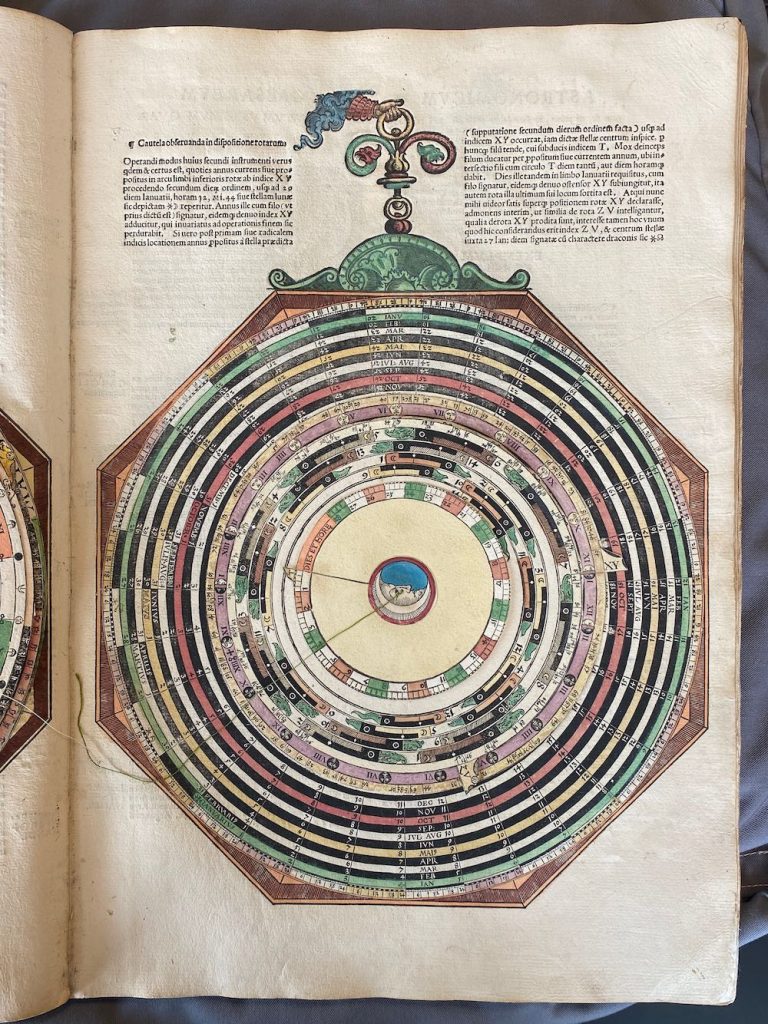

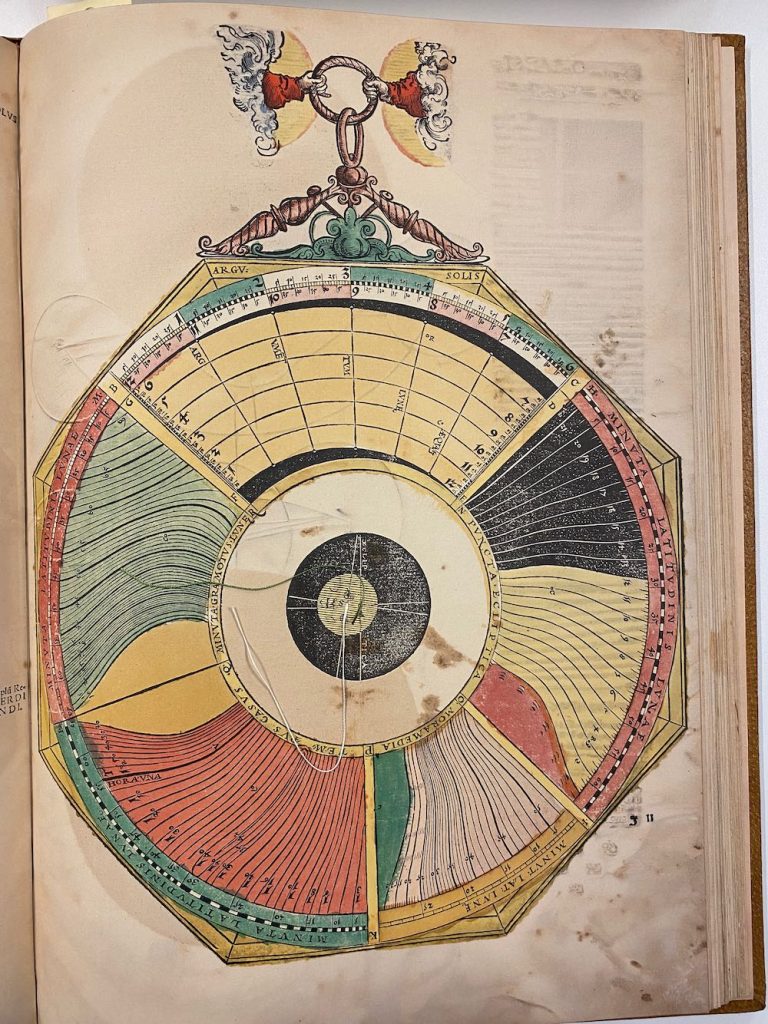

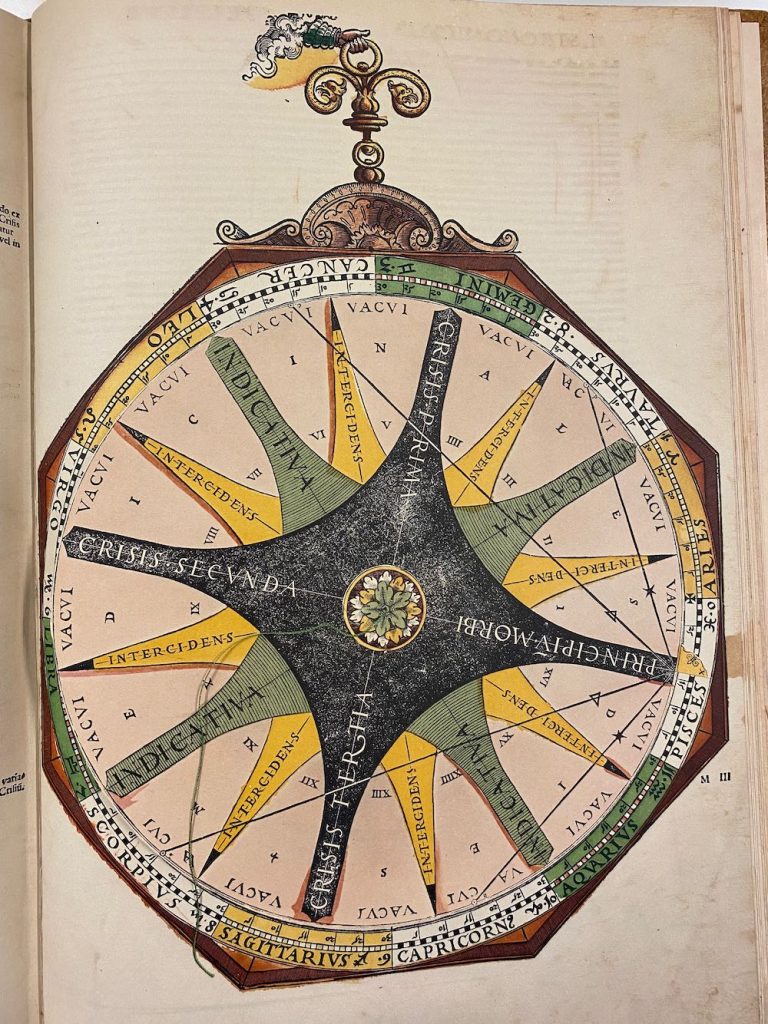

Hij schrijft uitgebreid over de komeet van 1531 (Halley’s comet is deze later genoemd). Hij liet zien dat de staart van de komeet altijd van de zon is afgewend, ofterwijl dat de komeet altijd richting de zon valt (aantrekkingskracht). Hij was een een astronomieprofessor aan de Universiteit van Ingolstadt. Het boek gaat nog wel uit van geocentrisme; een paar jaar later kwam Copernicus met zijn Heliocentristische kijk op ons zonnestelsel. Hij voorspelde zonsverduisteringen, beschreef maar liefst 3 kometen, maar gebruikte het boek ook om horoscopen uit te trekken: astrologie in plaats van astronomie…. De papieren computers (schijven op elkaar waarmee berekeningen zijn te maken) worden volvelles genoemd en werden in de 13e eeuw al toegepast. Apianus was er goed in en paste ze toe in meerdere boeken, waaronder zijn eerdere Cosmographia. In dit boek zitten er 21. Het is een groot (Folio formaat) dik boek: 45.8 × 32.6 × 5.2 cm. In feite is het een instrument (astrolabe) in de vorm van een boek.> Het blijkt mijn 200e astronomieboek te zijn, maar da’s puur toeval… Sommigen 20 en 50 cent bij de Sterrenwacht, deze iets duurder.

Een snelle video introductie

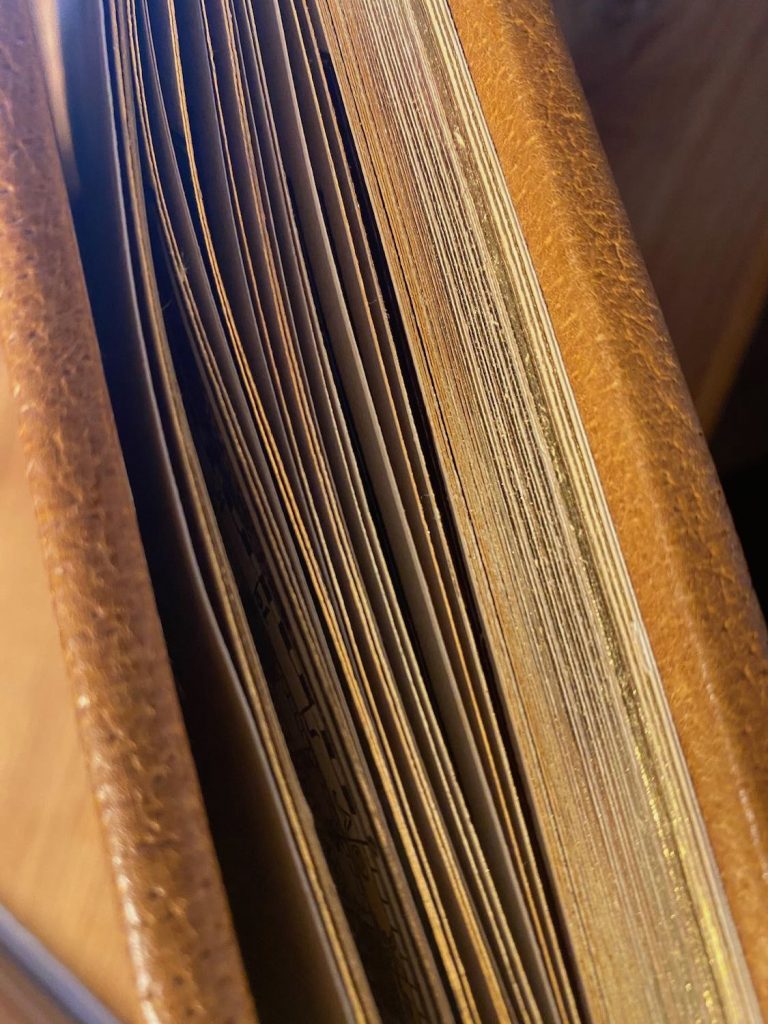

Nog meer detailfoto’s van het boek, maar nu van mijn boek 😉

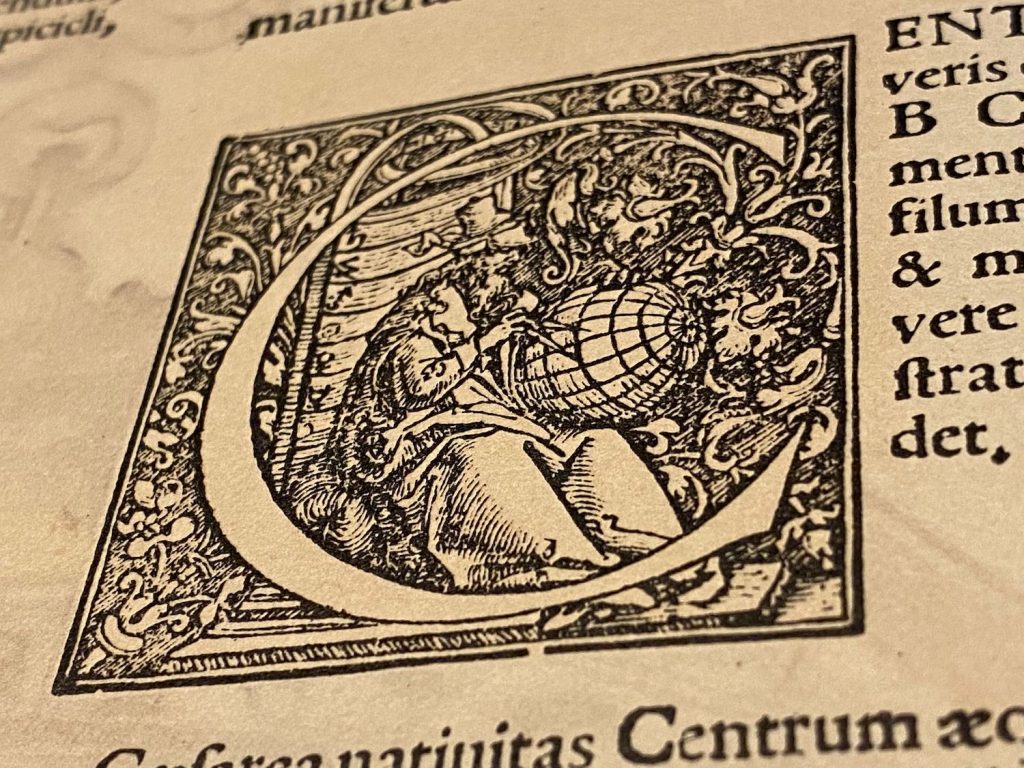

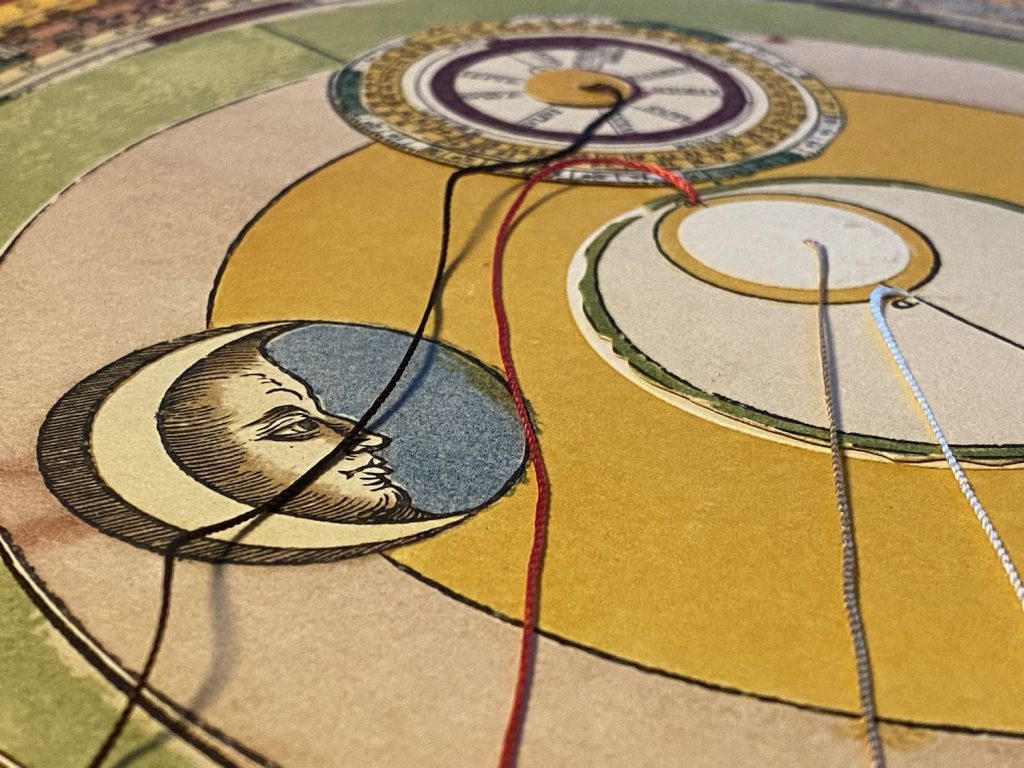

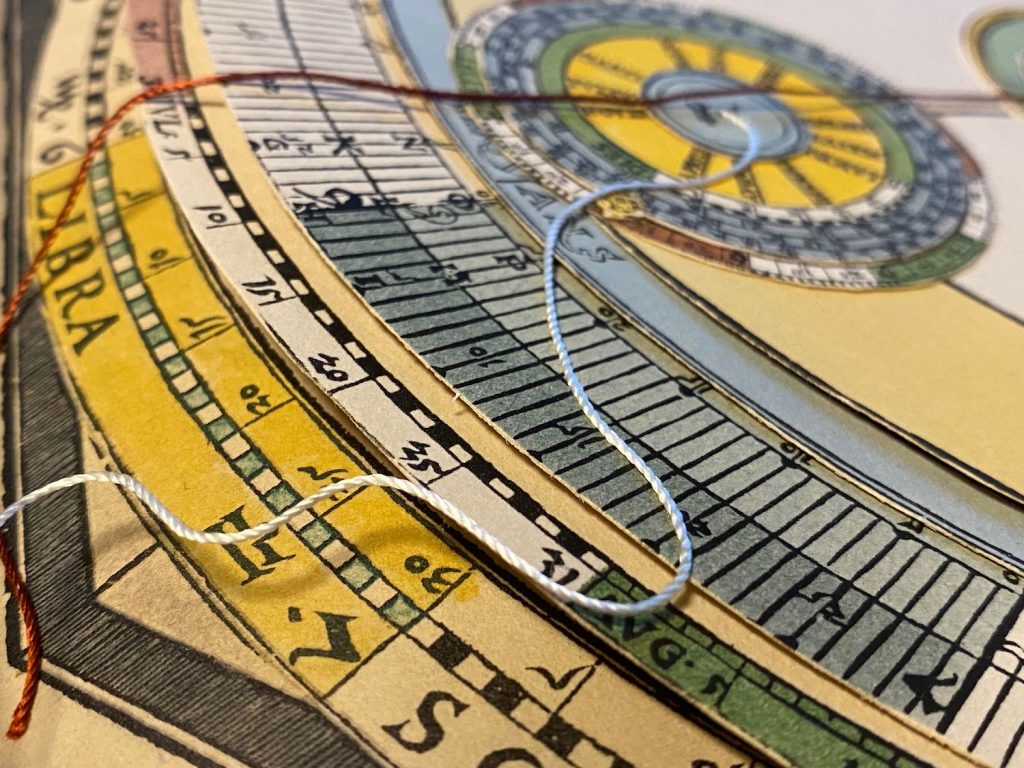

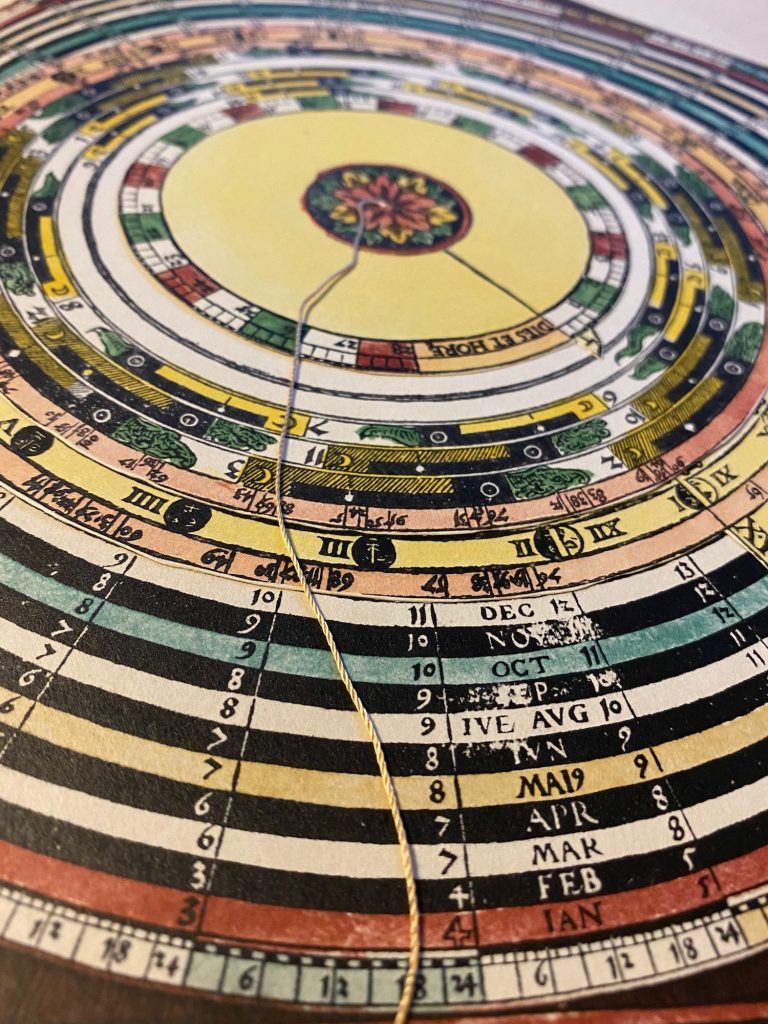

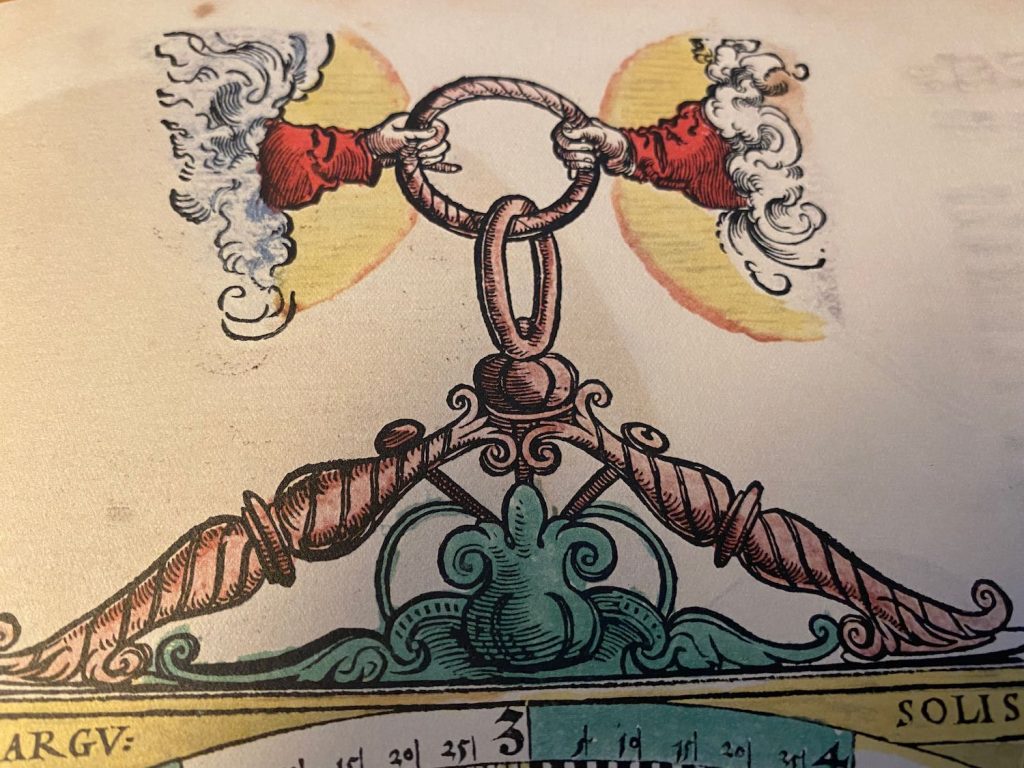

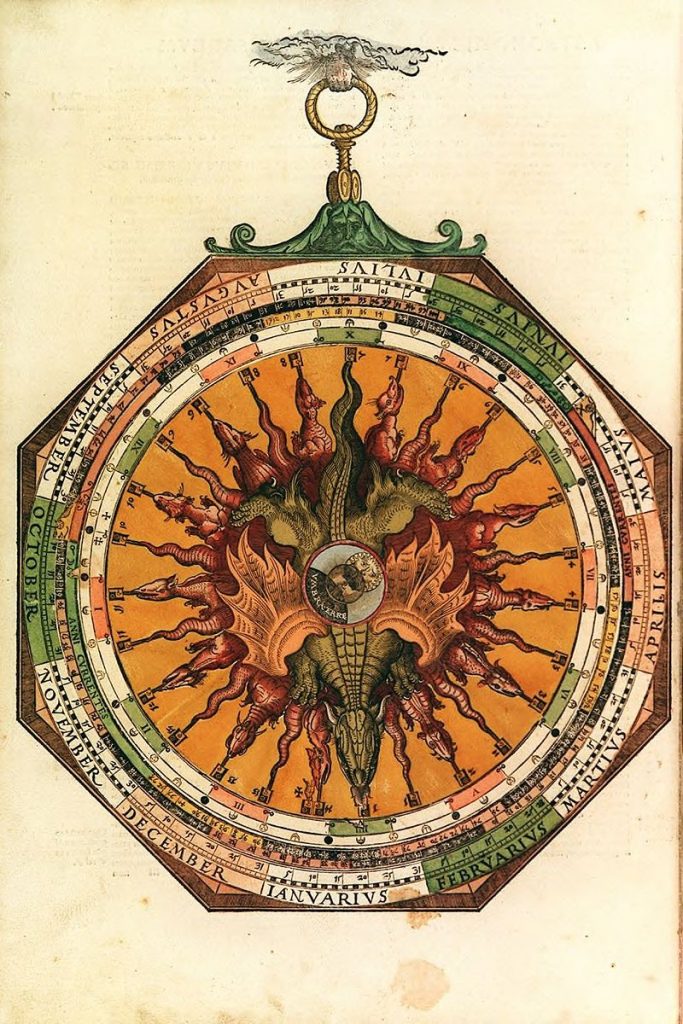

Ik heb al veel foto’s van 3 van deze boeken die ik heb ingezien, maar het blijft mooi, dus hier foto’s uit mijn eigen boek. Zie de mooie snedevergulding, gouden initialen, de touwtjes om calculaties mee te maken, de gelaagde ‘rekenmachines’ met soms wel 6 lagen, de prachtige draken en nog veel meer…:

Kijk voor veel meer informatie en foto’s naar de post van het origineel uit 1540 of van een broertje van dit boek, nummer 332.

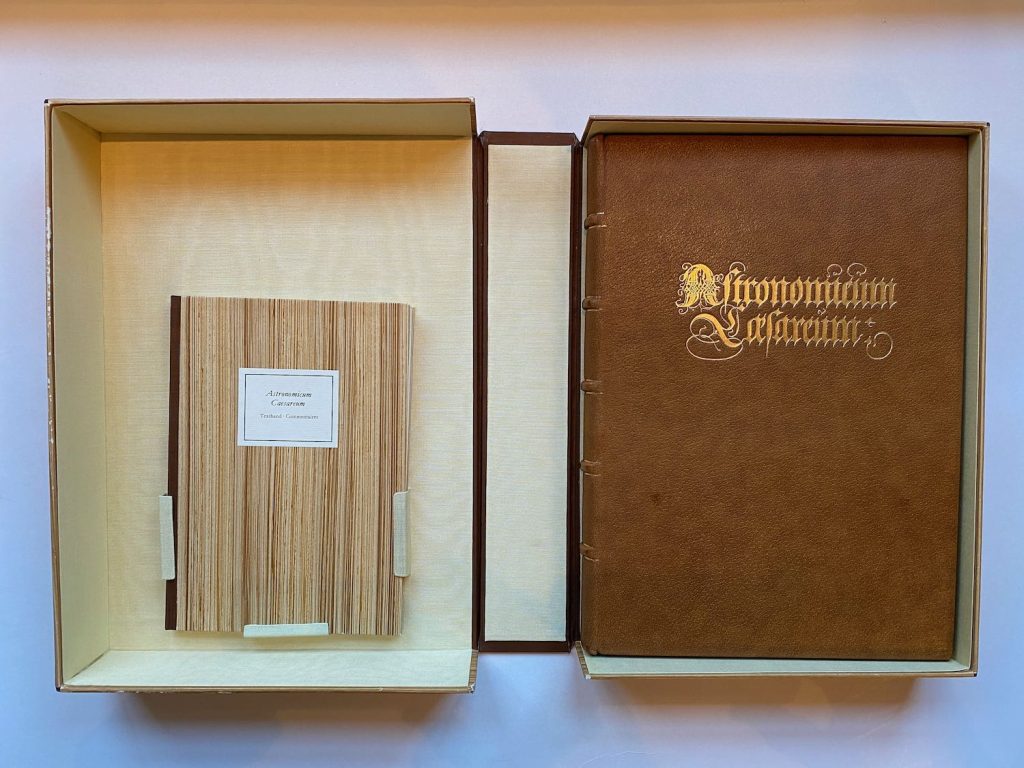

De verpakking vanuit de uitgeverij ‘Edition Leipzich’

Volgens Owen Gingerich (die 111 originelen bekeek, waar hij 25 jaar over deed!) heeft de uitgever in 1967 onnodige fouten gemaakt: De gebruikshandleiding van Apianus werd wel meegenomen in de facsimile, maar niet gelezen. Ook werd de originele versie die vlakbij beschikbaar was in de bibliotheek van Leipzig niet geraadpleegd. Basis was een vervallen origineel van de bibliotheek van Gotha in het midden van Duitsland.

Het begeleidende boekwerkje

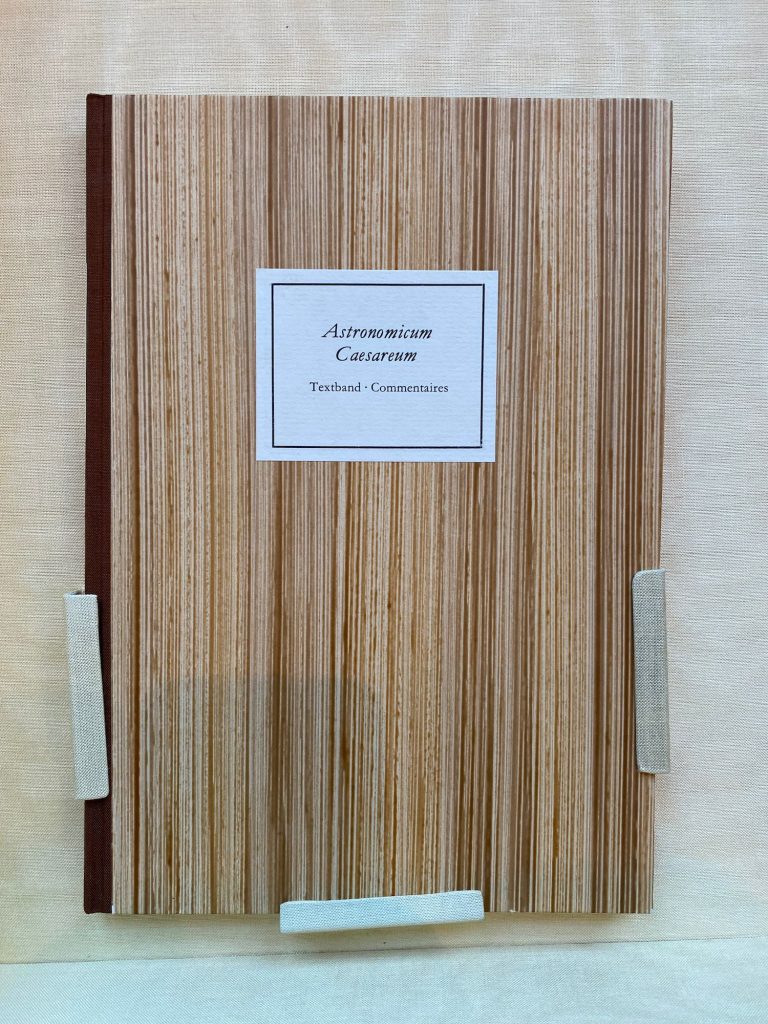

In de grote doos waarin het boek aangeboden werd zit ook een mooi begeleidend boekje. Achtergrond informatie in Duits en Frans (?) en ook een eenvoudige facsimile van het begeleidende boekje dat Apianus toen bijleverde, ook in het Duits.

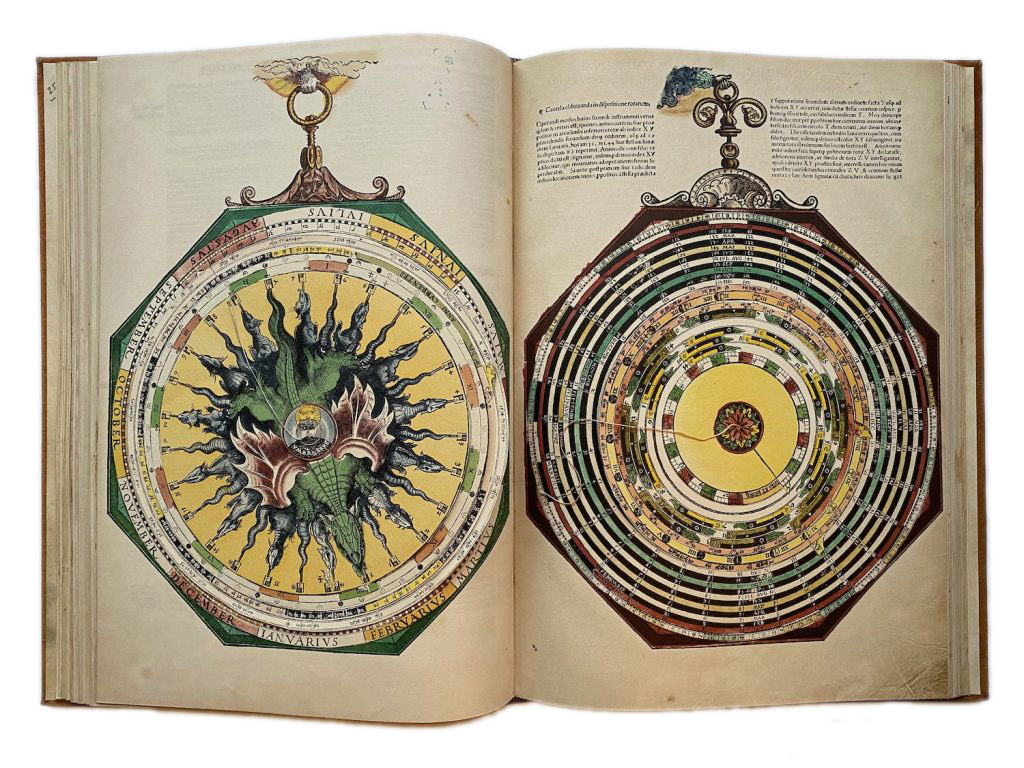

Dubbele pagina’s / Spreads

Enkele fouten in deze facsimile uitgave

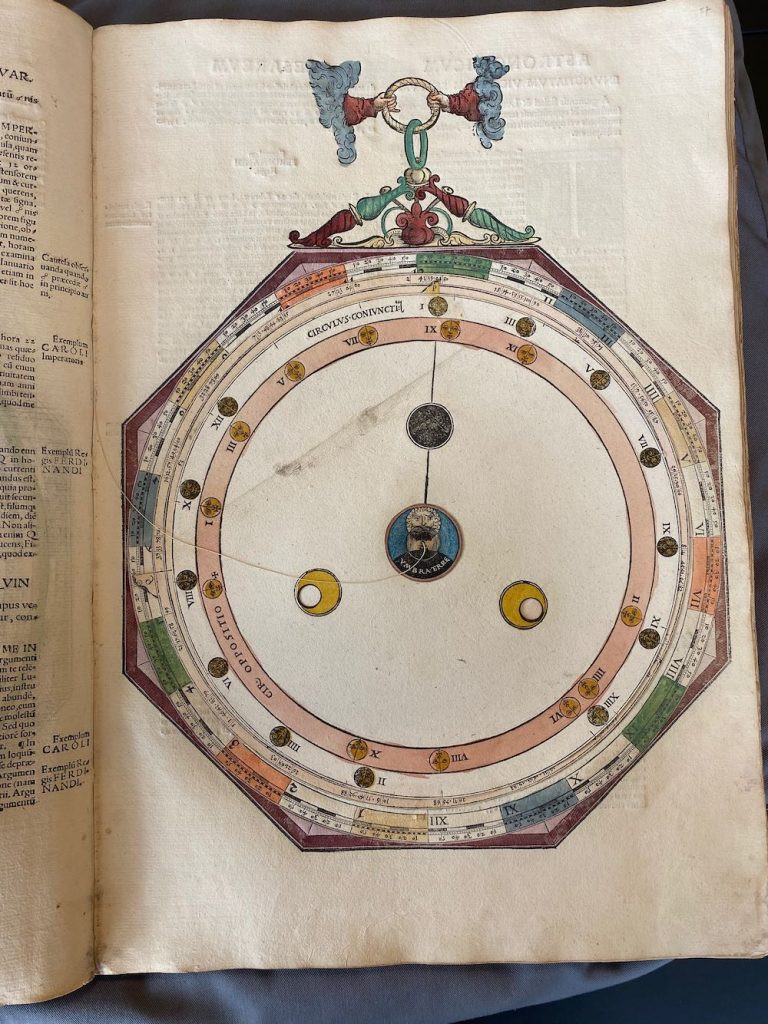

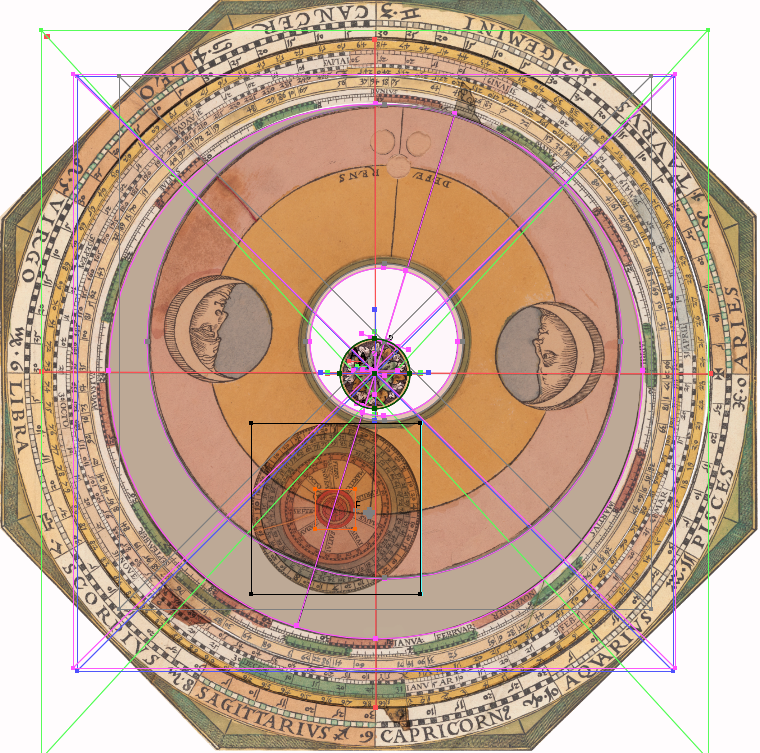

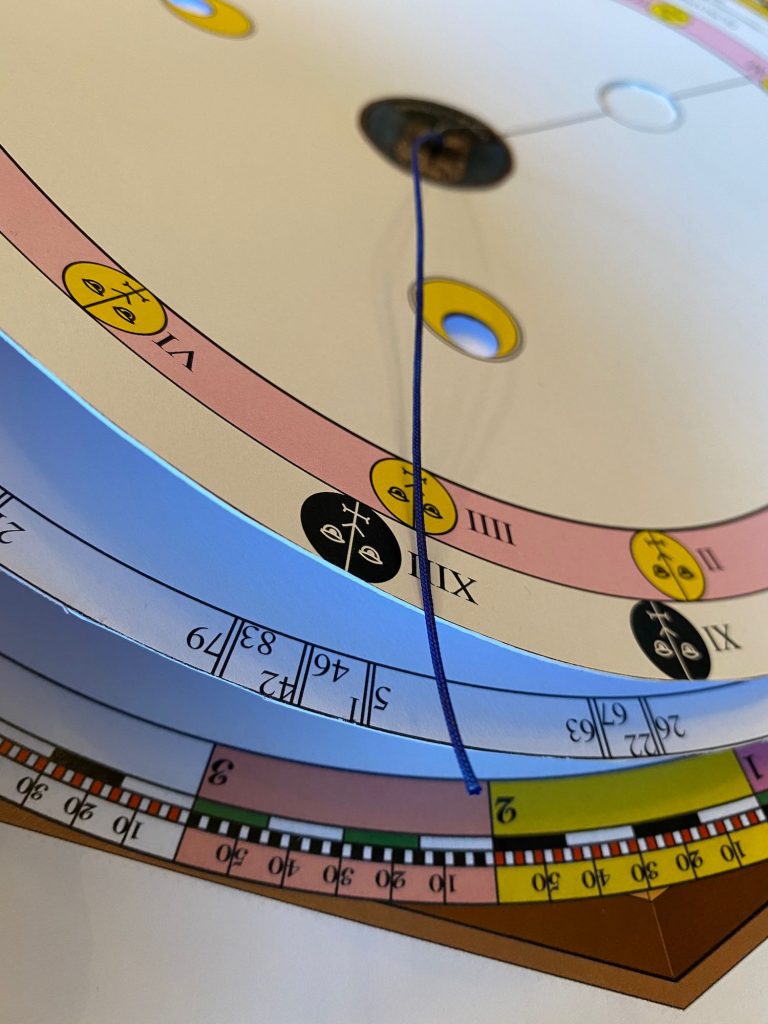

Een van de fouten in de facsimile is Volvelle 21. Bij het maken van het boek hebben ze 3 stuks niet goed uitelkaargehaald en / of terug in elkaar gezet: Nummer, 2, 14 en 21. In de Facsimile heeft nummer 21 een achtergrond (Mater) die verder totaal onbekend is en verder niet in het origineel voorkomt, dachten we… Hij zit er wel, maar Apianus heeft hier gewoon een eerder plan aangepast en de reeds gedrukte vellen hergebruikt: door de schijven erop te leggen valt het niet op dat hij de achtergrond hergebruikt. Lars Gislen dacht al dat het zoiets moest zijn, maar omdat ik zelf het origineel niet meer vast mag houden (niemand overigens, zonder toestemming van de Curator) waren we afhankelijk van de medewerking van de Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden: even geduld bewaren, maar Nicolien heeft ons enorm geholpen: onder de schijven van Volvelle 21 zit inderdaad de ‘hergebruikte misdruk’ mooi verstopt. In mijn facsimile is dat gewoon Volvelle 21, zonder verdere schijven. Zie verder in dit blog hoe we dat allemaal uitgezocht hebben en zelfs de Volvelles opnieuw hebben gecreëerd om toch een compleet correcte set te hebben…

Linksboven het origineel uit Leiden. Rechts Volvelle 21 uit mijn facsimile…

Ik heb veel contact met Lars Gislen van de Lund Universiteit. Zijn interesse ontstond toen ik een pagina in mijn facsimile heb, die hij niet herkende uit zijn uitgebreide onderzoek. Hij is speciaal naar de Universiteit gegaan om een artikel van super-kenner Owen Gingerich op te zoeken. Hij heeft het voor me gescand. Het artikel komt uit 1971 en is dus van enkele jaren na het uitkomen van dit boek. Voordat hij het artikel had gevonden had hij zelf al uitgevonden waar de fouten zitten: het artikel bevestigde dit nog, maar de zoektocht is nog niet helemaal afgerond…

Daar waar er fouten zijn, plaats ik steeds een A versie (Het origineel) en een B versie (alle facsimiles, waaronder ook de mijne). Het betreft nummers 2, 14 en 21 (met deze laatste is de gezamenlijke zoektocht begonnen.)

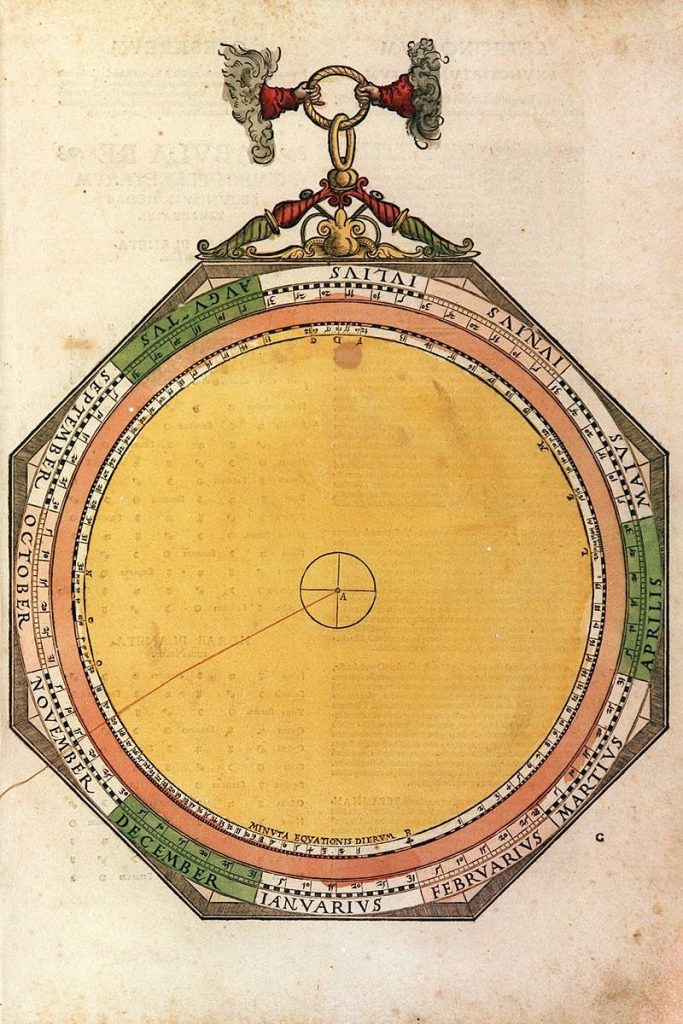

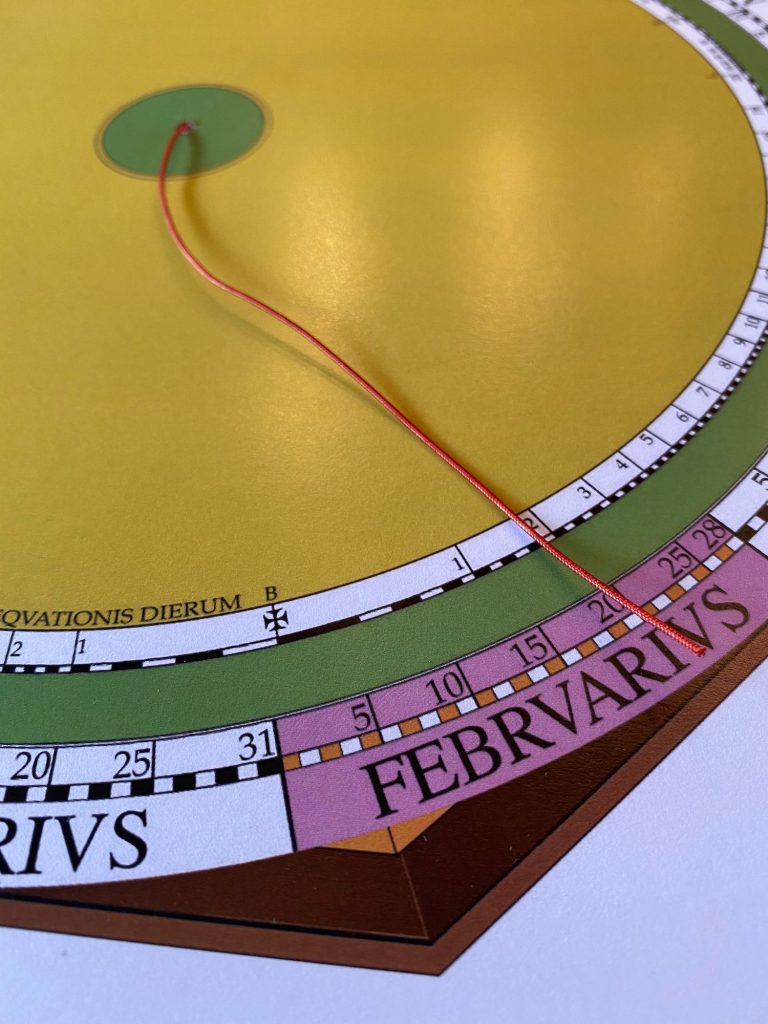

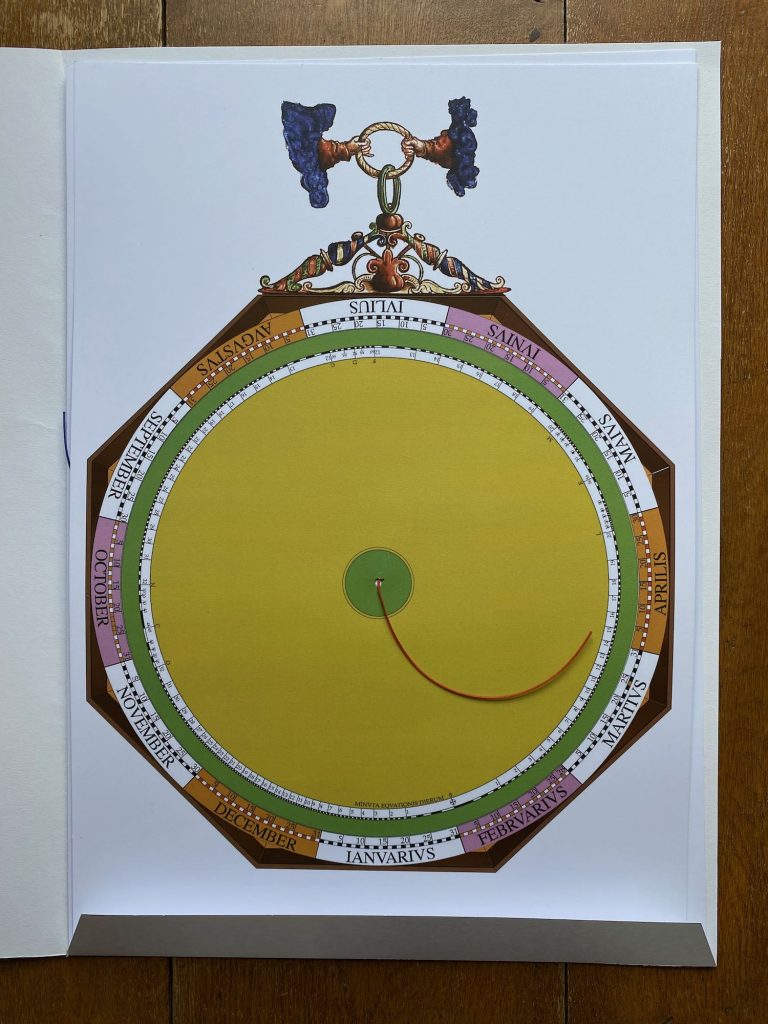

From Lars: All the volvelles in AC are made in the same way. On the page itself a background is printed, what I call a MATER. Then, on top of that, on SOME of the volvelles one or more disk layers are stacked and fixed by threads. Many of the volvelles have as mater a circular ZODIAC like all the longitude volvelles. Some have a circular CALENDAR like #2 that has January – December along the circumference. Apianus reuses these maters, all the longitude maters are identical and printed from the same printing block only later painted differently. This was evidently a good way of saving a lot of labour.

All the volvelles in AC are made in the same way. On the page itself a background is printed, what I call a MATER. Then, on top of that, on SOME of the volvelles one or more disk layers are stacked and fixed by threads. Many of the volvelles have as mater a circular ZODIAC like all the longitude volvelles. Some have a circular CALENDAR like #2 that has January – December along the circumference. Apianus reuses these maters, all the longitude maters are identical and printed from the same printing block only later painted differently. This was evidently a good way of saving a lot of labour.

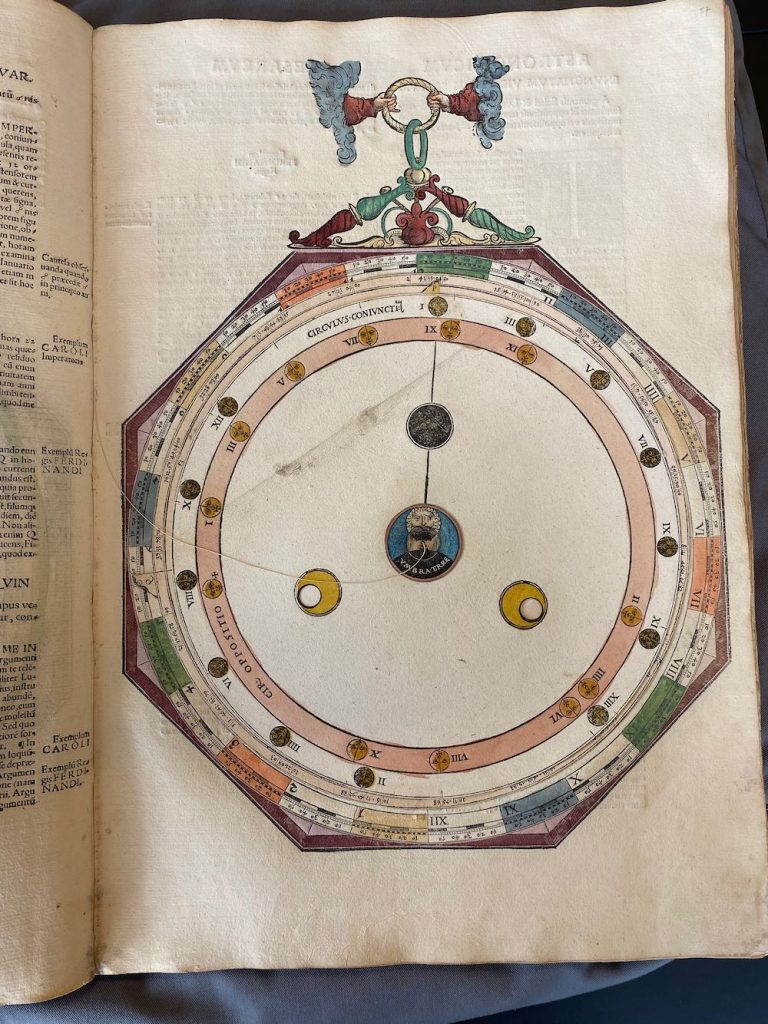

Now, both your #14 and #21B have a mater that on the left semi-circle rim has Arabic HOUR numbers 1-12 and on the right semi-circle rim Roman HOUR numbers I – XII. Let’s call this type of mater an “HOUR mater”. #21B, your sunrise/sunset volvelle, only has a single HOUR mater with no layers. Now assume we do the following (hypothetically):

1) Move the two layers of #14 on top of #21B. Then this voilvell would be correct sitting on the corect mater and in the right place.This is the volvelle for conjunction and opposition hours.

2) Move all the layers on top of #2 to the now free mater #14. Except for the mater, this volvelle will now be in the correct place. This is the volvelle for the Moon’s longitude.

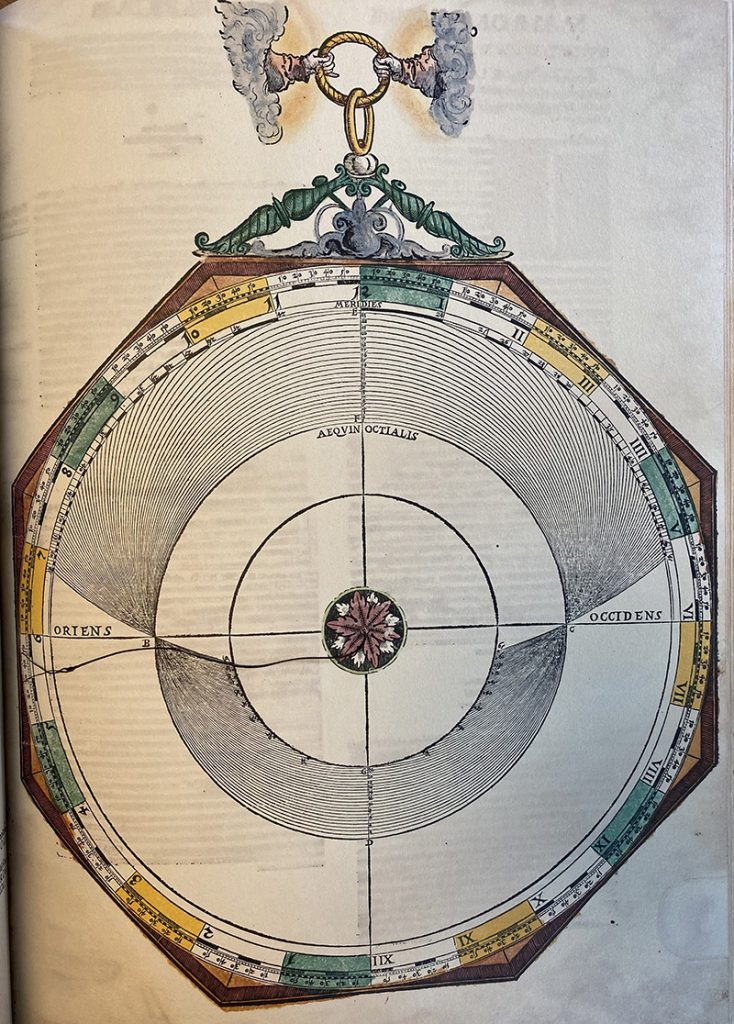

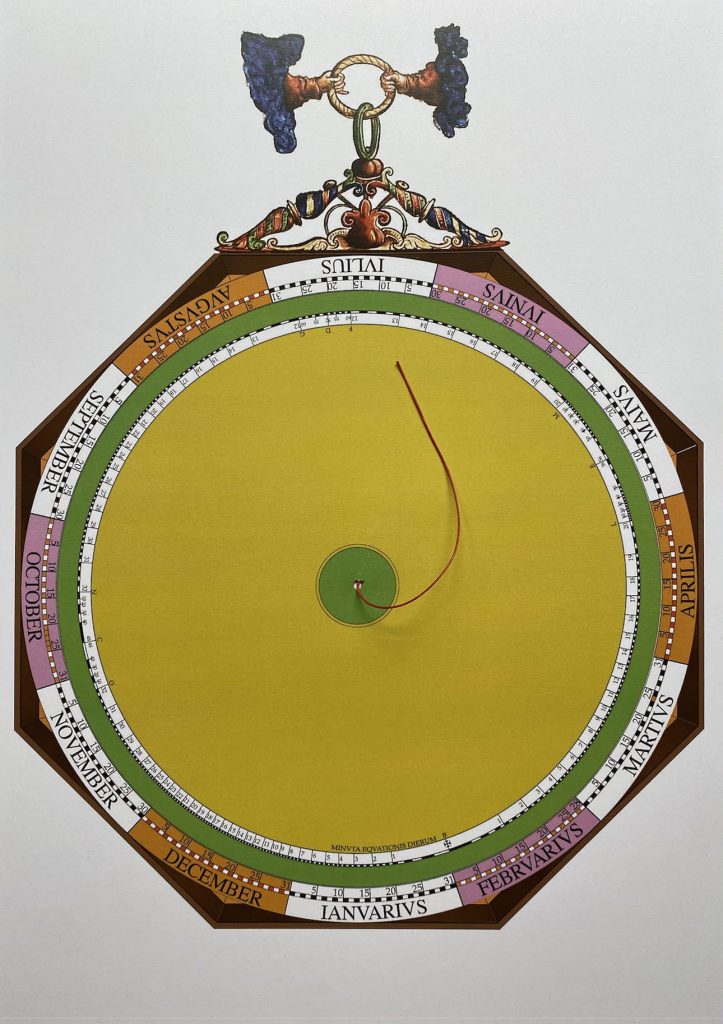

3) #2 will now only be the CALENDAR mater and will be correct and in the right place. This is the volvelle for the equation of time, EQUATIONIS DIERUM.

4) The central part of the mater #21B will be hidden and in this ways has disappeared. Sunrise/sunset has disappeared and is no more problematic.

The correct sequence of volvelles is now reestablished and all are correct with the exception that #14, the Moon’s longitude, has the wrong mater which I think could be a misprint in the fabrication of the facsimiles.

Hier het artikel van Owen Gingerich uit 1971 over de facsimile uitgave en de fouten die bij het produceren zijn gemaakt:

Beschrijving van de volvelles

De originelen zijn allemaal verschillend. Deze basis is 750 keer hetzelfde; alhoewel… De eerste 200 zijn handgekleurd, de rest gedrukt. Eerst maar eens de ene van de andere volvelle zien te onderscheiden door ze allemaal op volgorde te plaatsen, met een uitleg per volvelle. Wikimedia Commons hielp met namen en volgorde. De paper van Lars Gislen van de Universiteit van Lund leverde alle inzichten en werking. Ik kopieer zijn teksten zodat het bij de volbelles staat, maar zijn volledige paper kun je hier vinden. Ik start met de pagina in mijn boek (ongenummerd), maar voor een goede uitleg beter om de pagina nummering van Lars aan te houden. > Teksten van Lars ONDER de foto’s in grijze kaders.

Bij nummer 2, 14 en 21 zie je dubbele pagina’s: dit zijn de fouten in de facsimile die ik (met veel hulp van Lars) zo goed mogelijk heb gepoogd uit te leggen. De correcties staan in rode vlakken.

INDEX: 36 totaal waarvan 21 met lagen, 15 zonder:

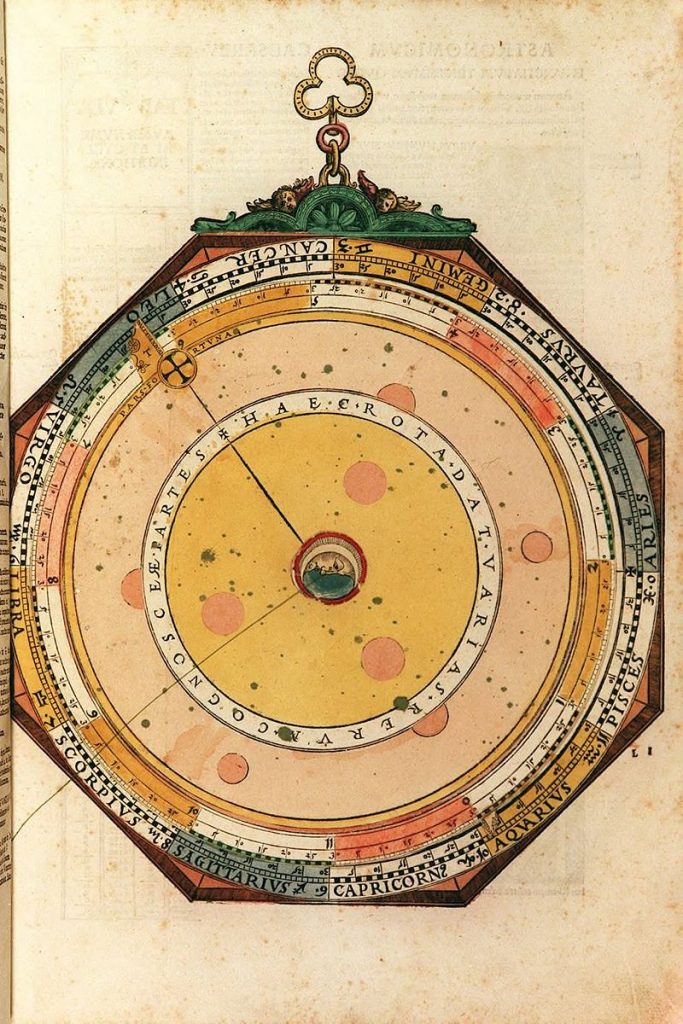

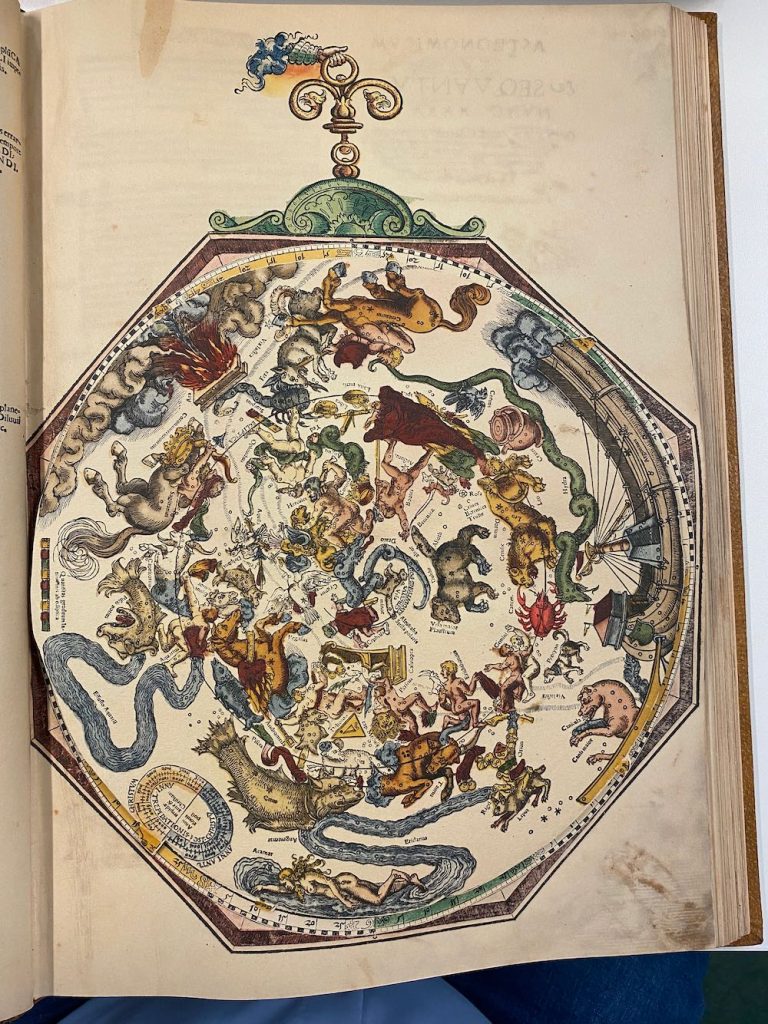

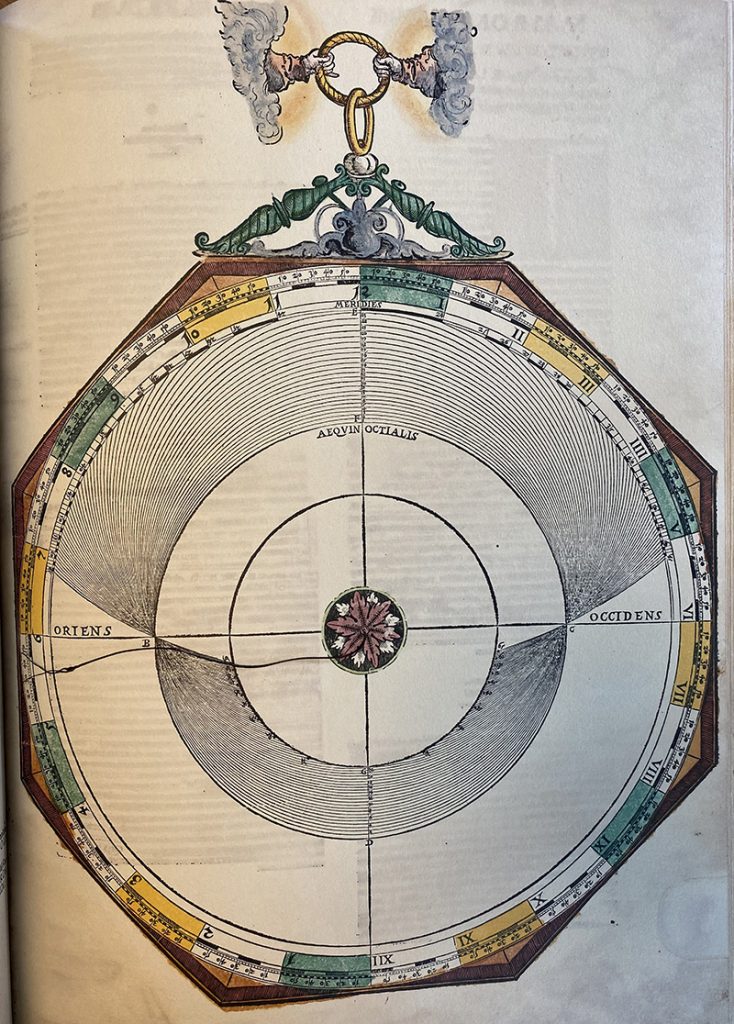

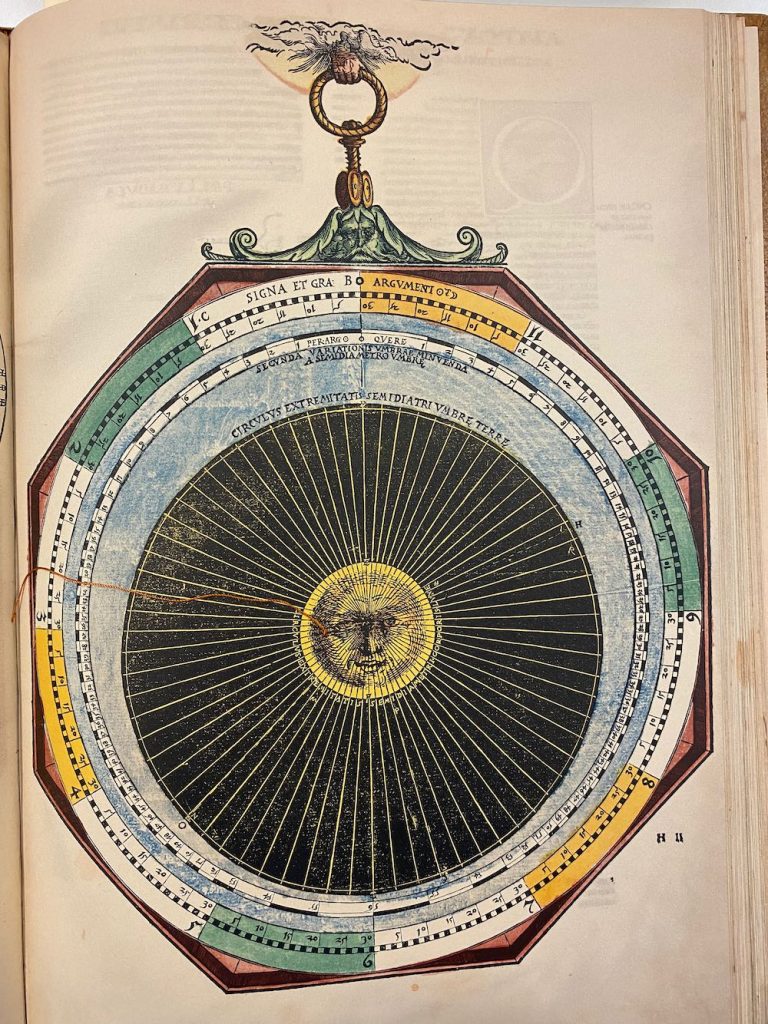

Nummer 01 – P13: The Sky Volvelle [1 laag]

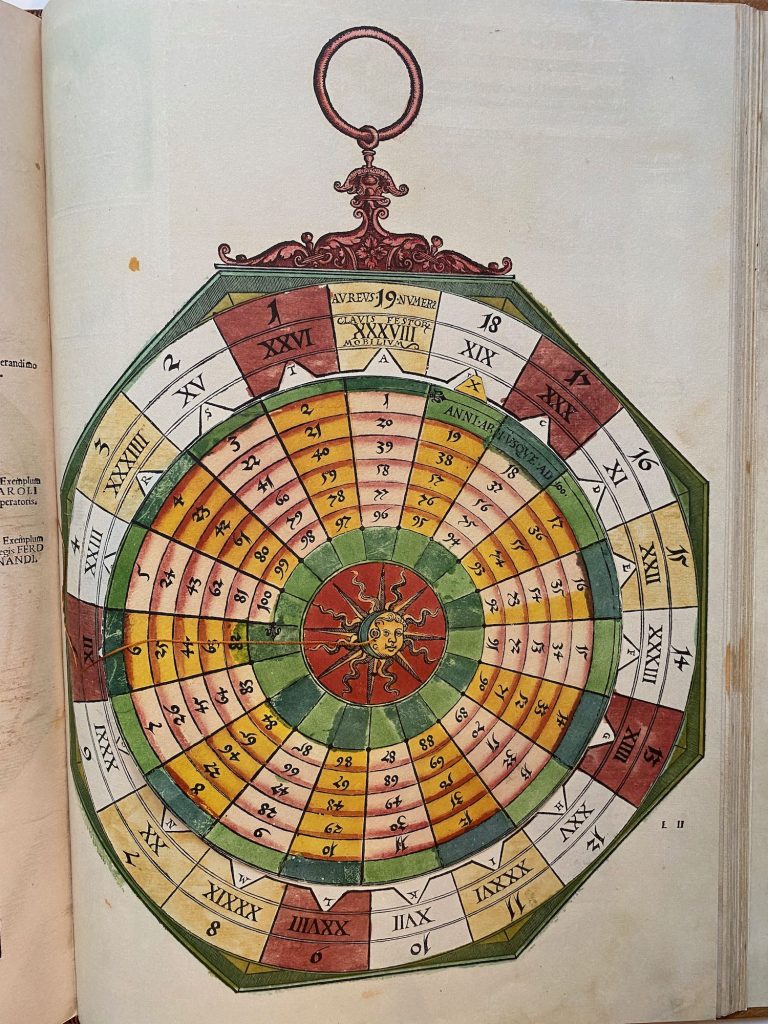

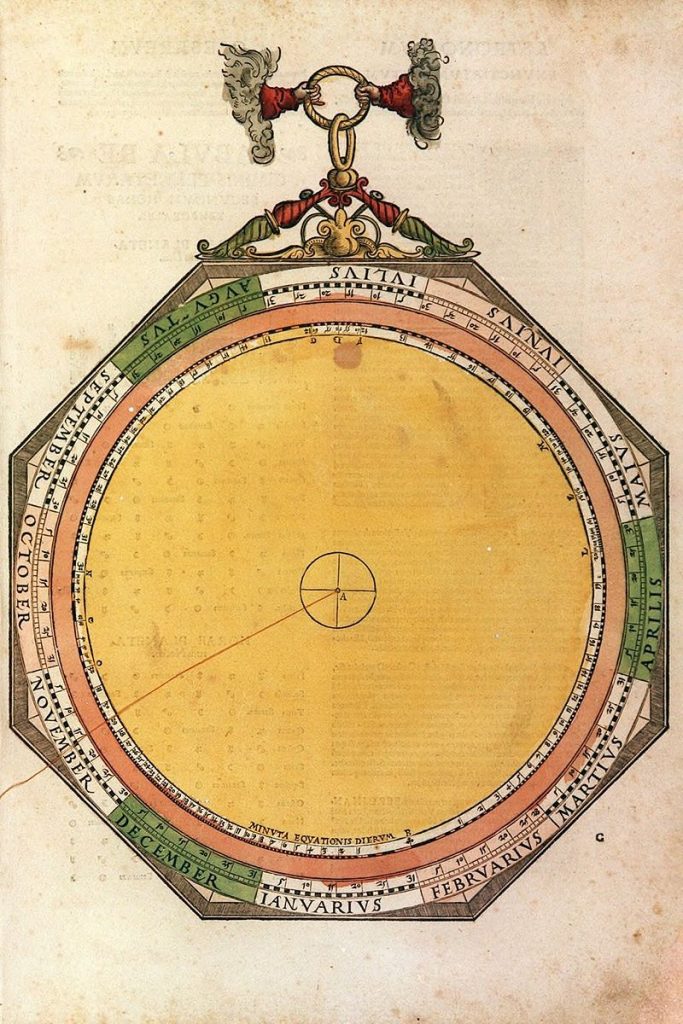

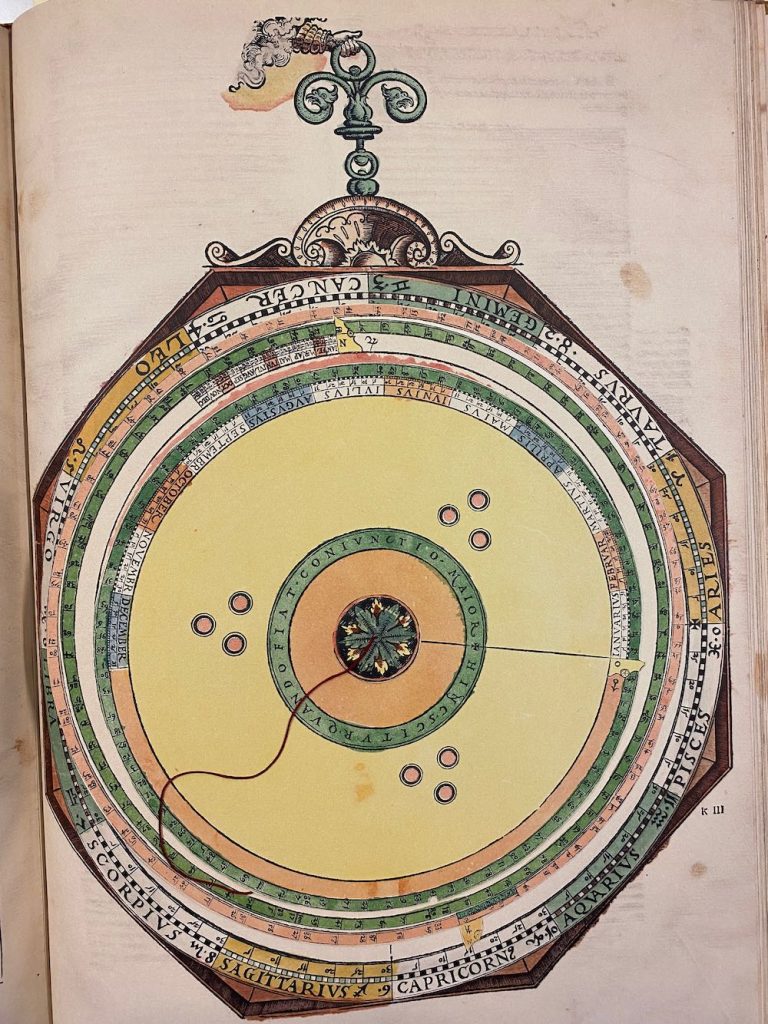

Nummer 02A – P17: The Equation of time [geen lagen] >>> 2B [7 lagen]

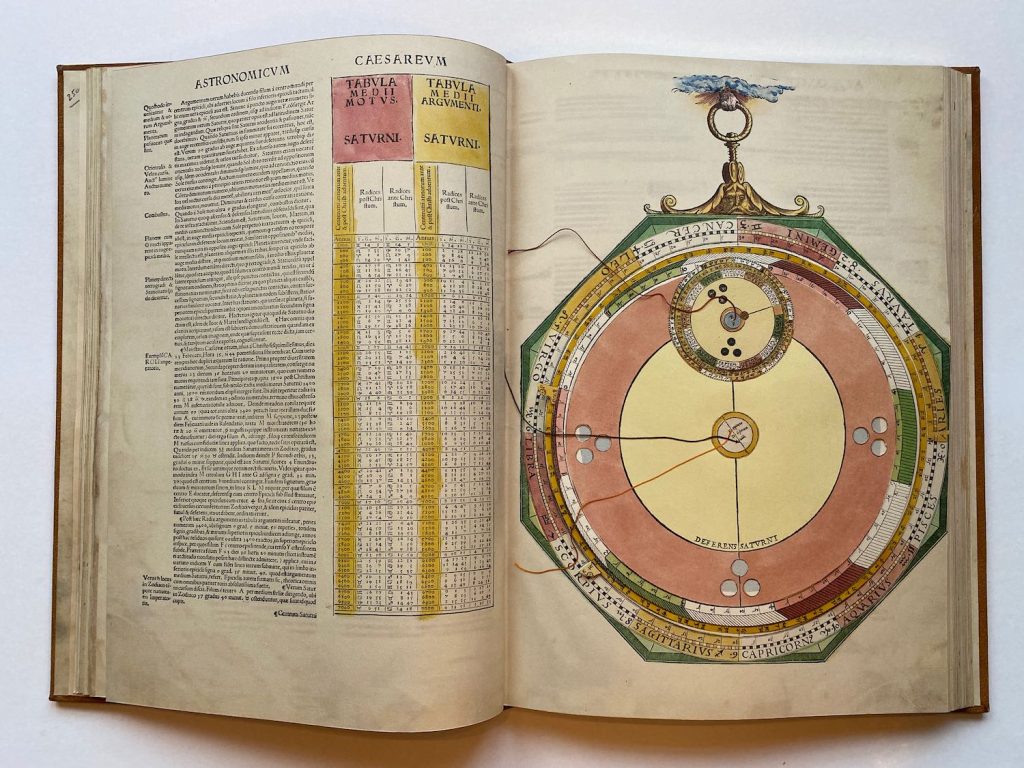

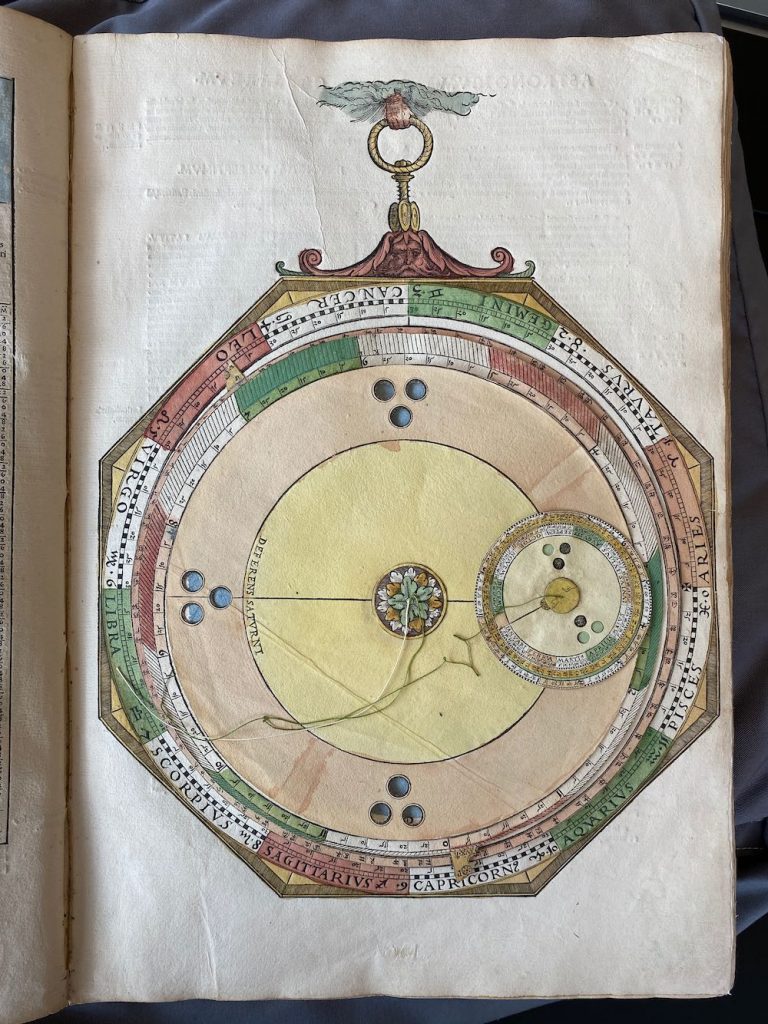

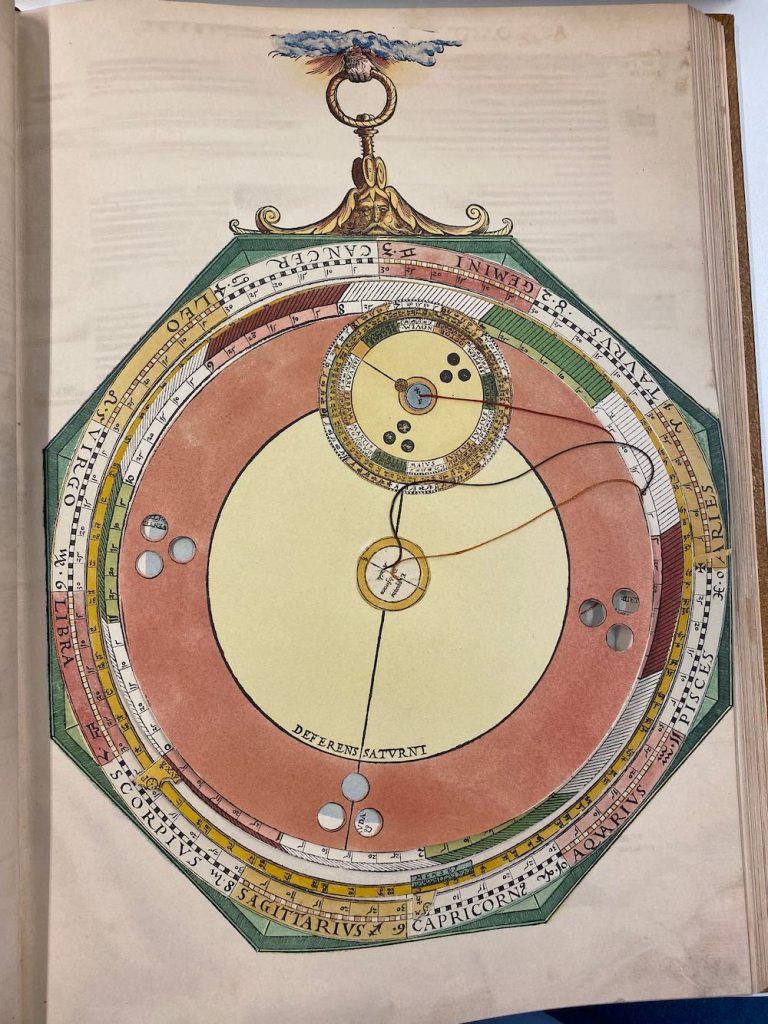

Nummer 03 – P21: The Saturn Volvelle [5 lagen]

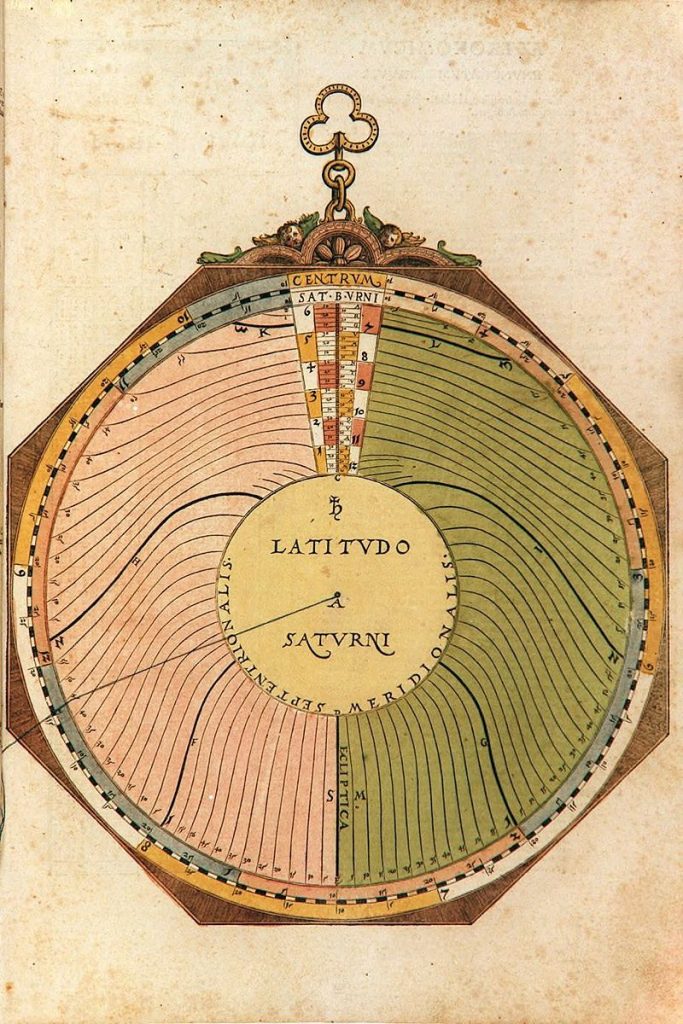

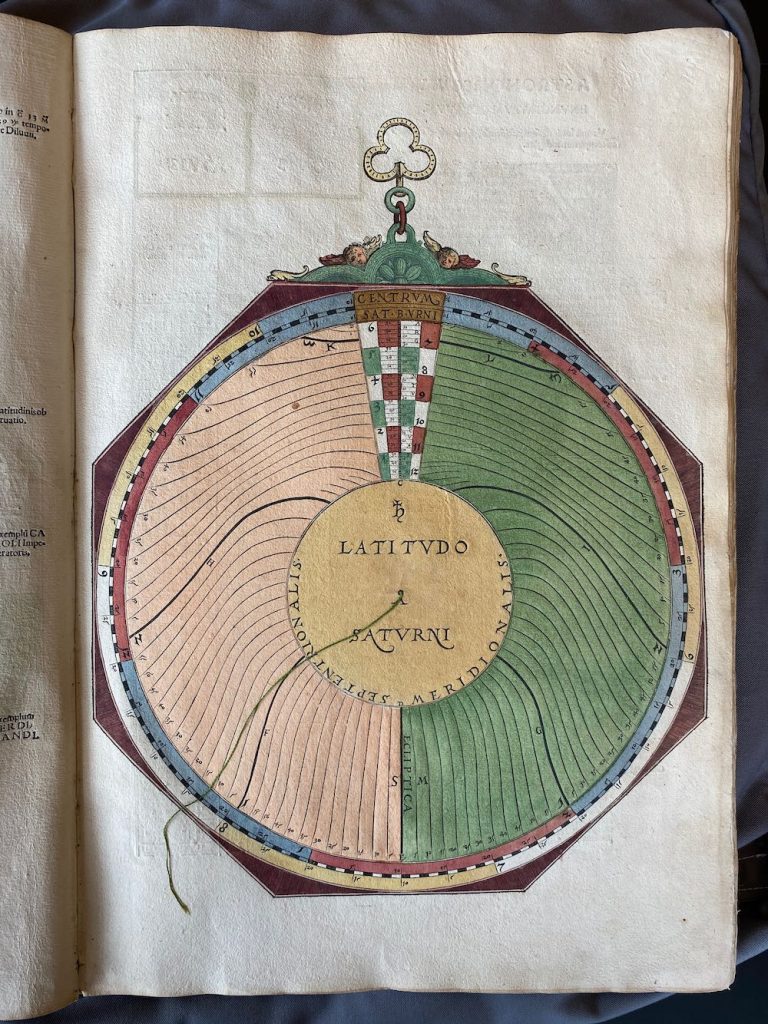

Nummer 04 – P23: The longitude of Saturn [geen lagen]

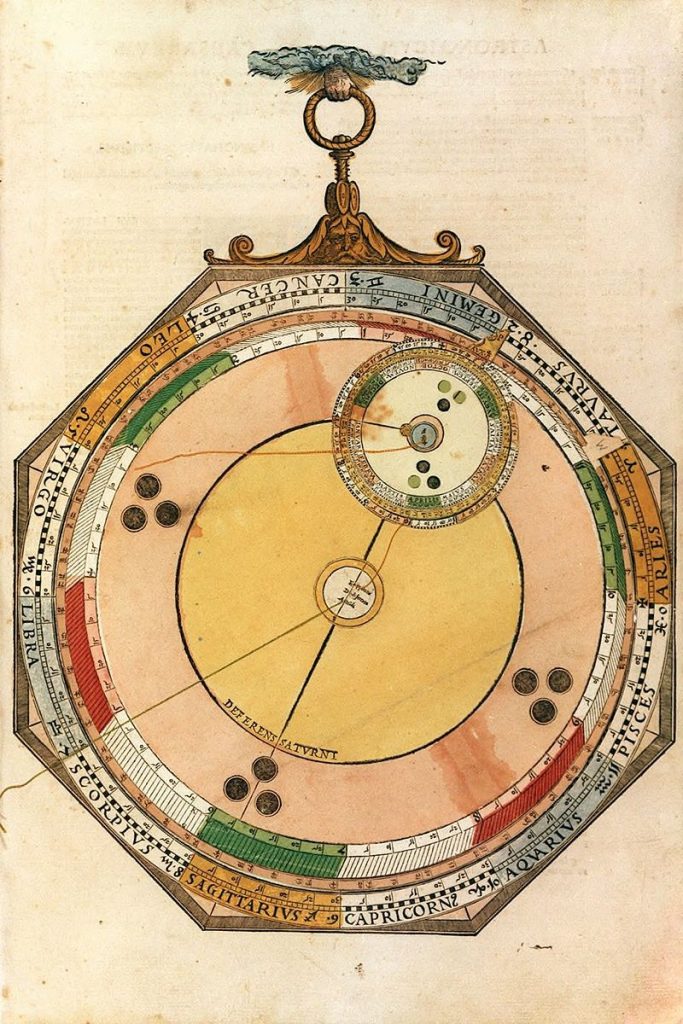

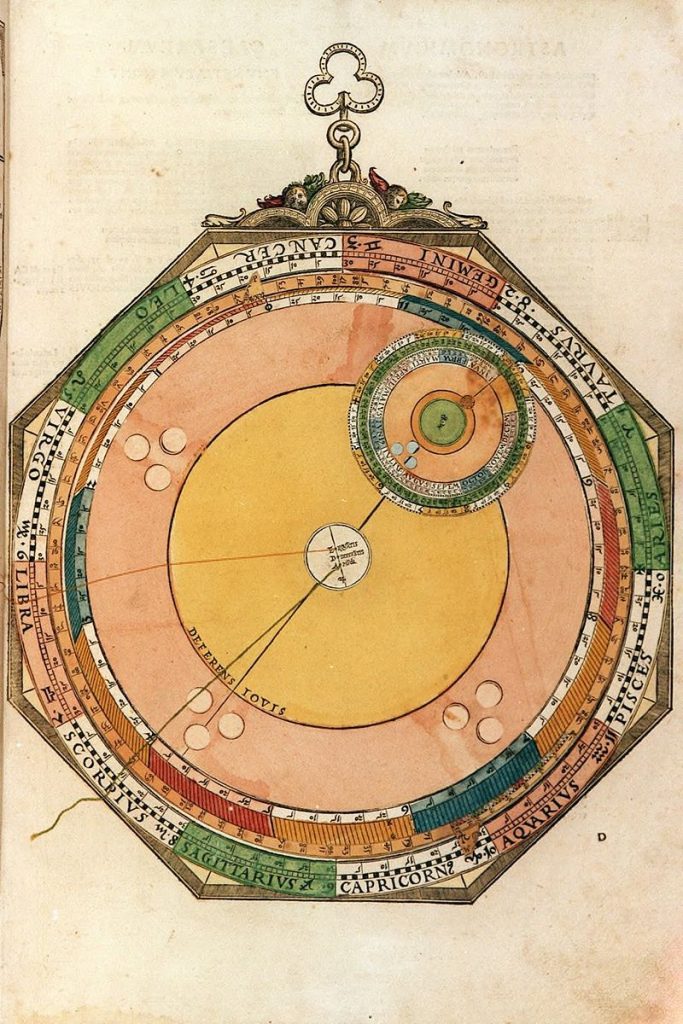

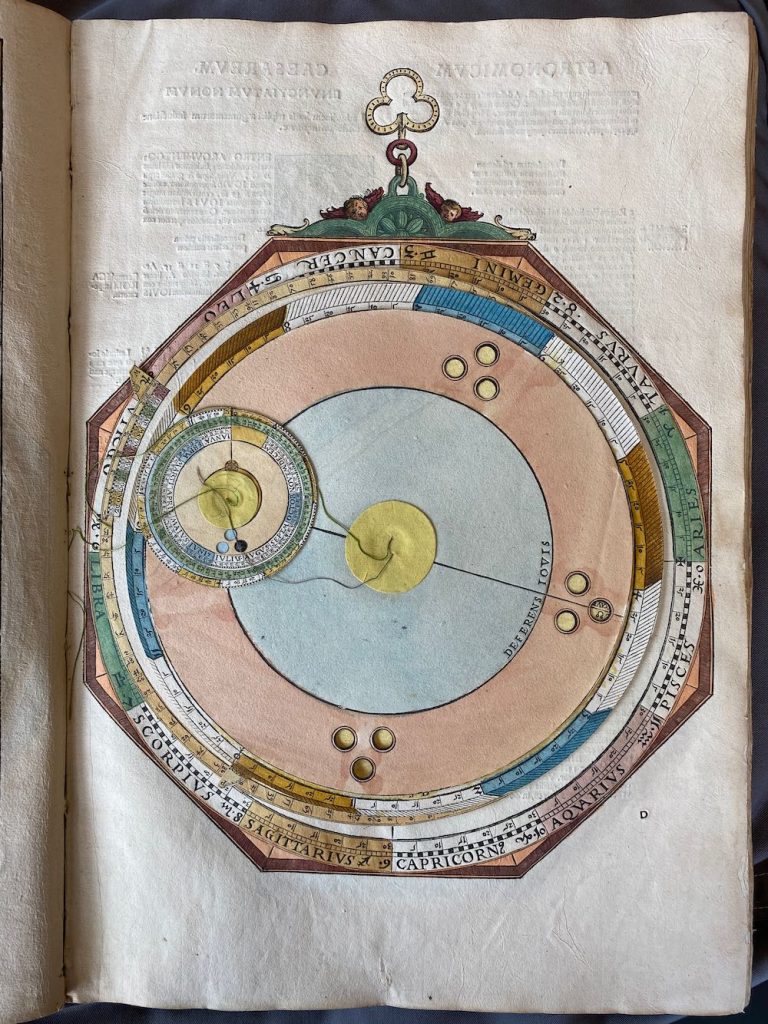

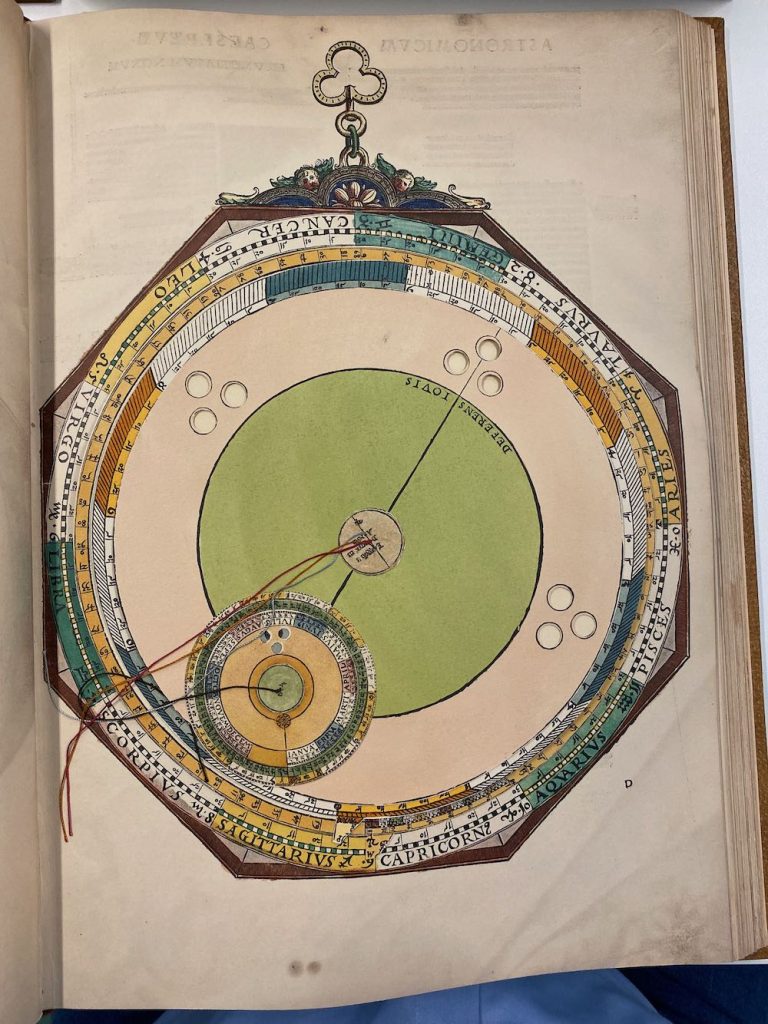

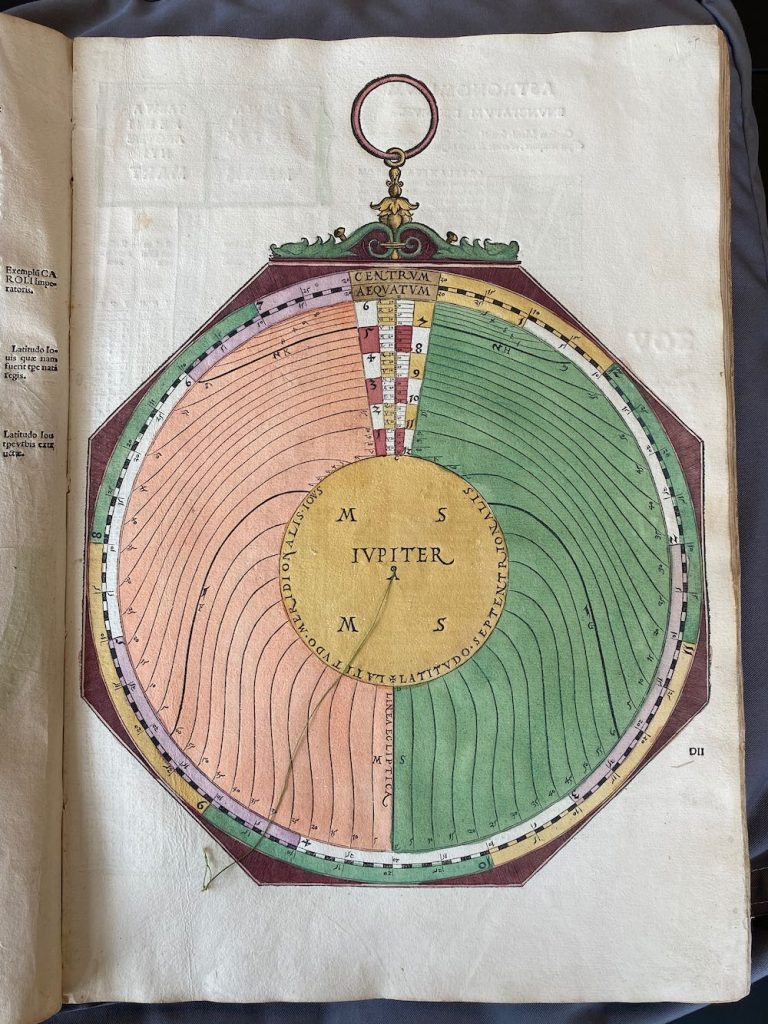

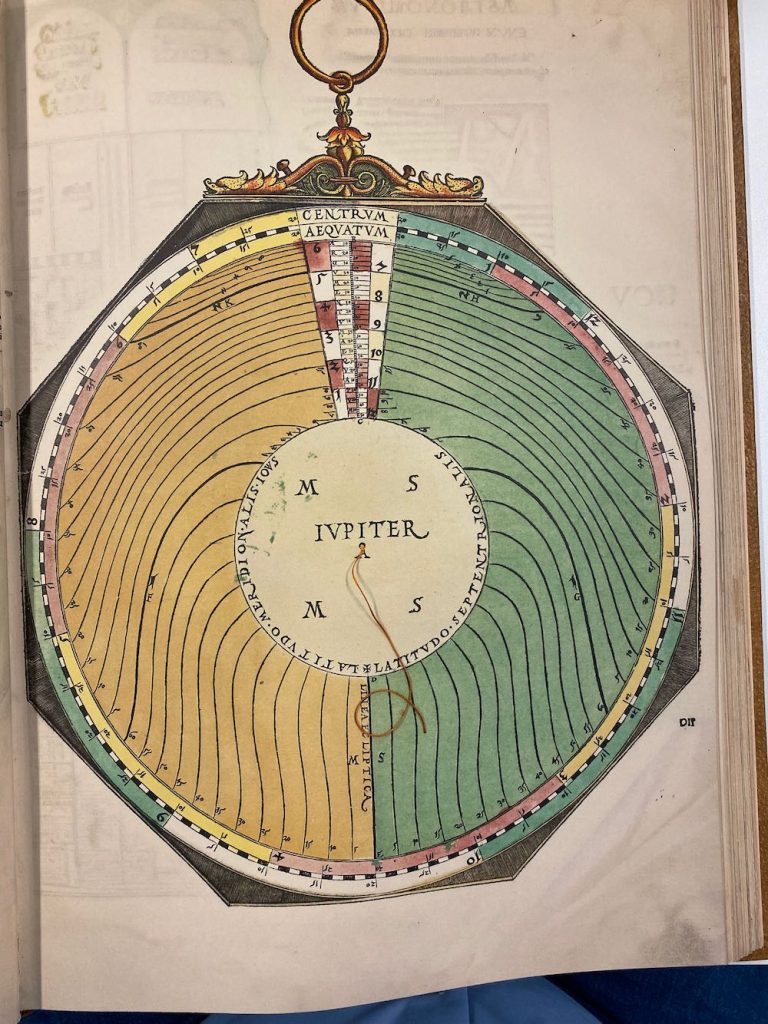

Nummer 05 – P25: The longitude of Jupiter [5 lagen]

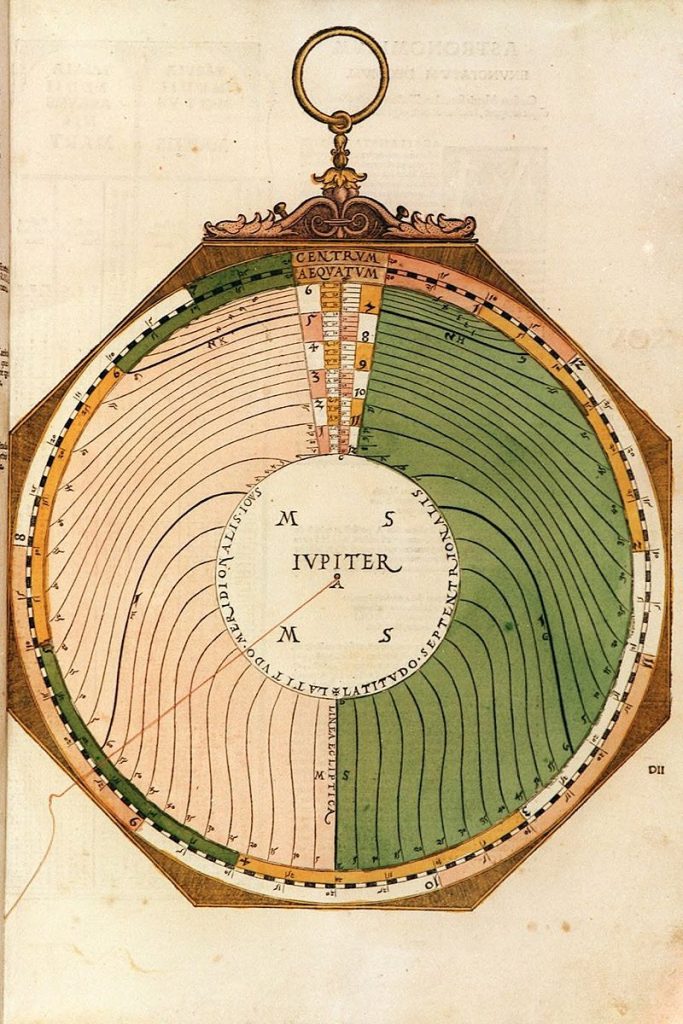

Nummer 06 – P27: The longitude of Jupiter [geen lagen]

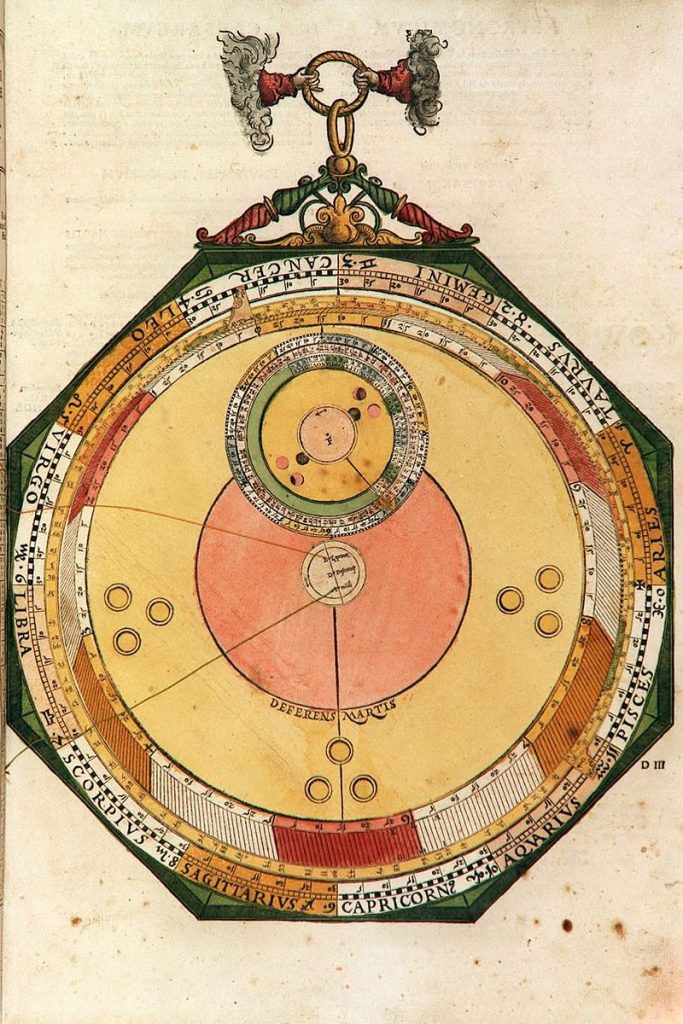

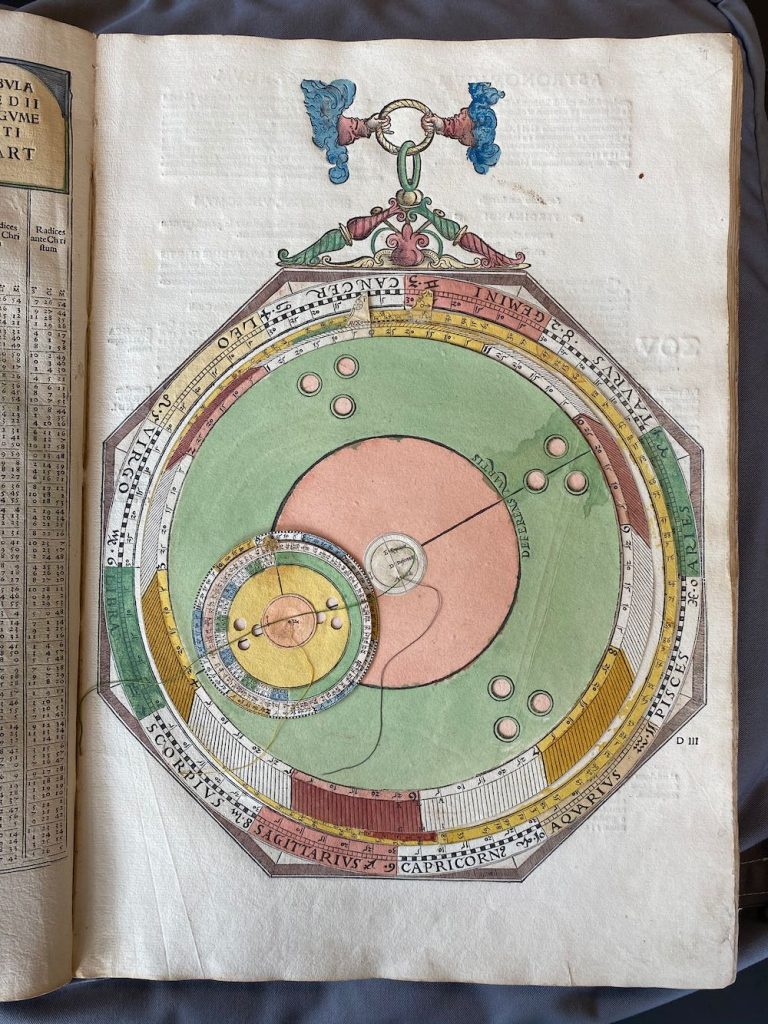

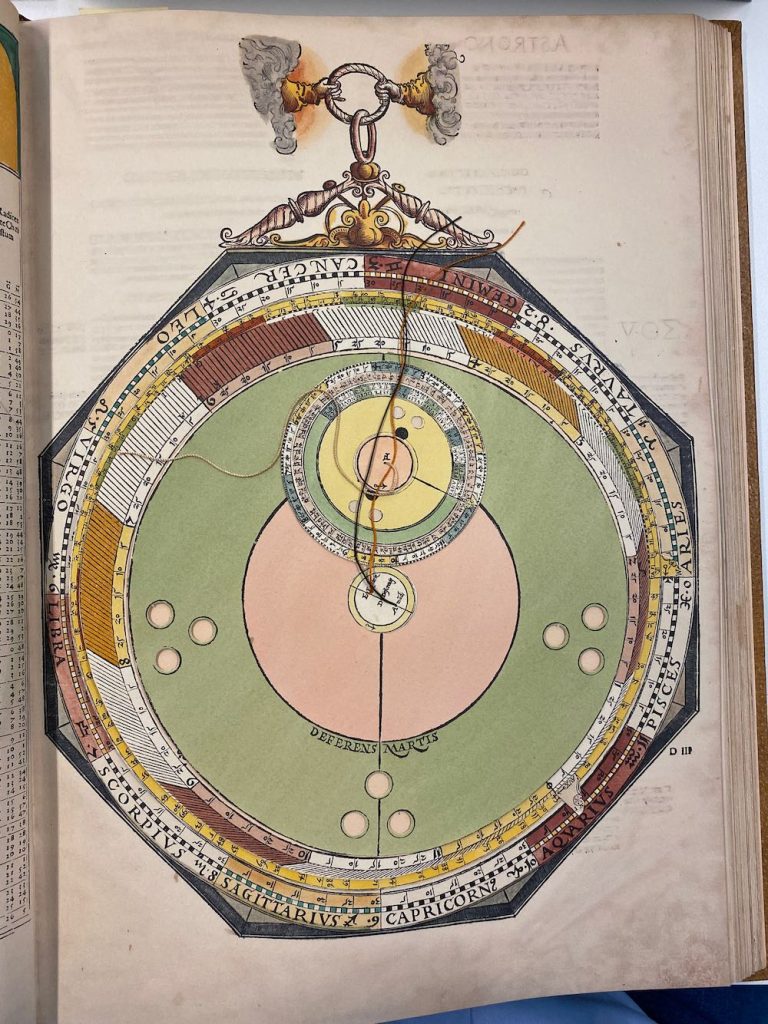

Nummer 07 – P29: The Mars Volvelle [5 lagen]

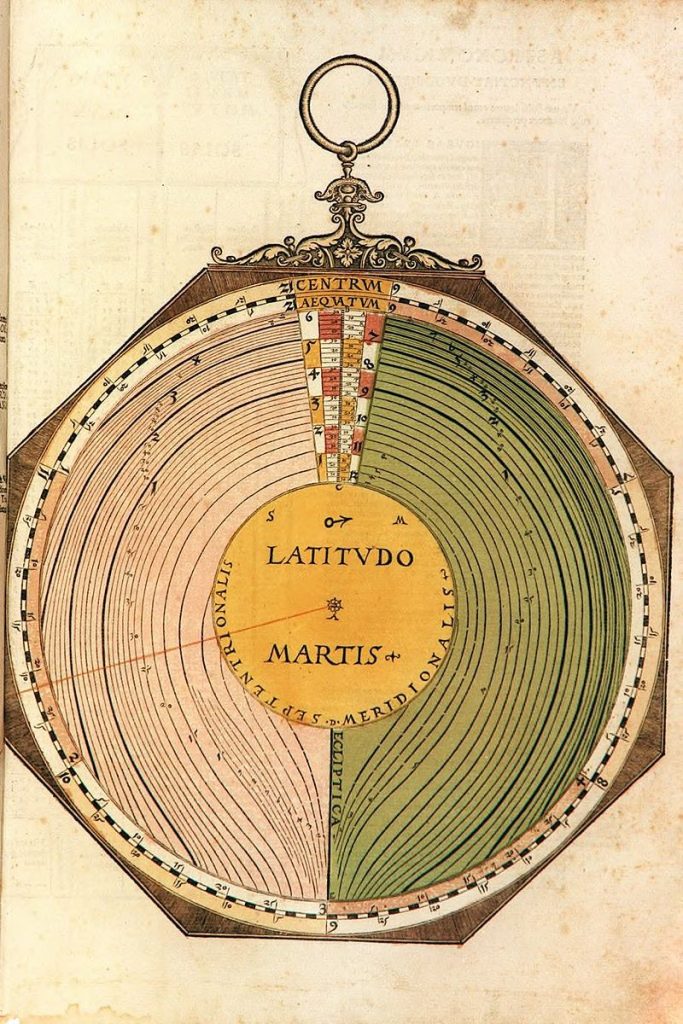

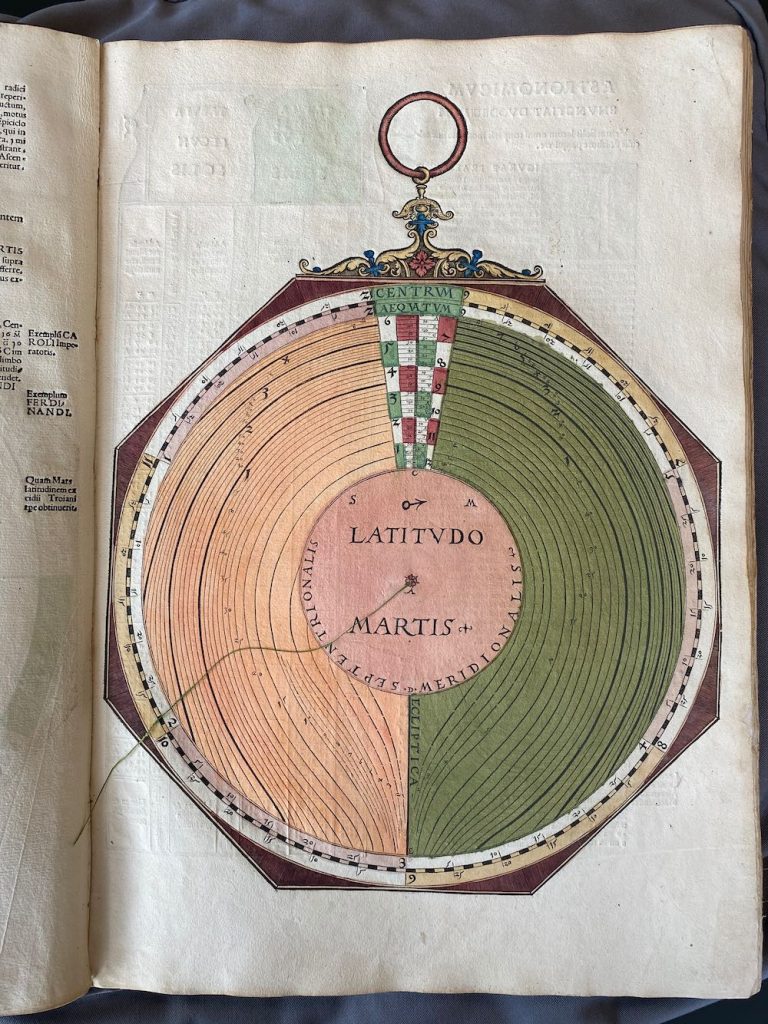

Nummer 08 – P31: The Latitude of Mars [geen lagen]

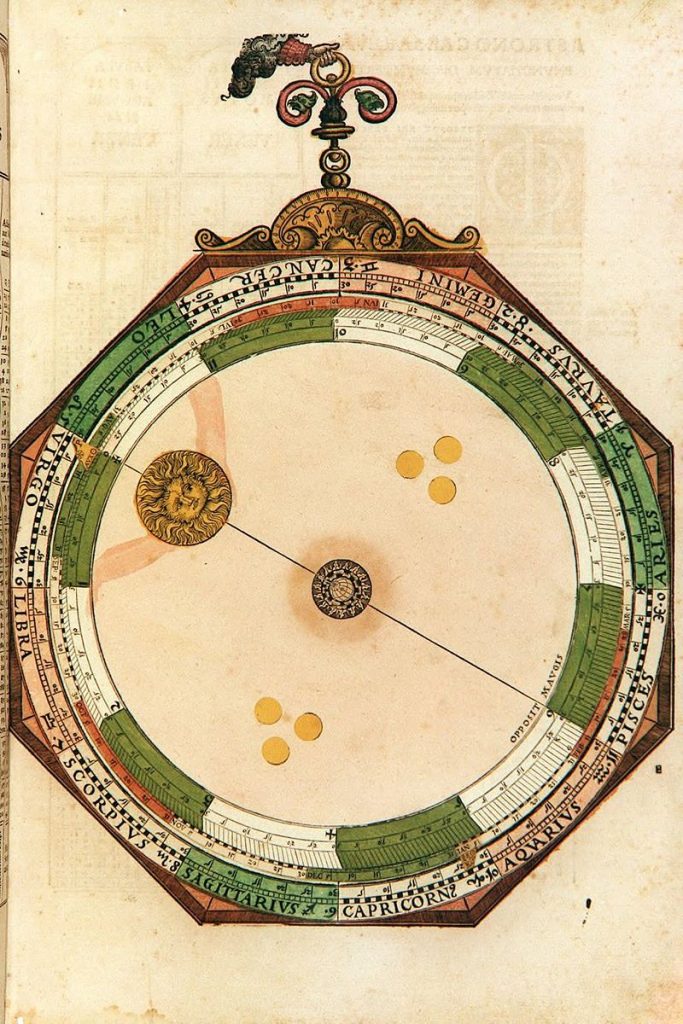

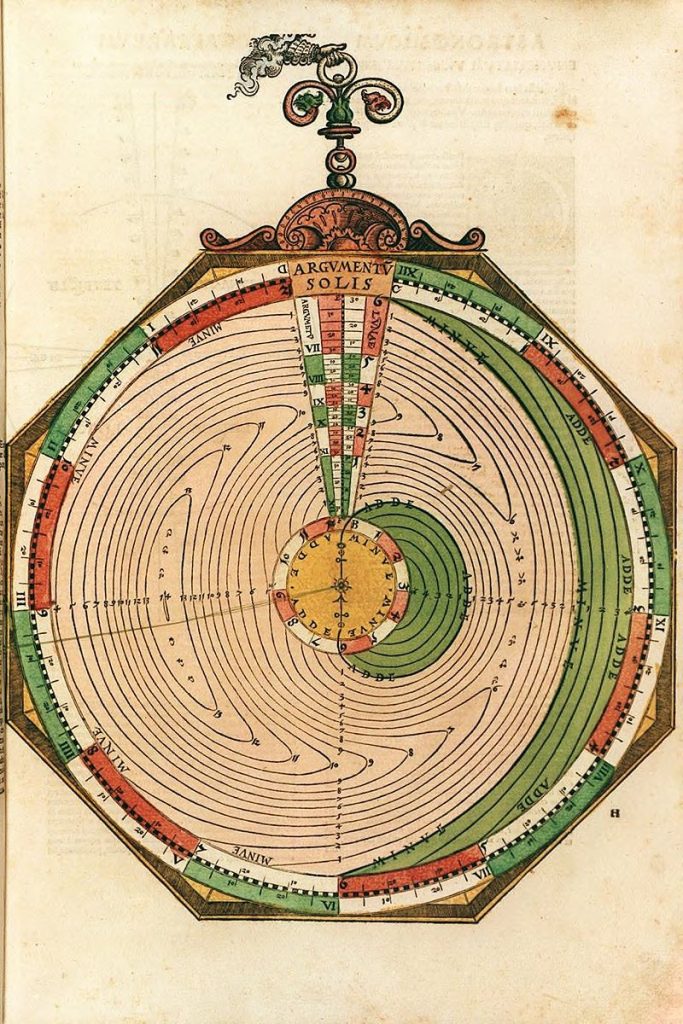

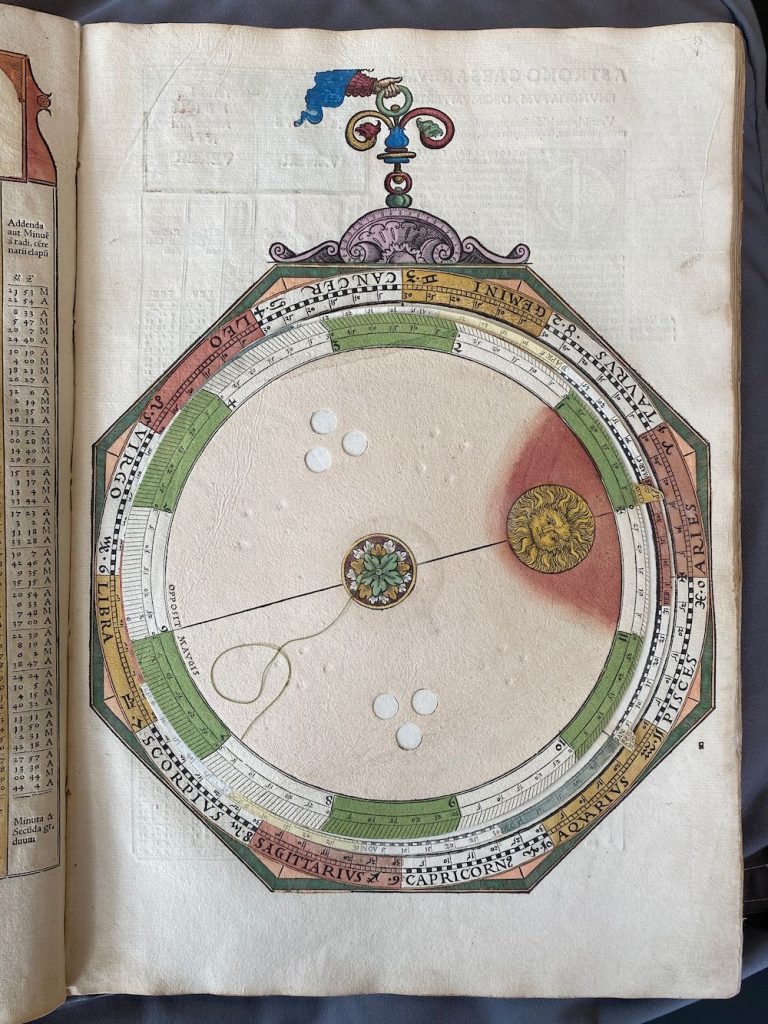

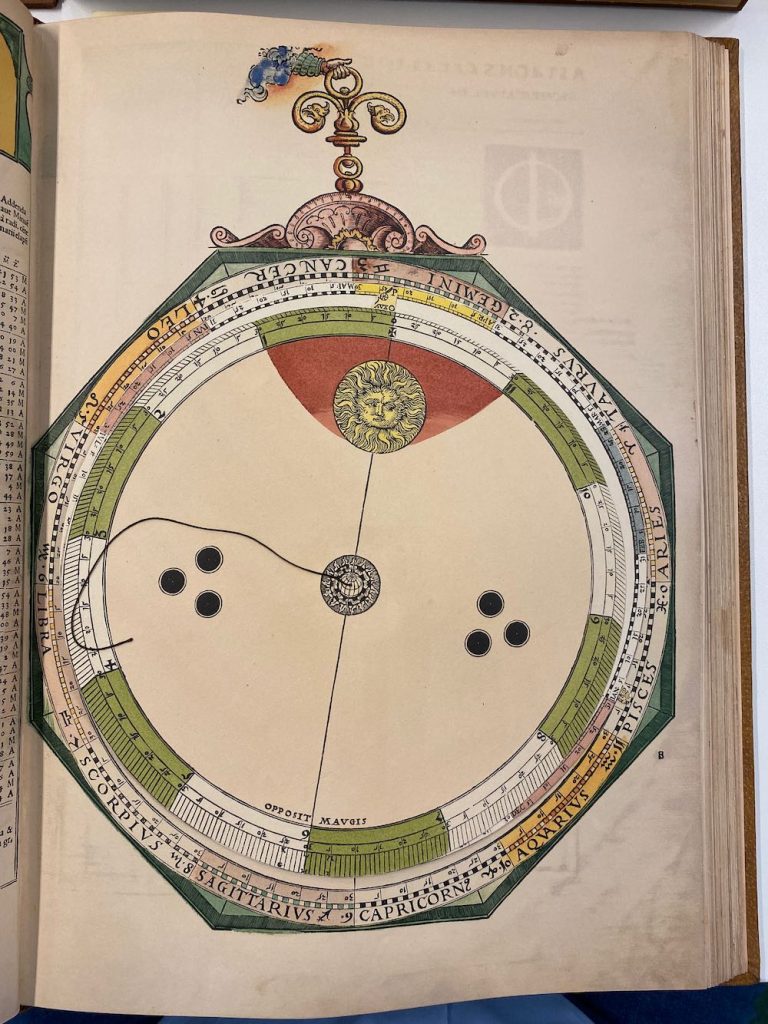

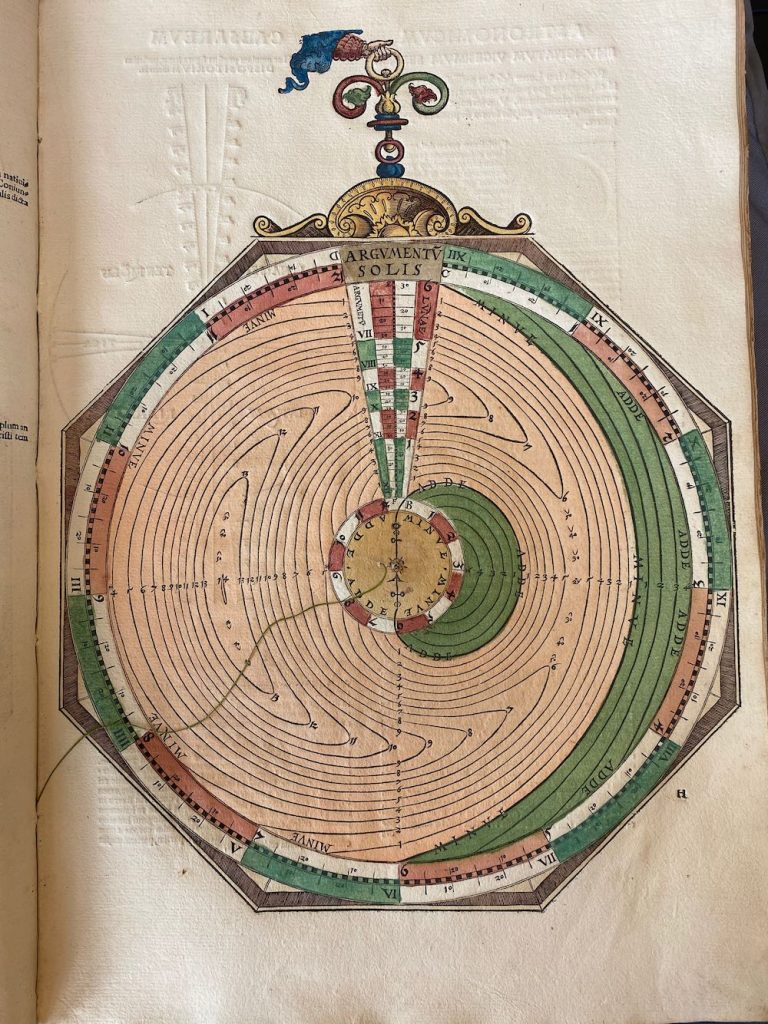

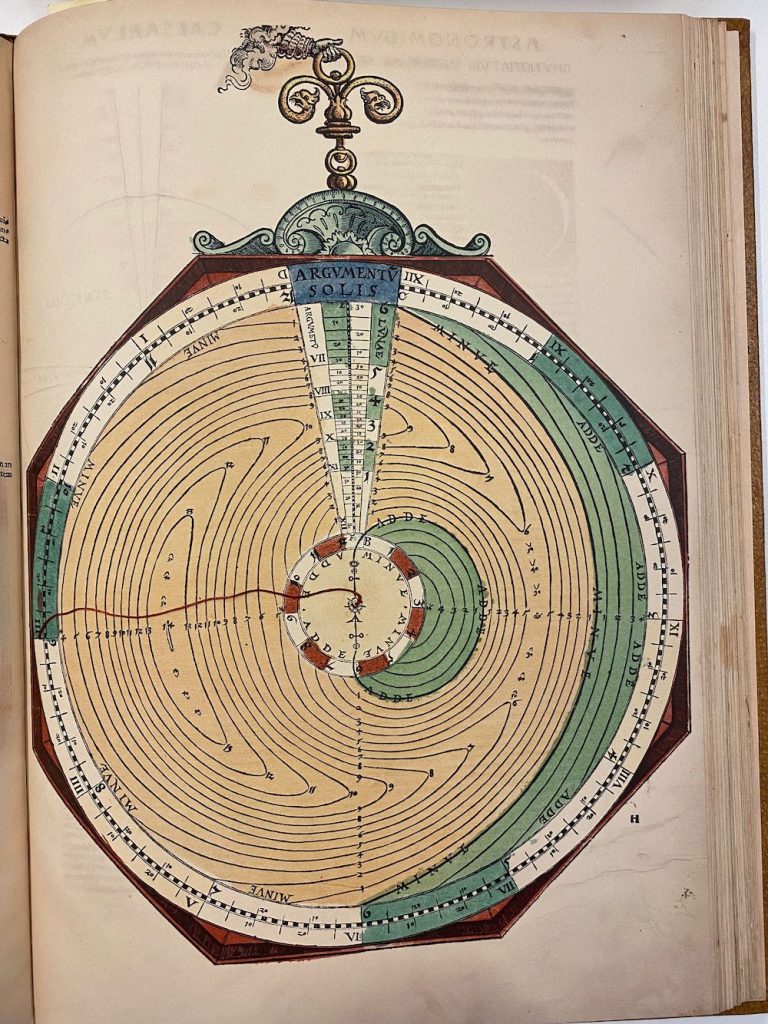

Nummer 09 – P33: The Solar Volvelle [2 lagen]

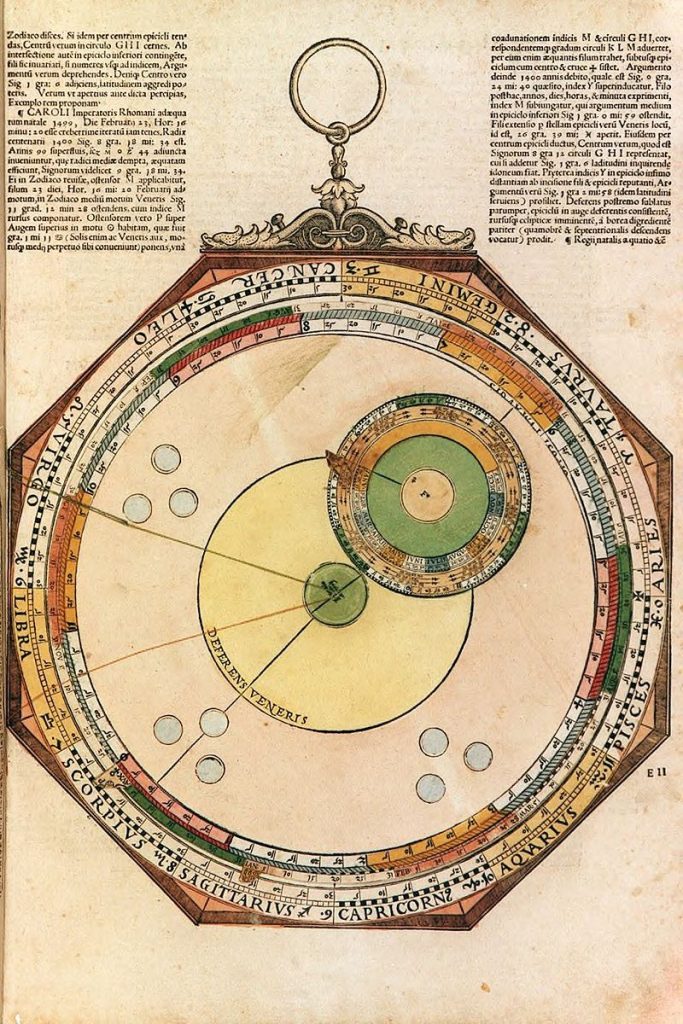

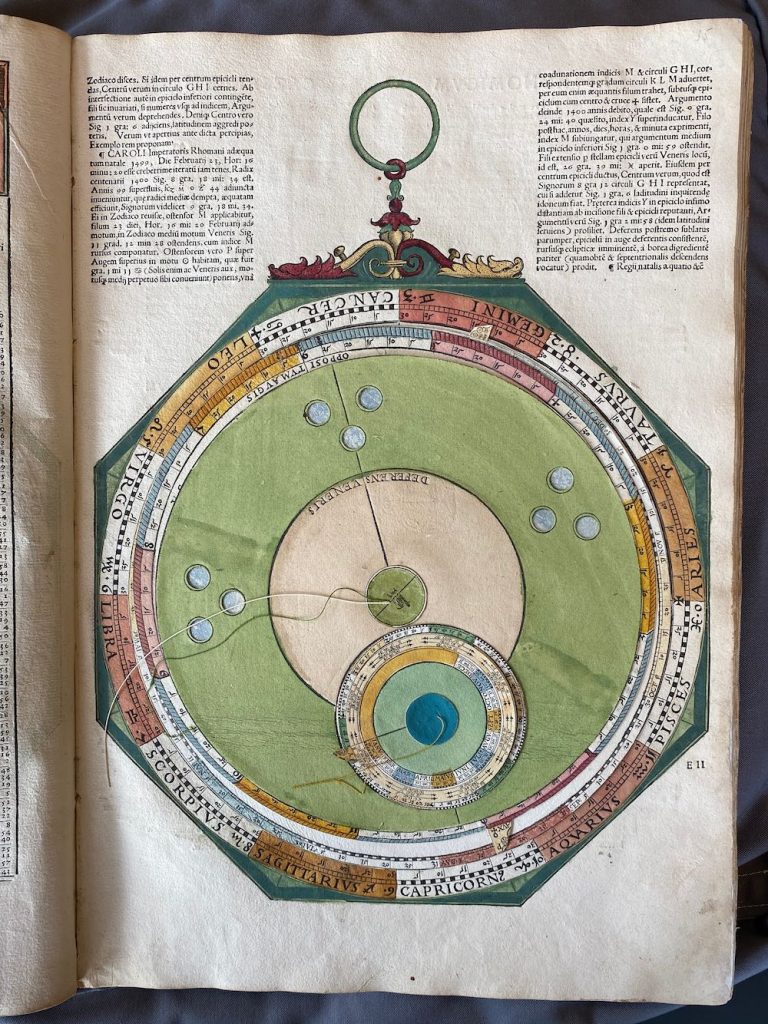

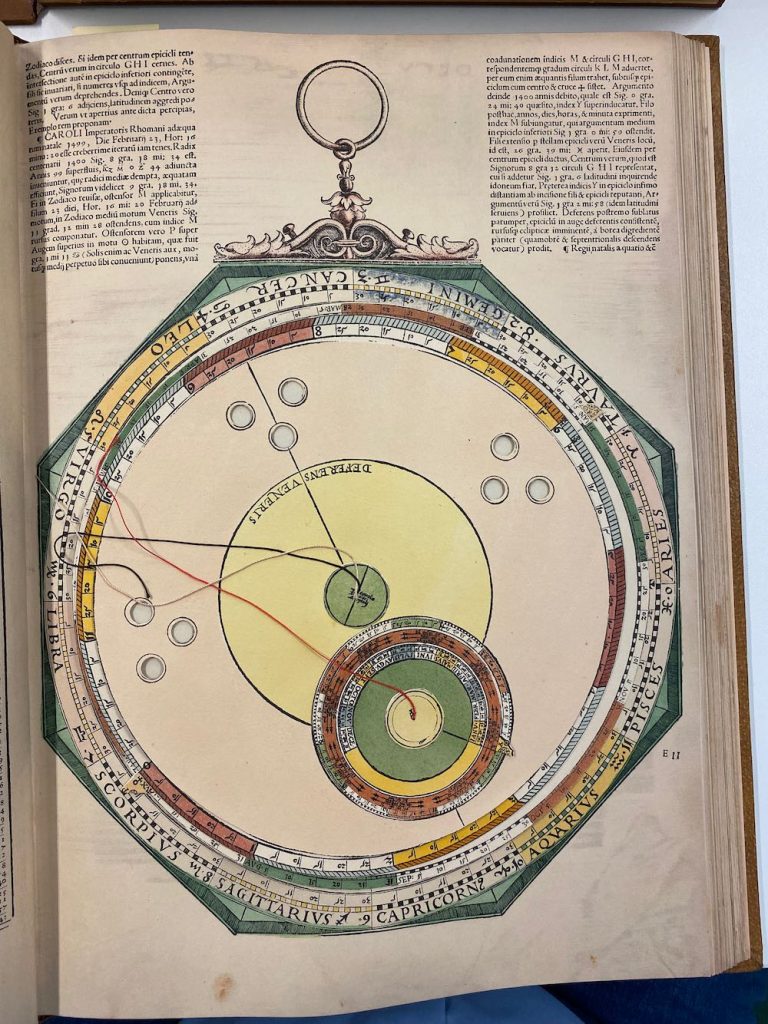

Nummer 10 – P35: The Venus Volvelle [5 lagen]

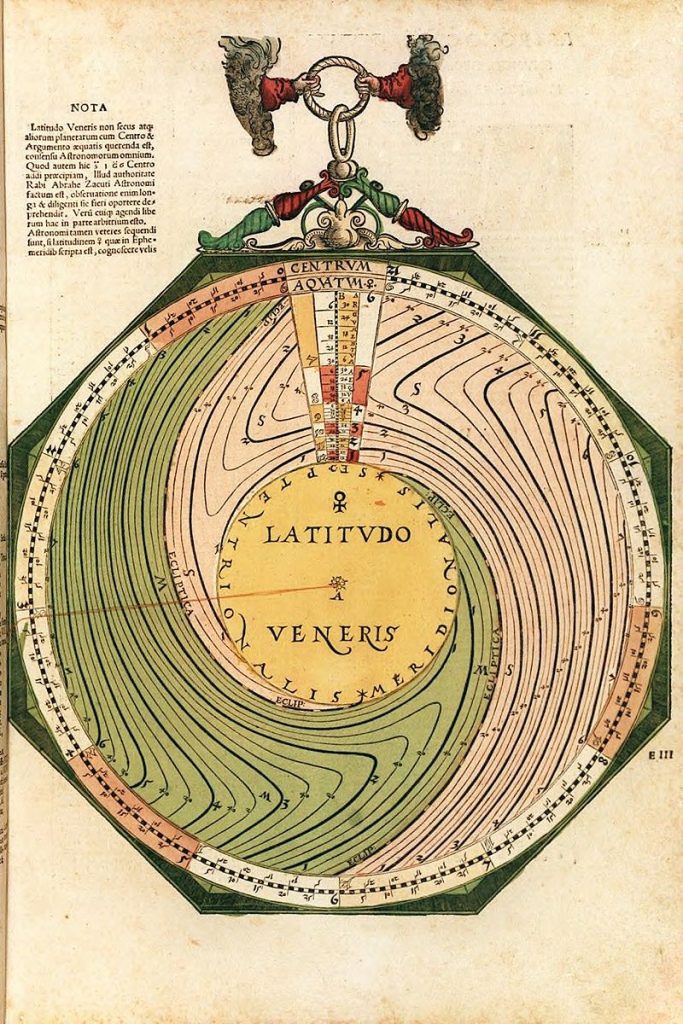

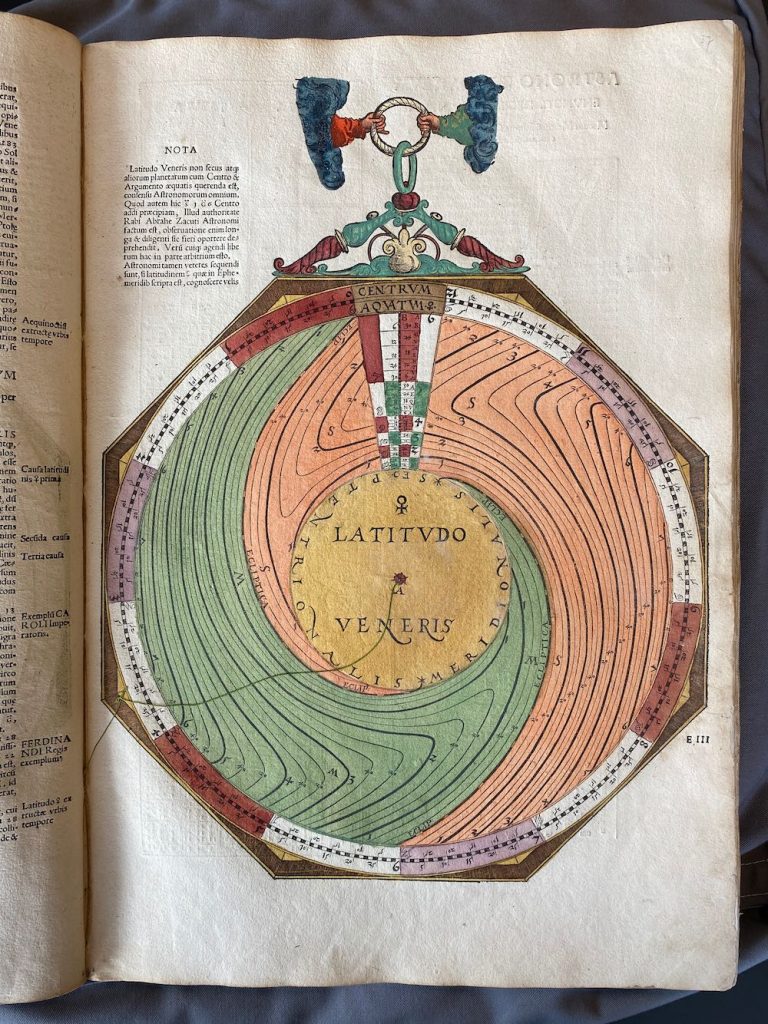

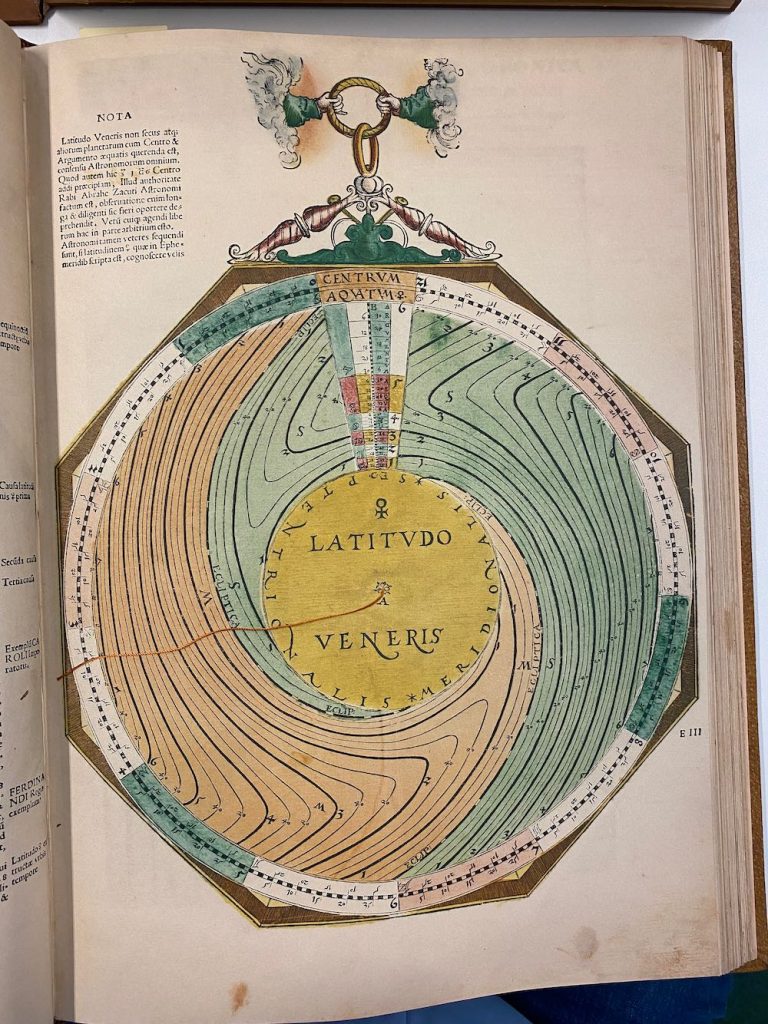

Nummer 11 – P37: The latitude of Venus [geen lagen]

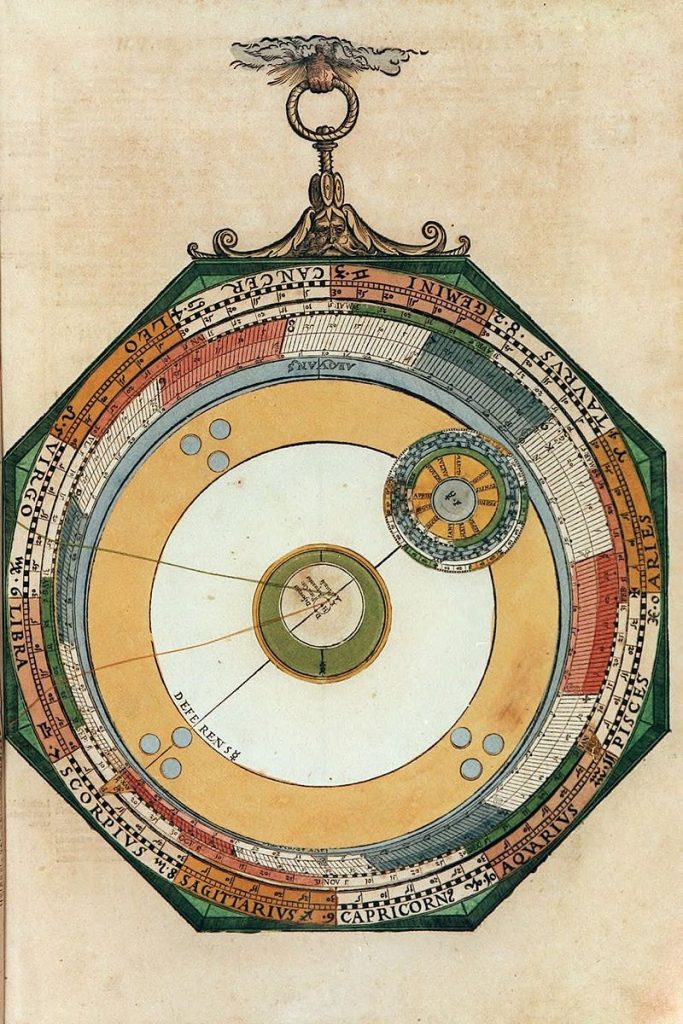

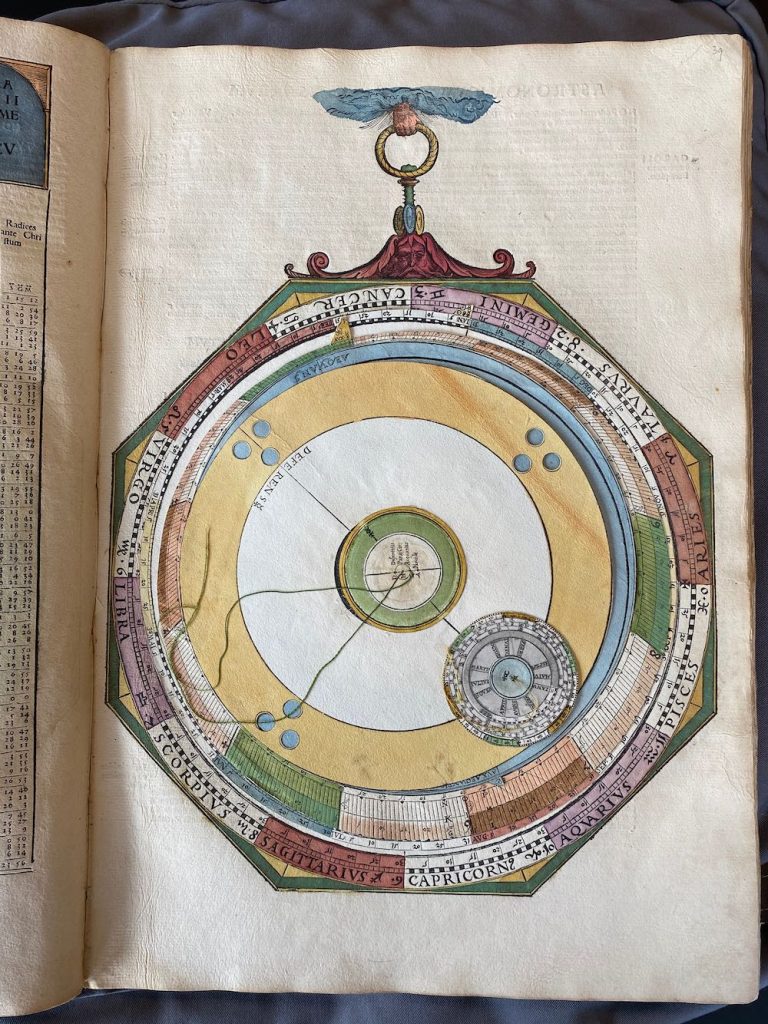

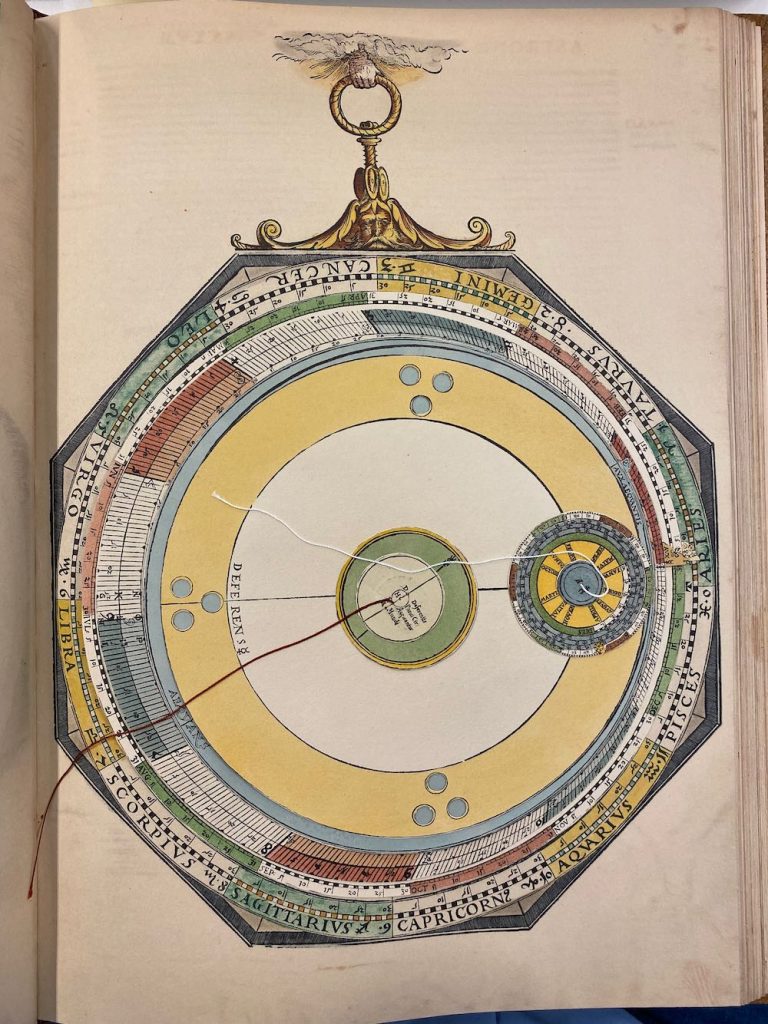

Nummer 12 – P39: The Mercury Volvelle [6 lagen]

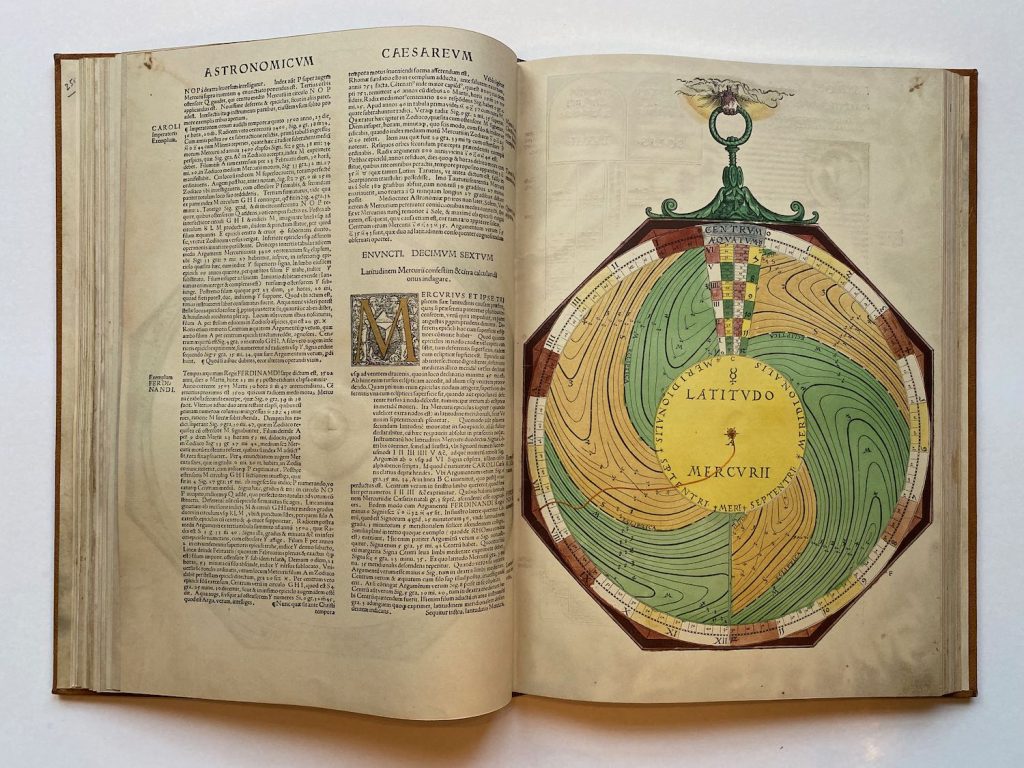

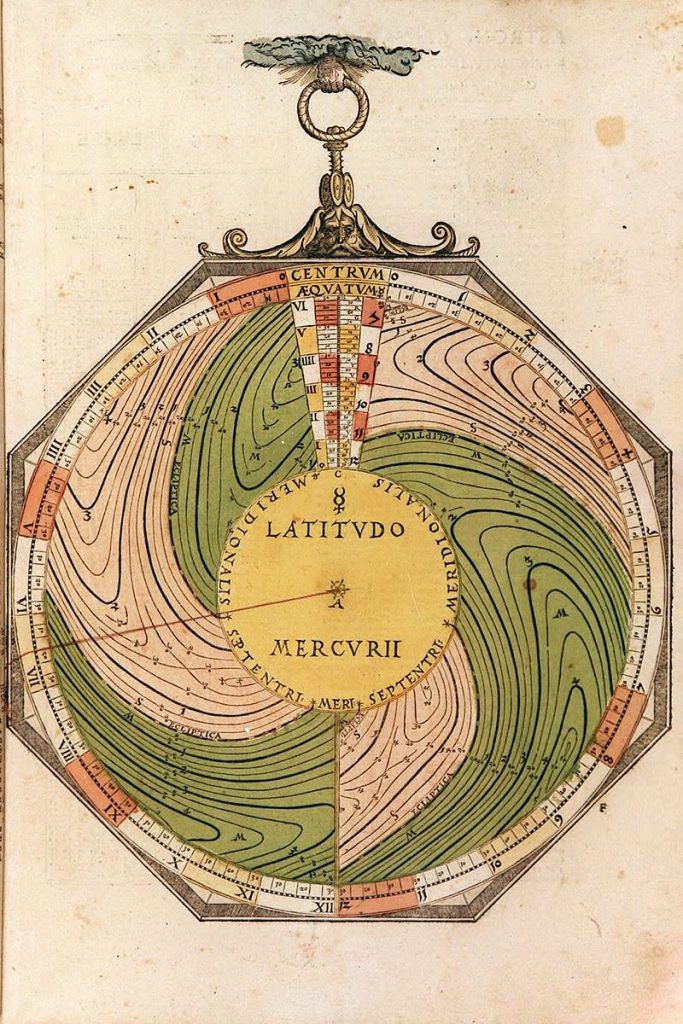

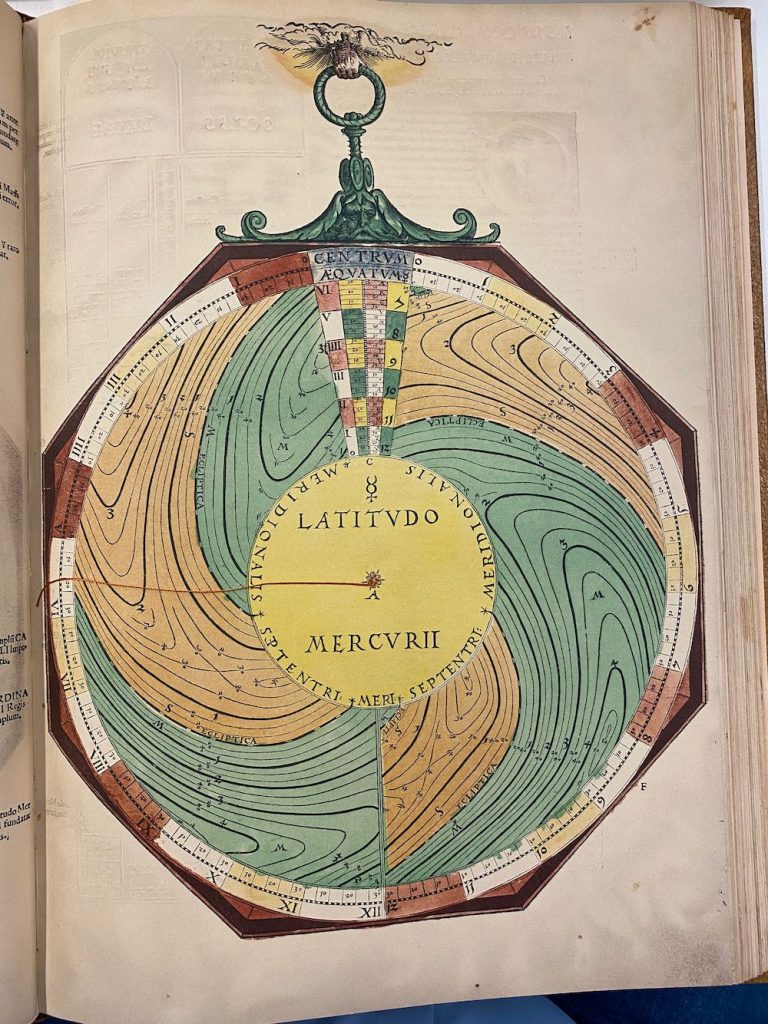

Nummer 13 – P41: The Latitude of Mercury [geen lagen]

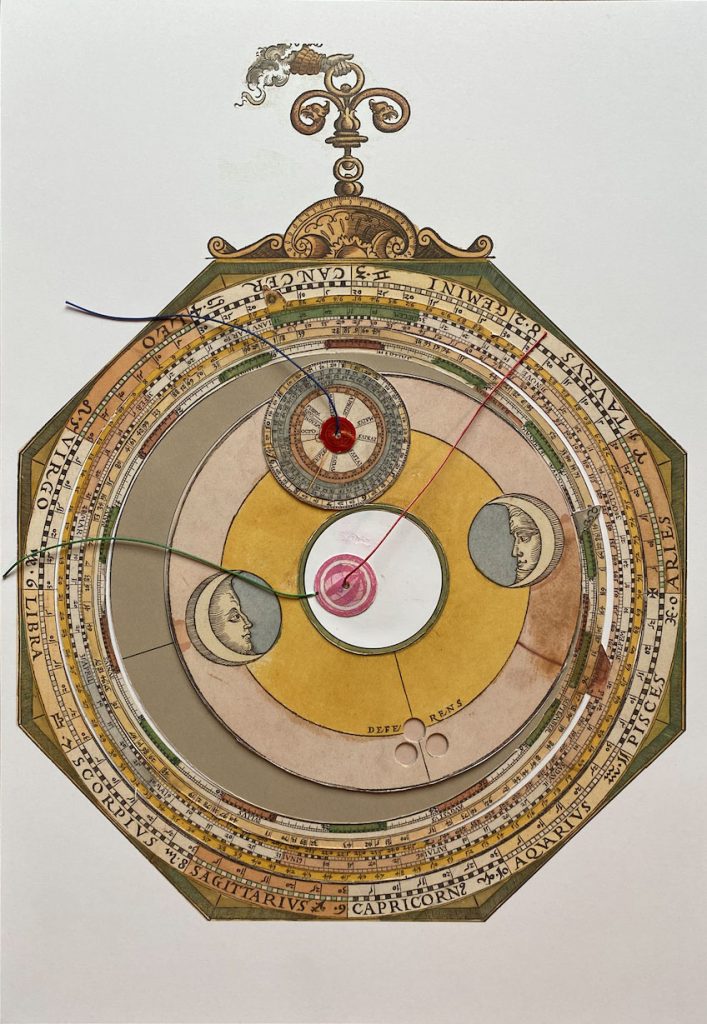

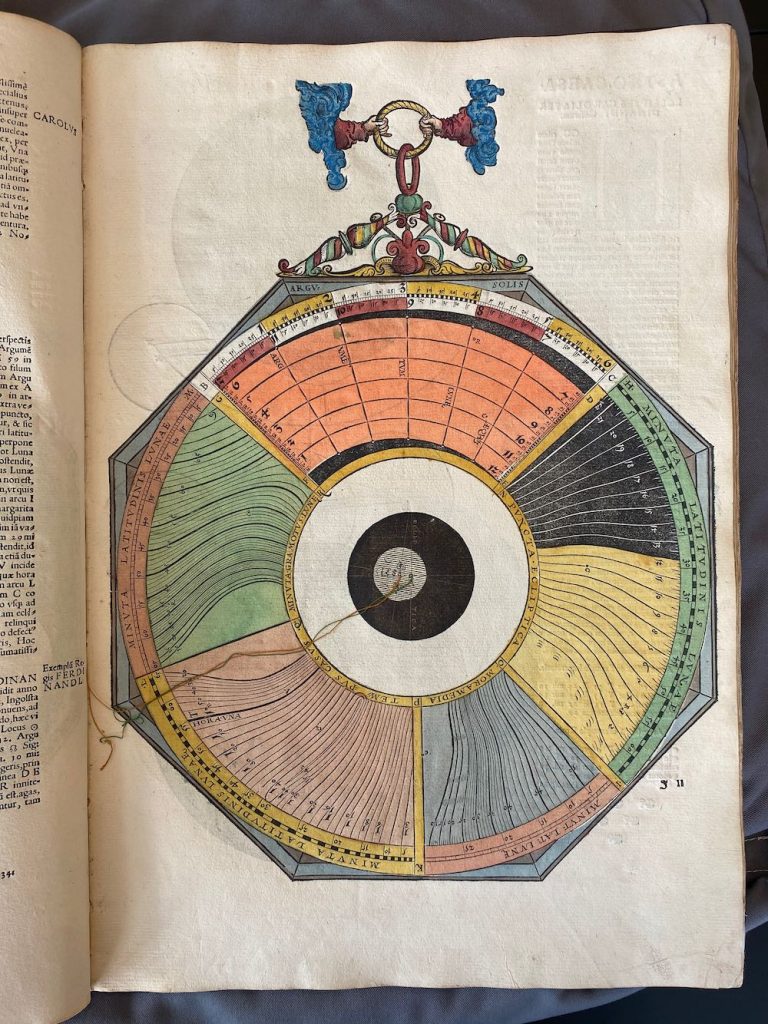

Nummer 14A – P43: Longitude of the moon Volvelle [7 lagen] >>> 14B [2 lagen]

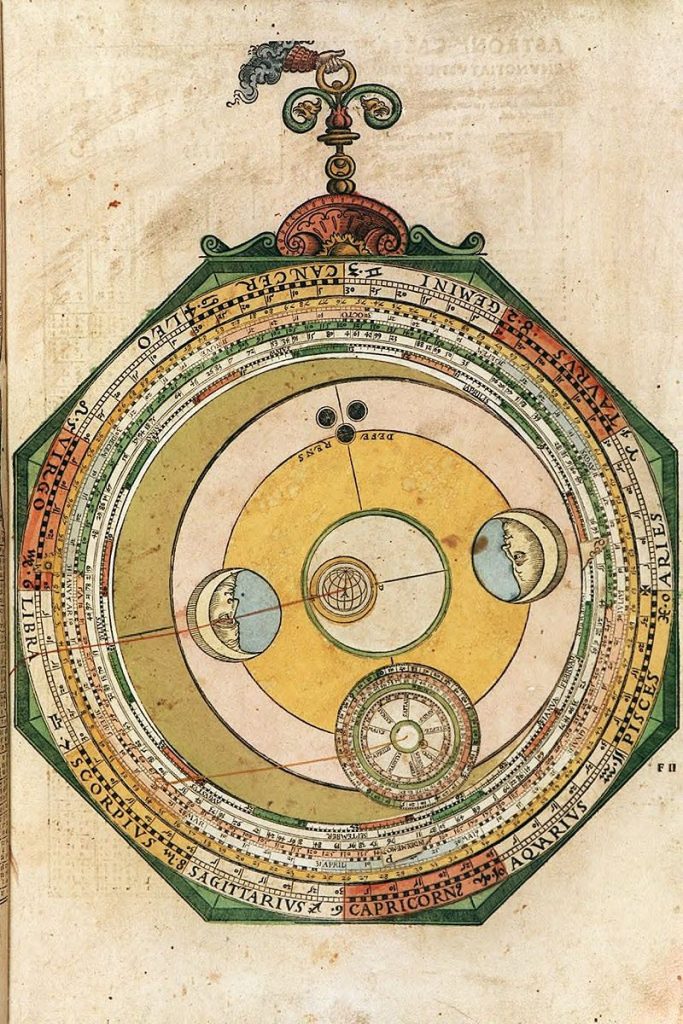

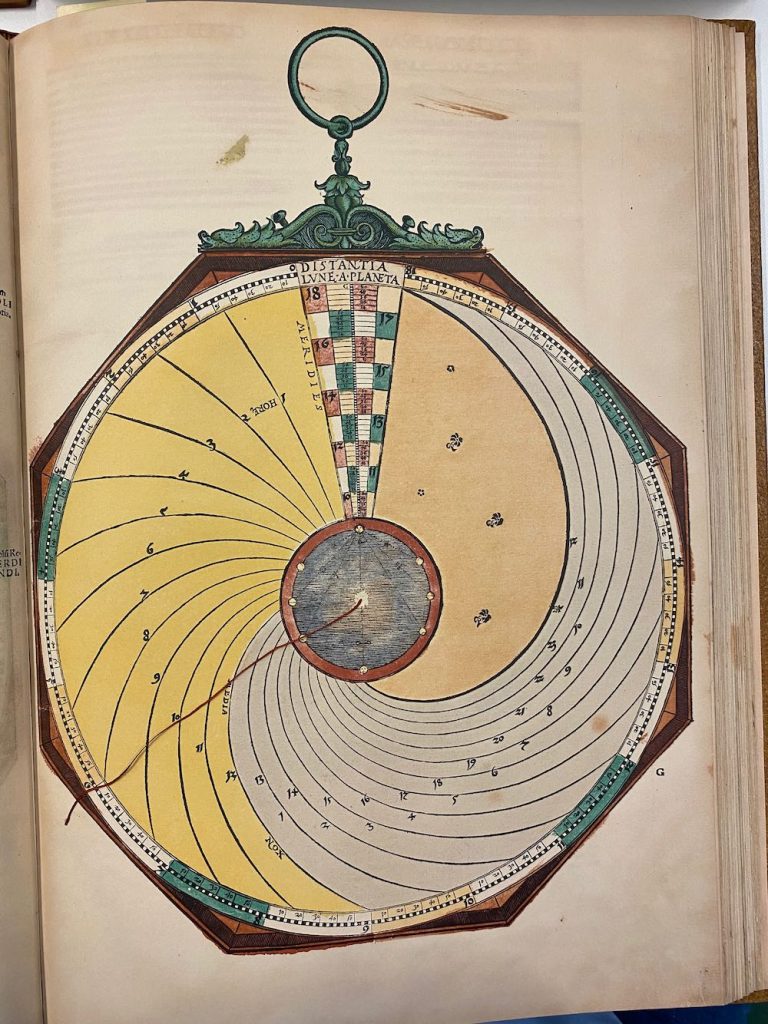

Nummer 15 – P45: The latitude of the moon [1 laag]

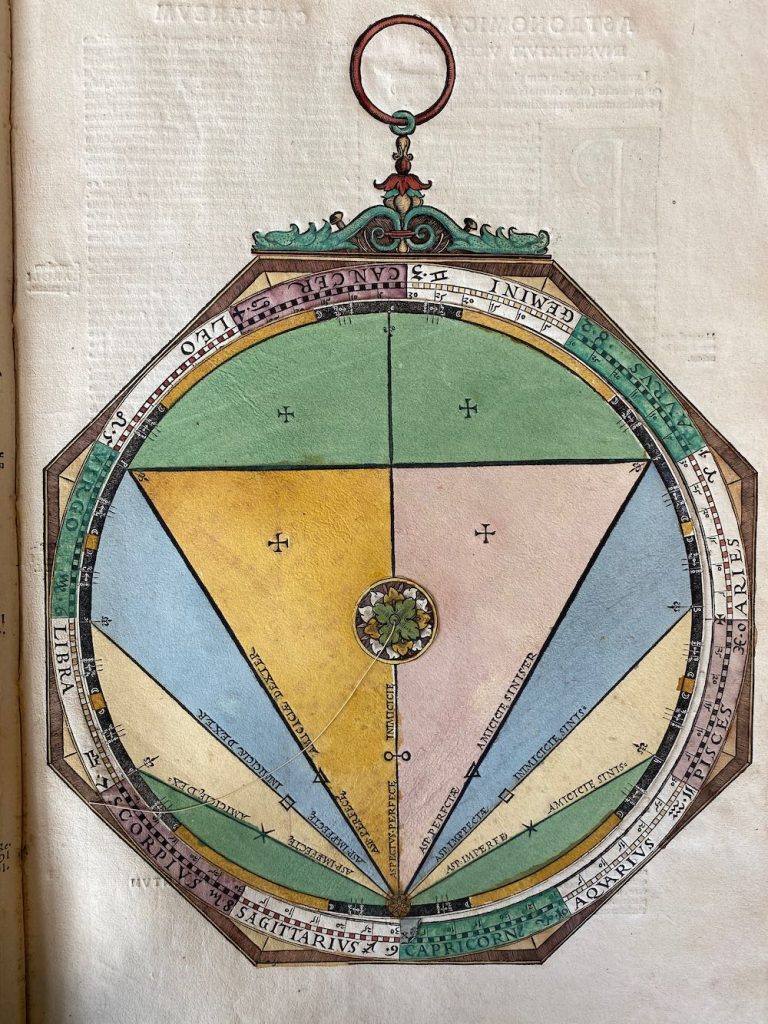

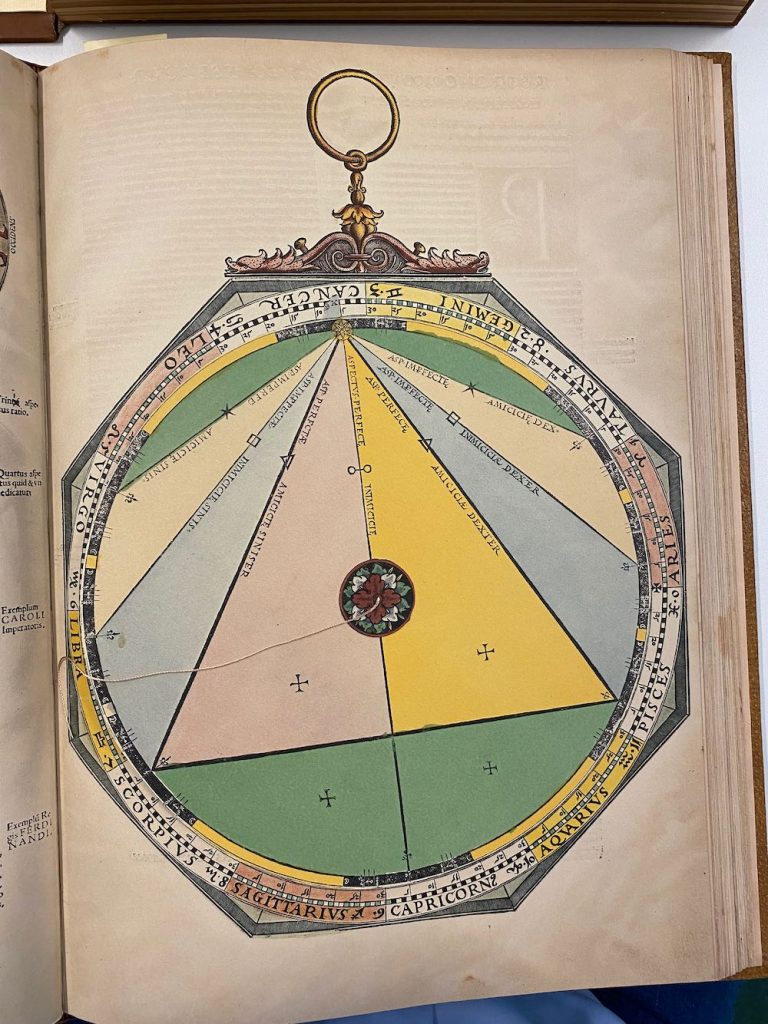

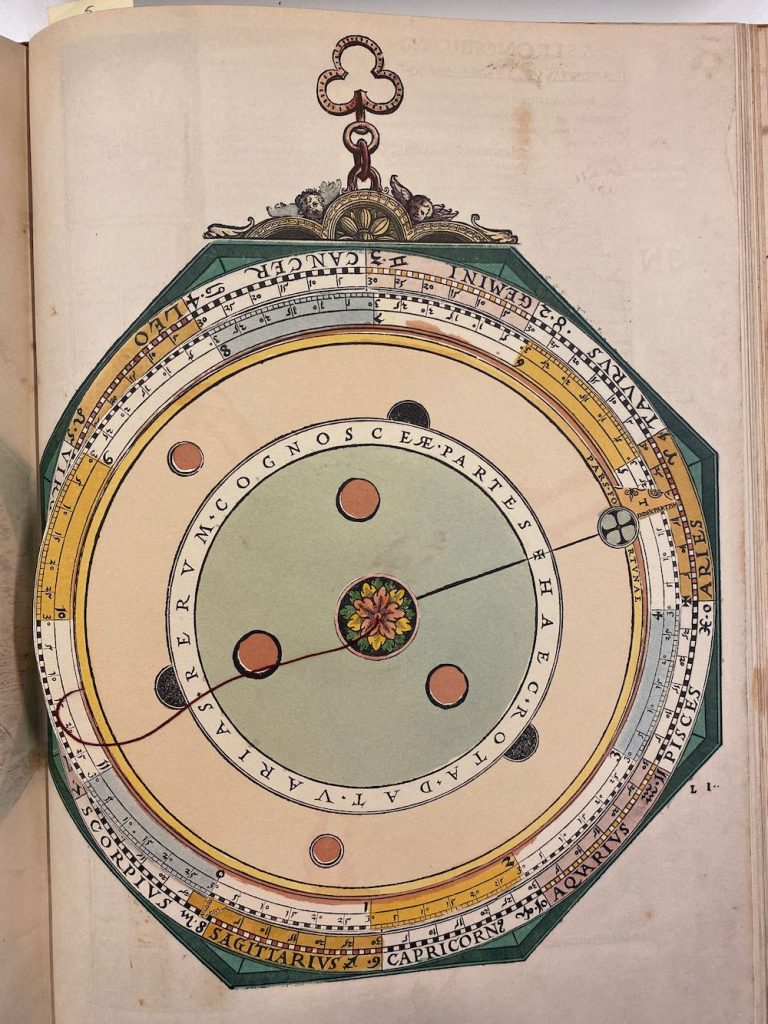

Nummer 16 – P47: The Planetary Aspects Volvelle [1 laag]

Nummer 17 – P49: Aspect time for the moon and a planet [geen lagen]

Nummer 18 – P51: Aspect time for two planets [geen lagen]

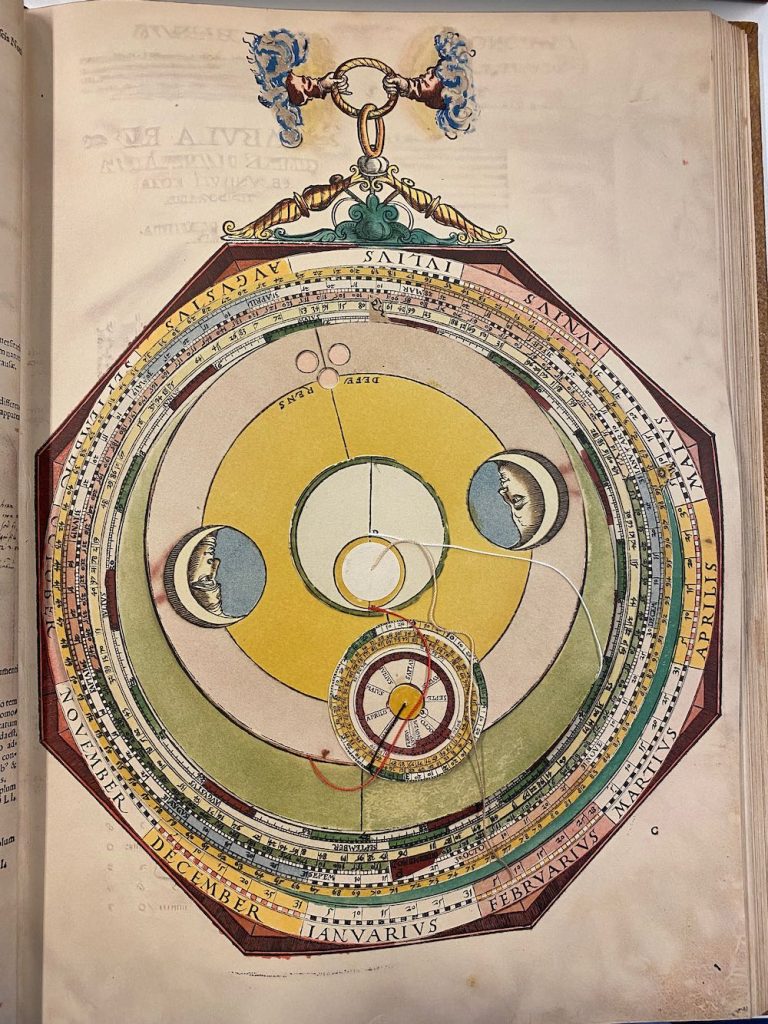

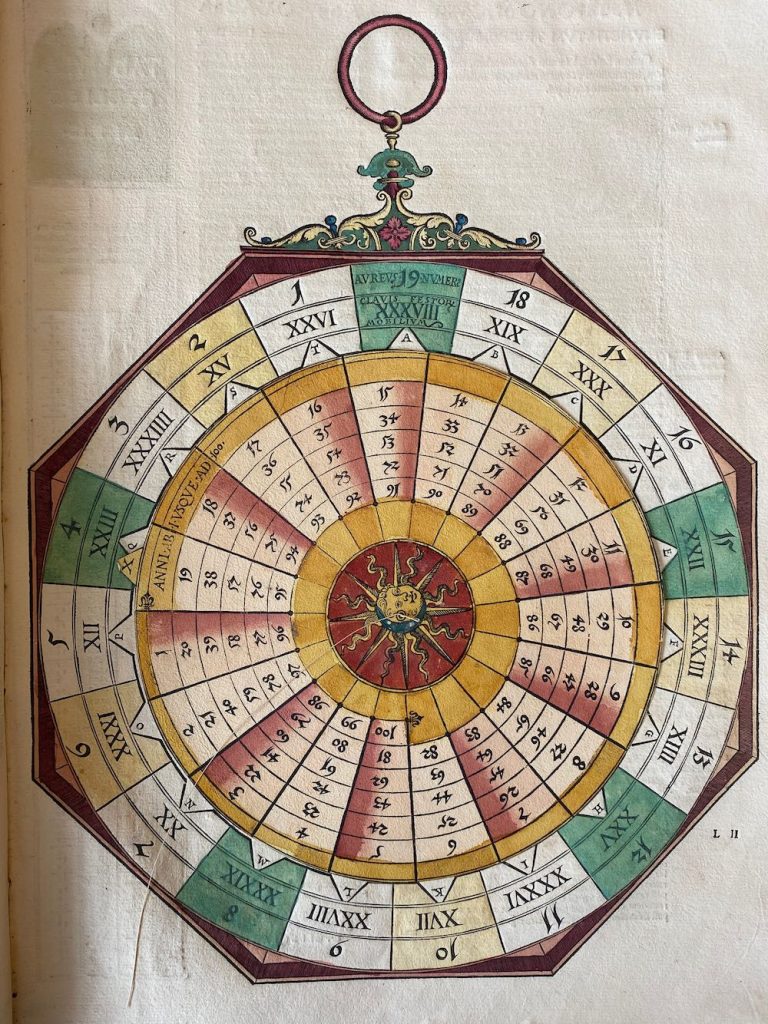

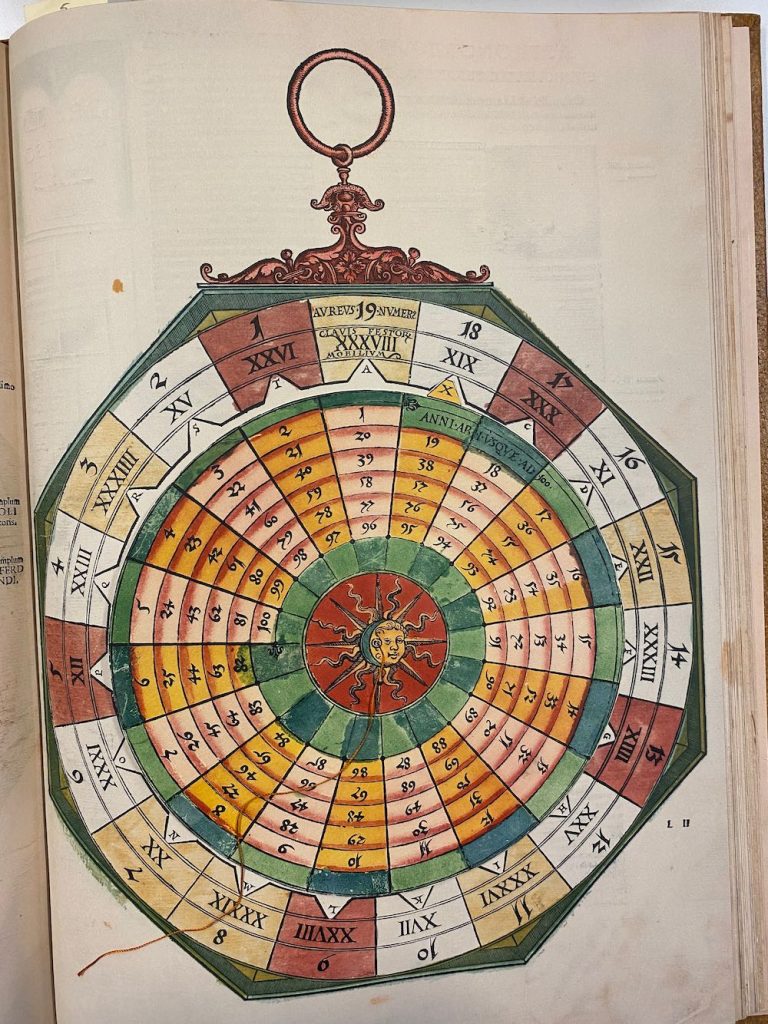

Nummer 19 – P54: Lunar Phases Volvelle [4 lagen]

Nummer 20 – P55: The volvelle for eclipse times [3 lagen]

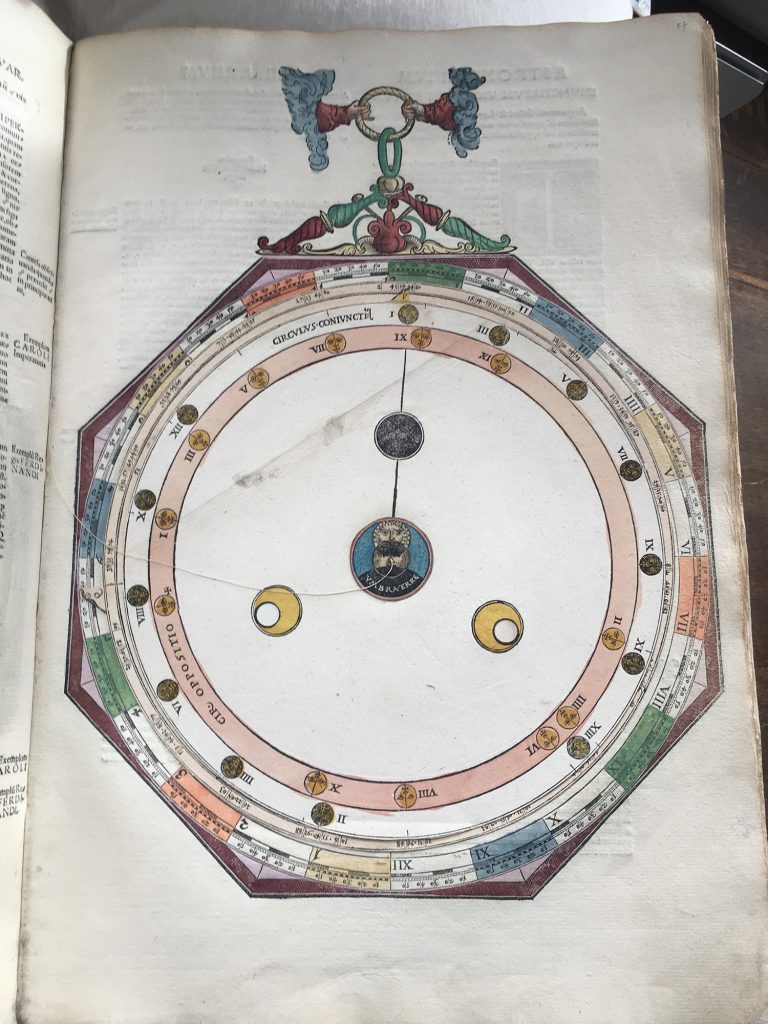

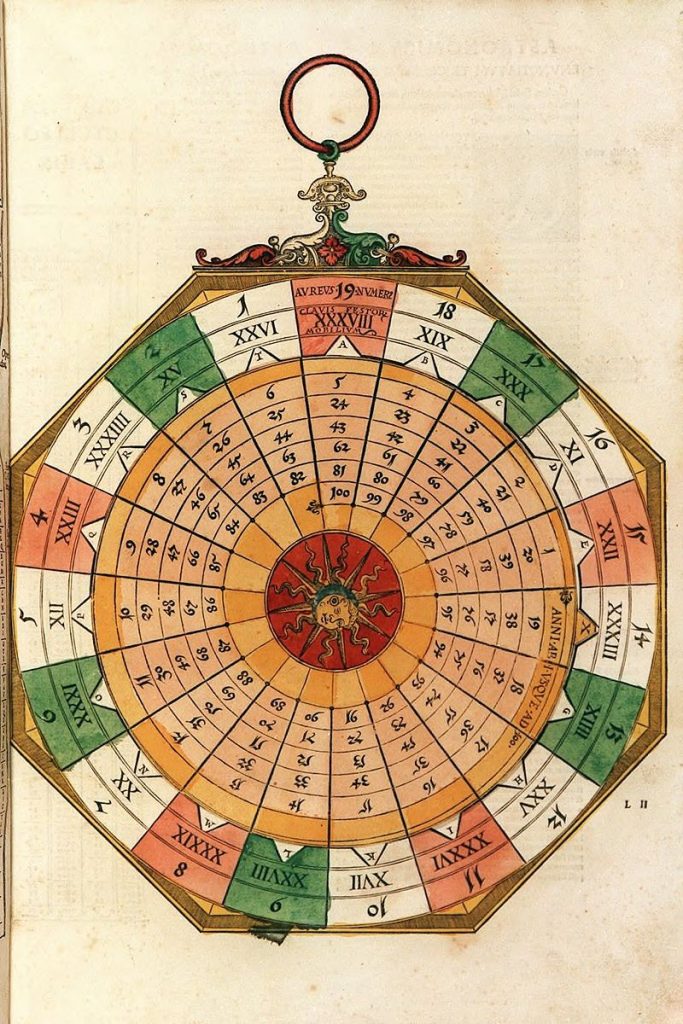

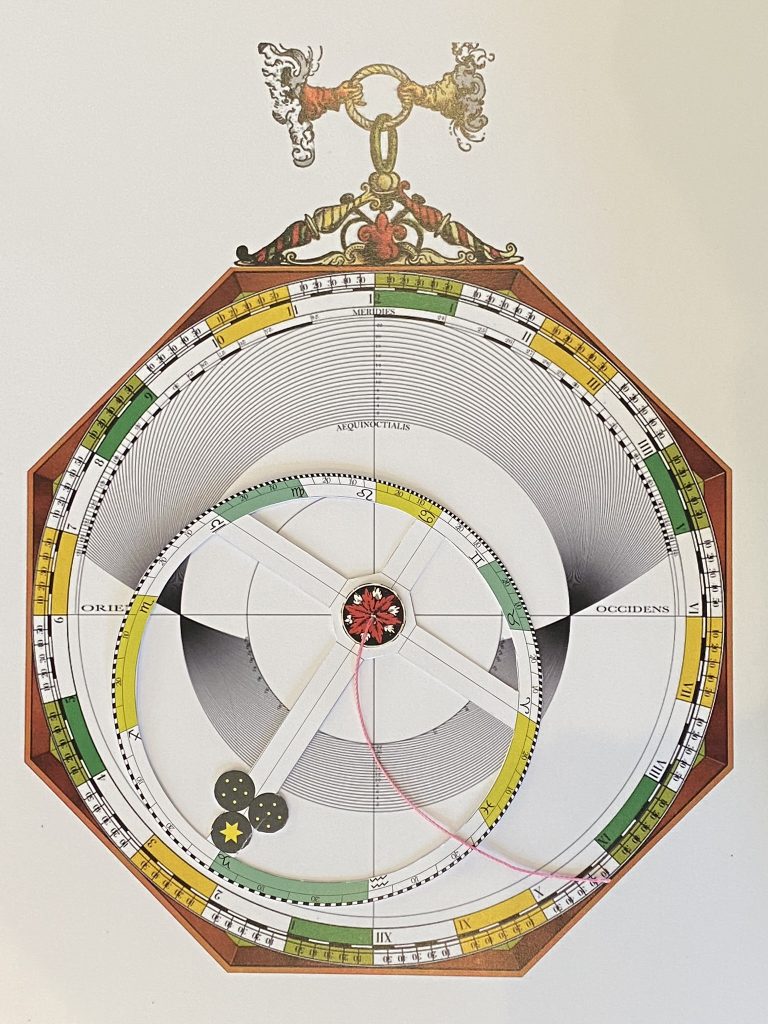

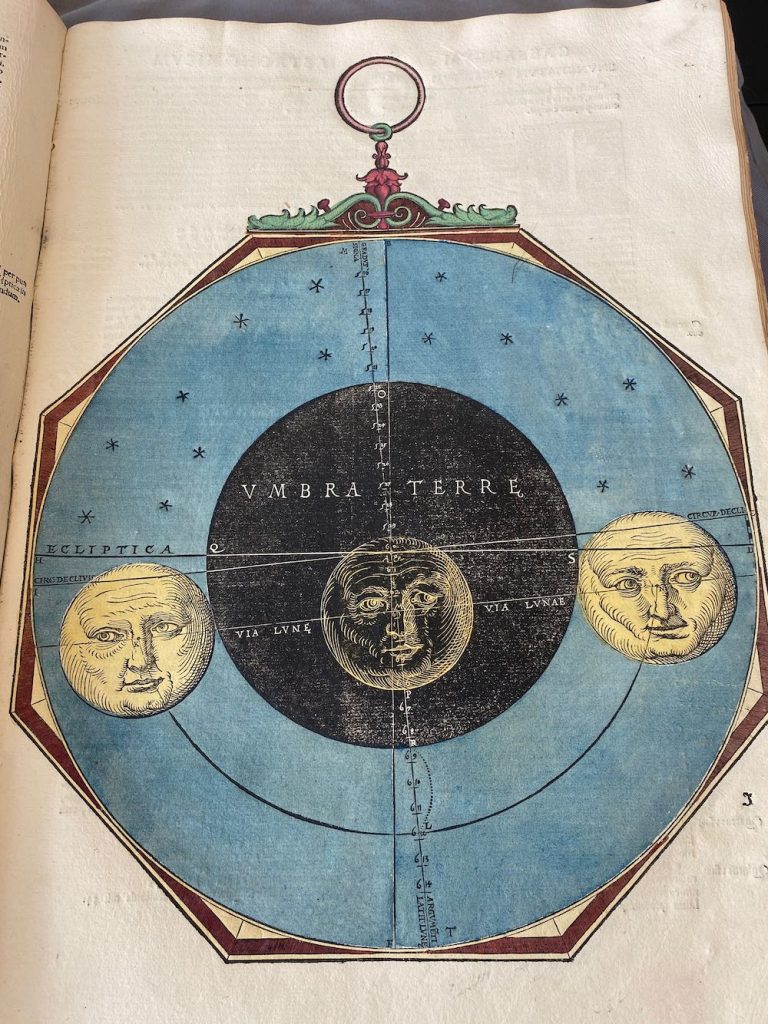

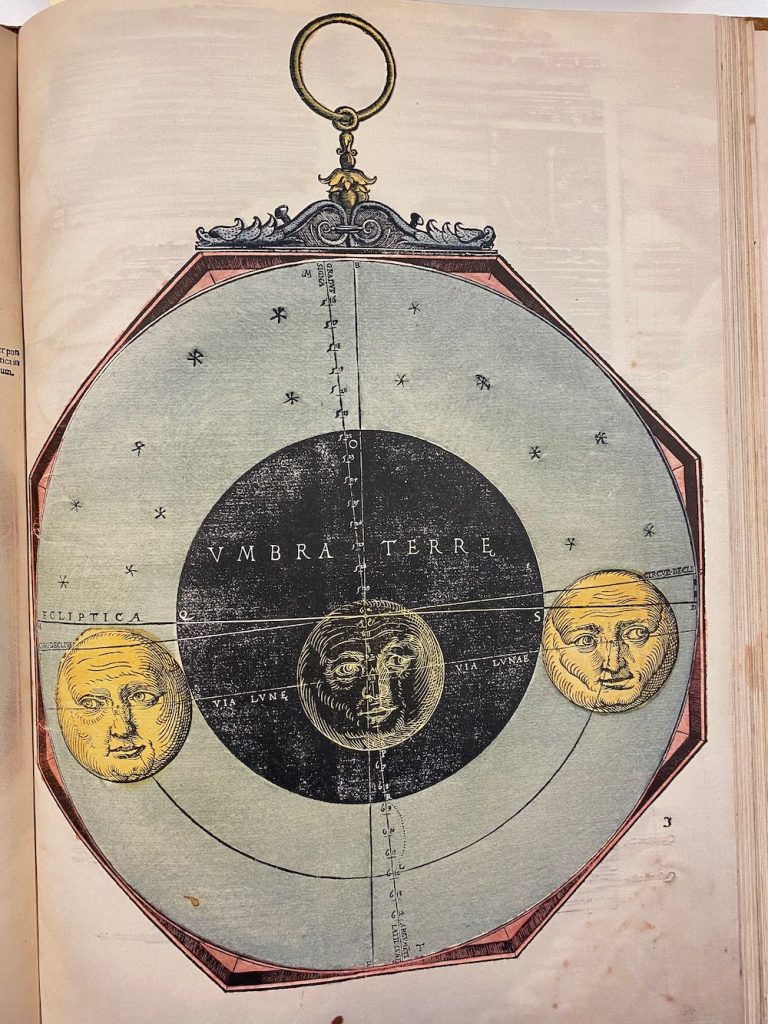

Nummer 21A – P57: The Volvelle for mean SyZyGy time [2 lagen] >>> 21B: [geen lagen]

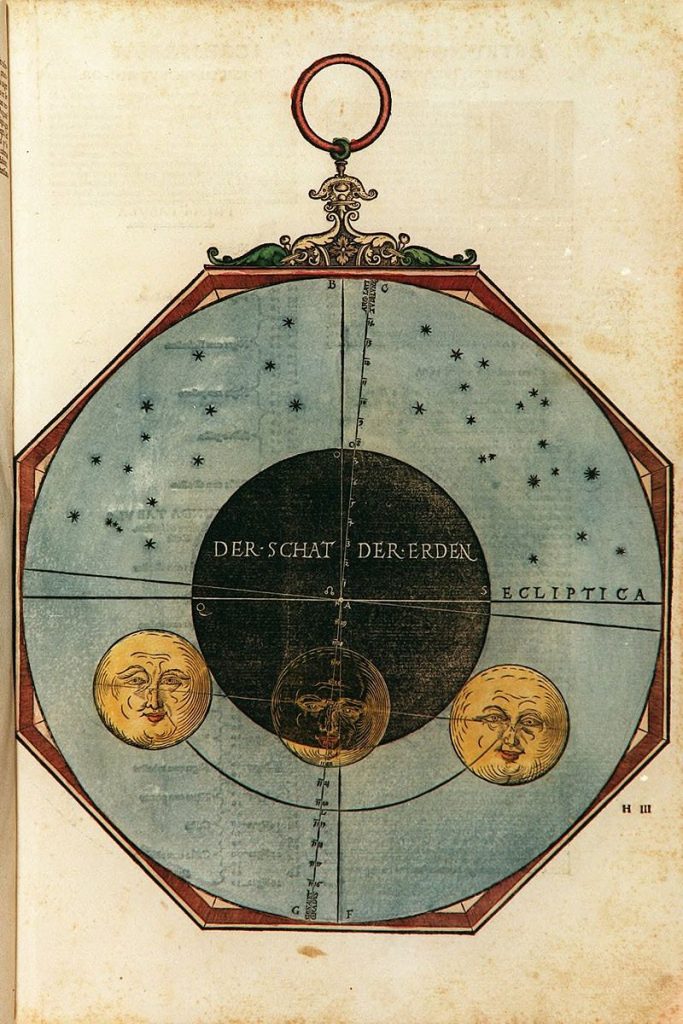

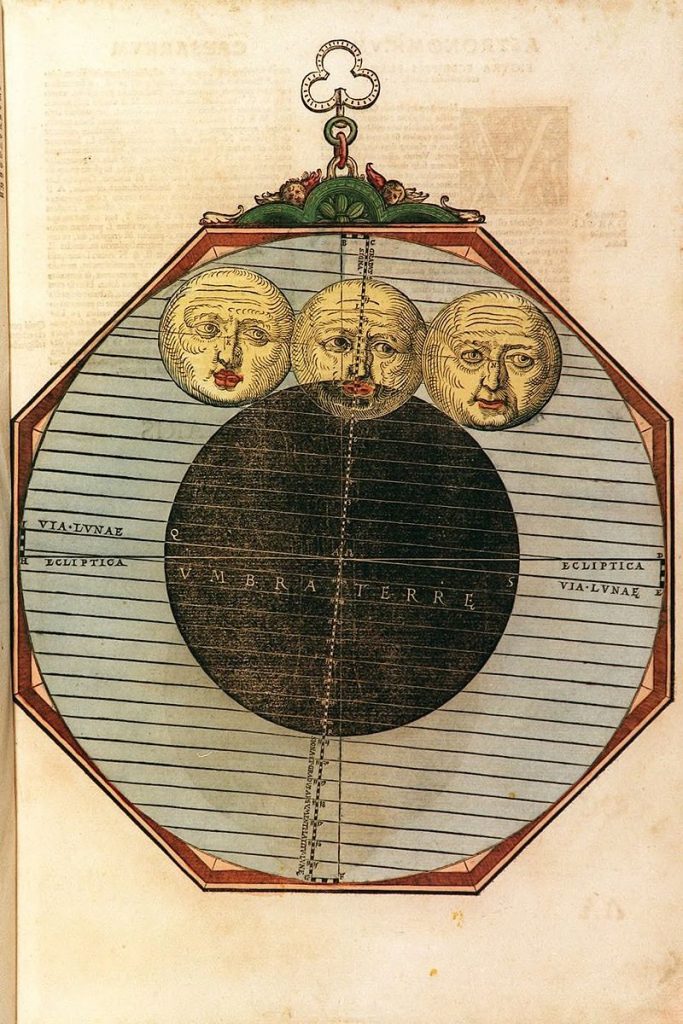

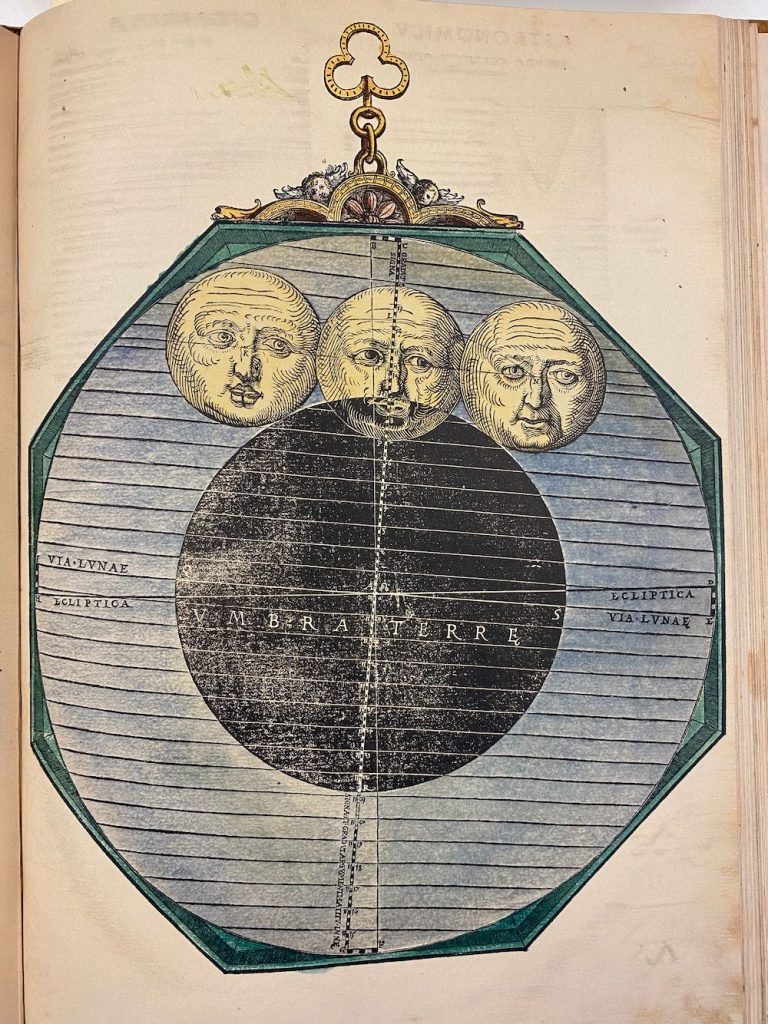

Nummer 22 – P59: Zon-, en maansverduistering [geen lagen]

Nummer 23 – P61: Zon-, en maansverduistering [geen lagen]

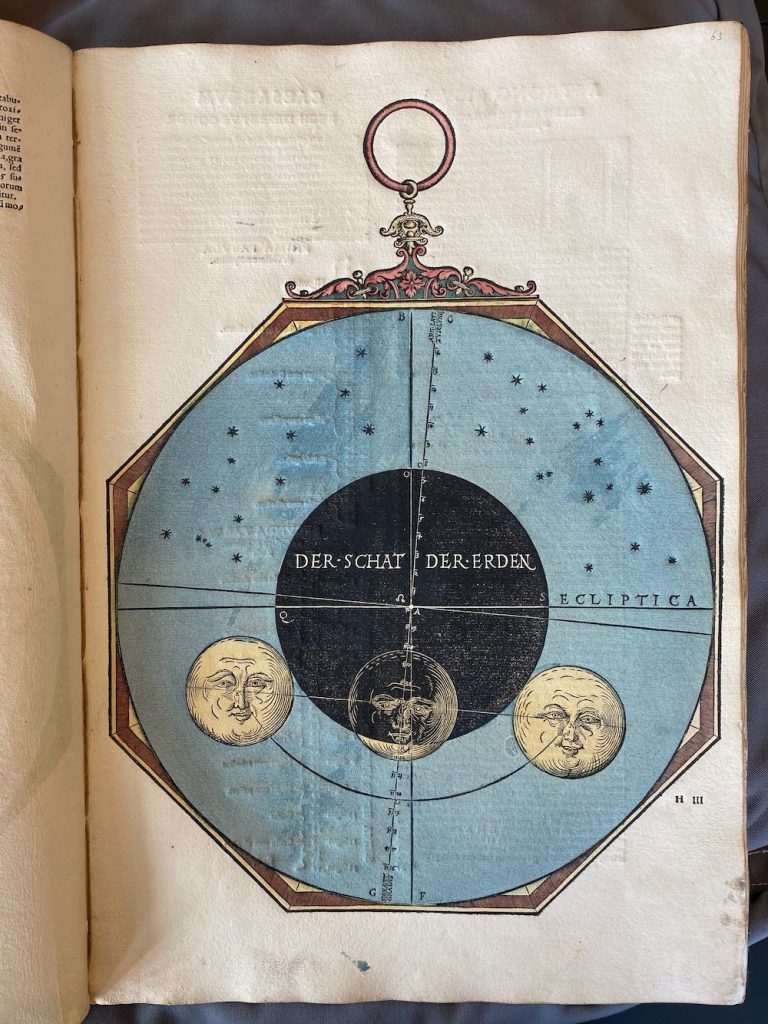

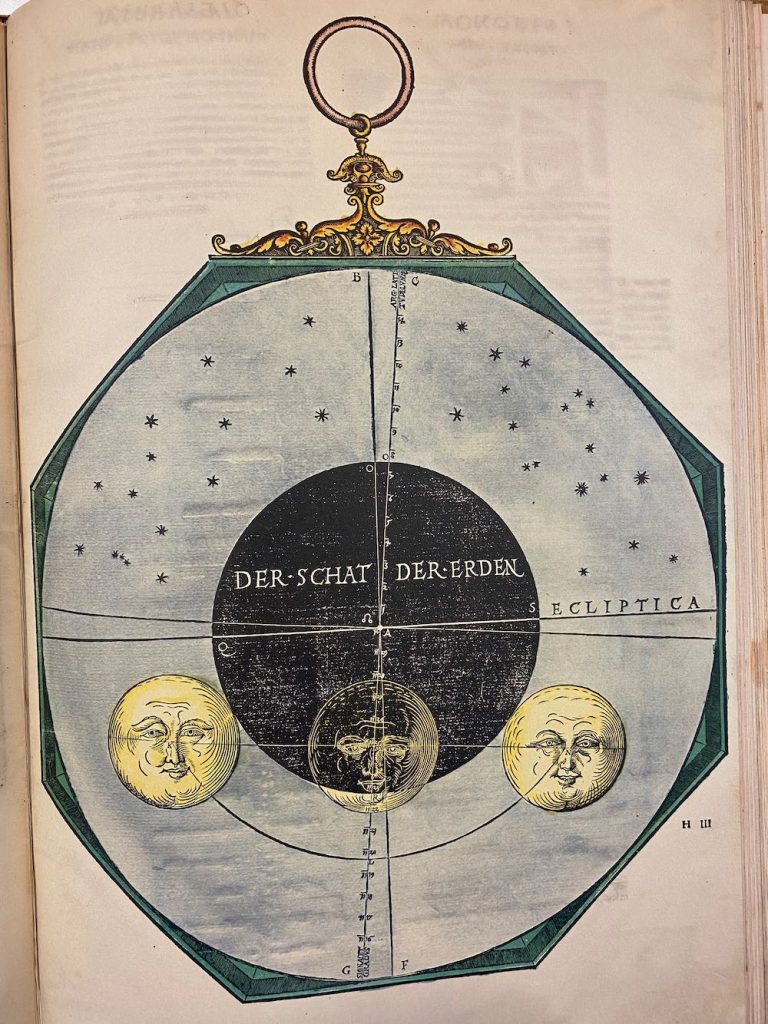

Nummer 24 – P63: Maansverduistering 1500 [geen lagen]

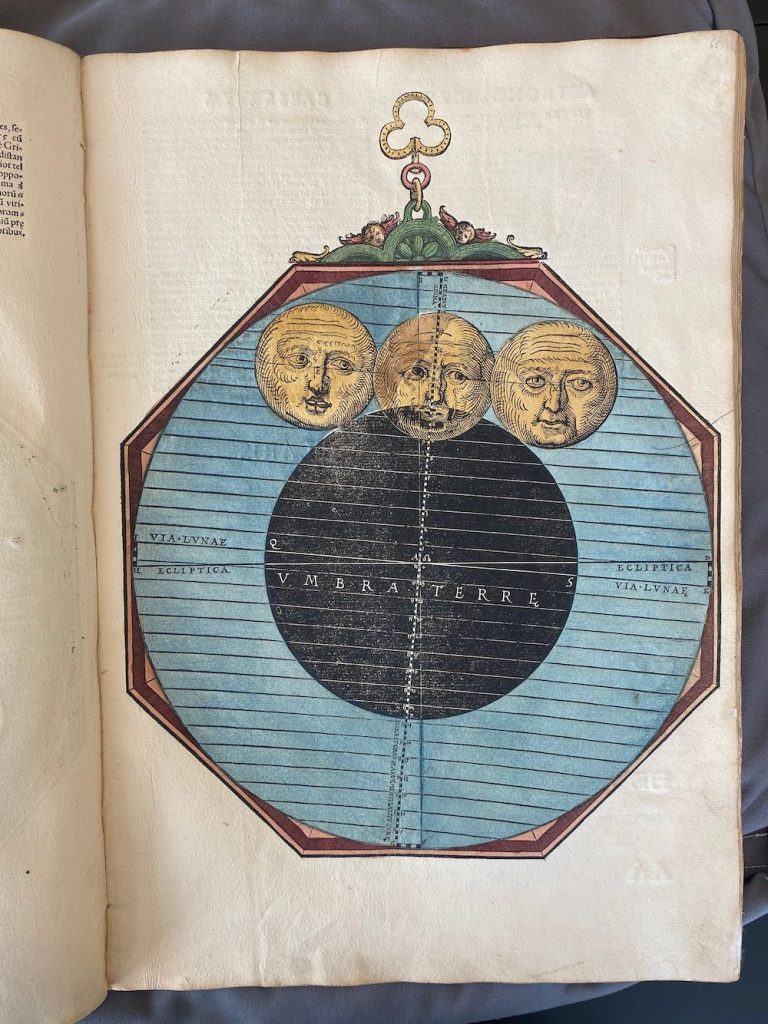

Nummer 25 – P65: Maansverduistering 1502 [geen lagen]

Nummer 26 – P67: Maansverduistering 1530 [geen lagen]

Nummer 27 – P69: Duur maansverduisteringen [geen lagen]

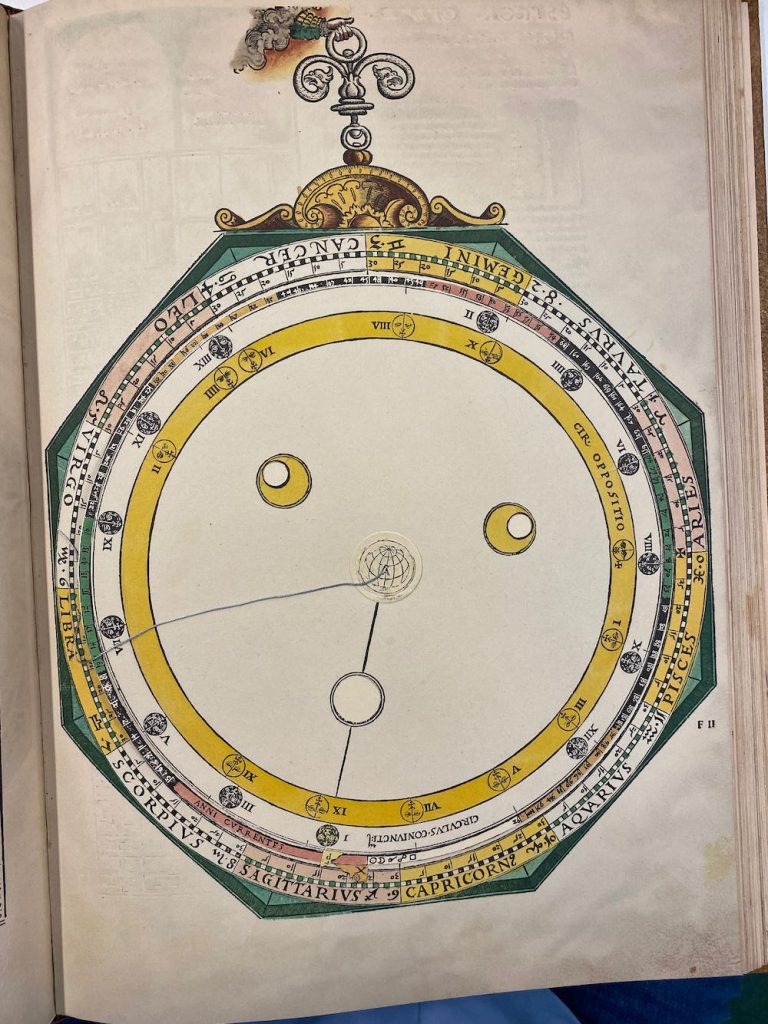

Nummer 28 – P79: Planetary Conjunctions [3 lagen]

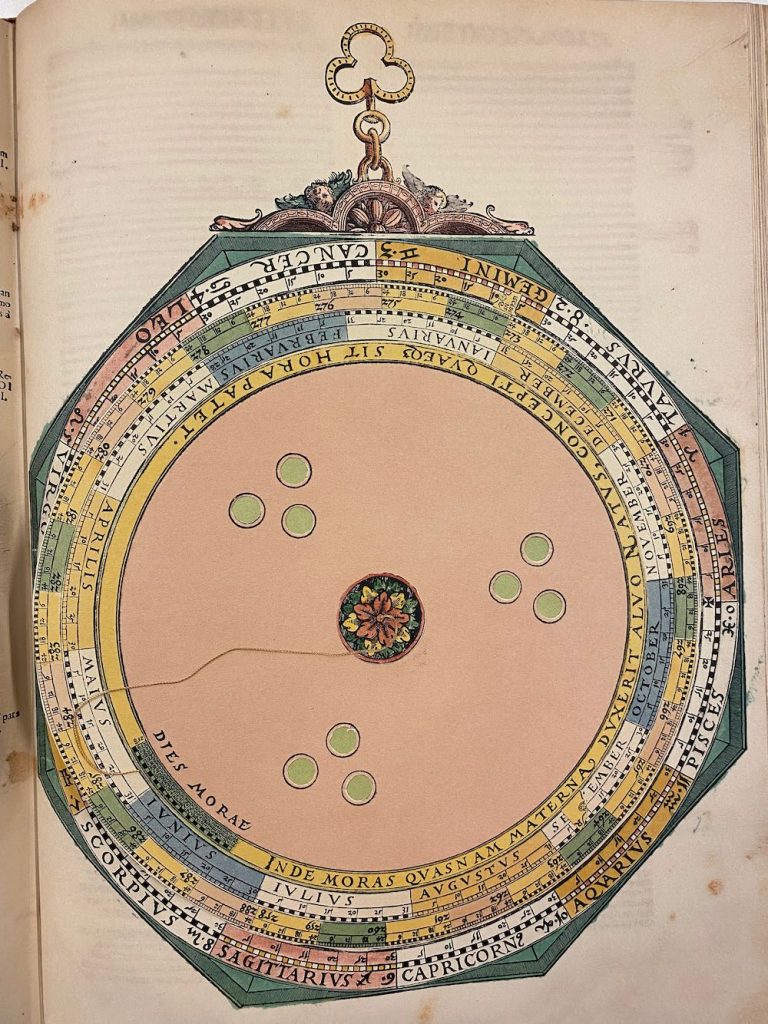

Nummer 29 – P81: Astrologie Geboorte [2 lagen]

Nummer 30 – P83: Astrologische huizen [2 lagen]

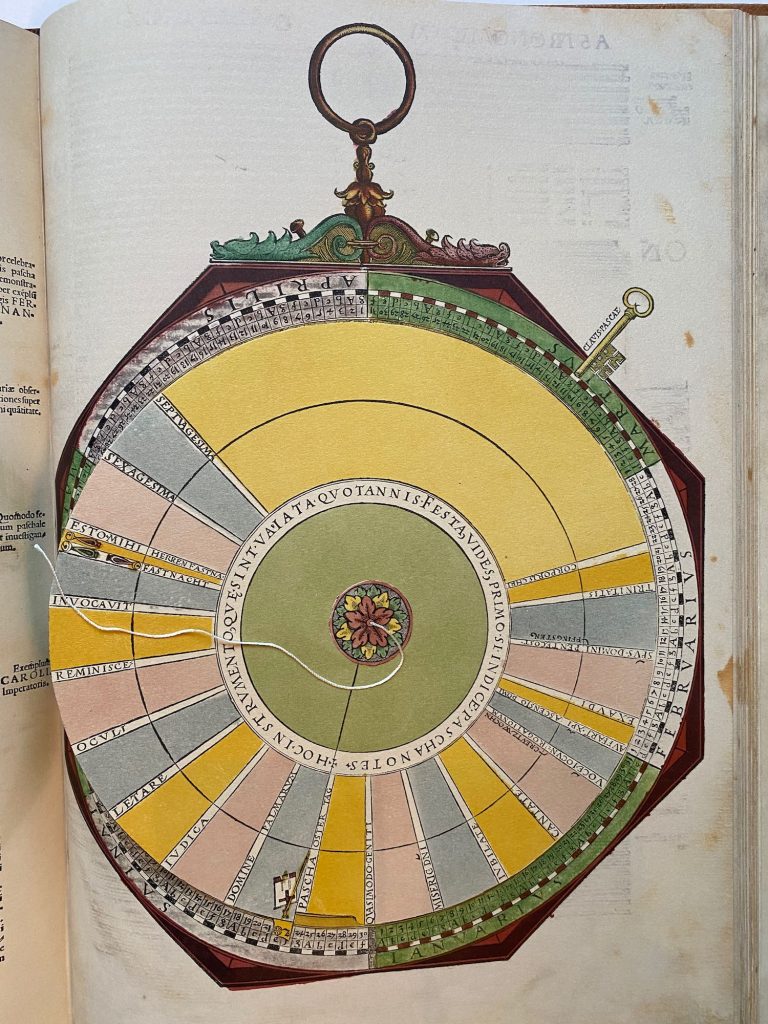

Nummer 31 – P85: Feestdagen kalender [1 laag]

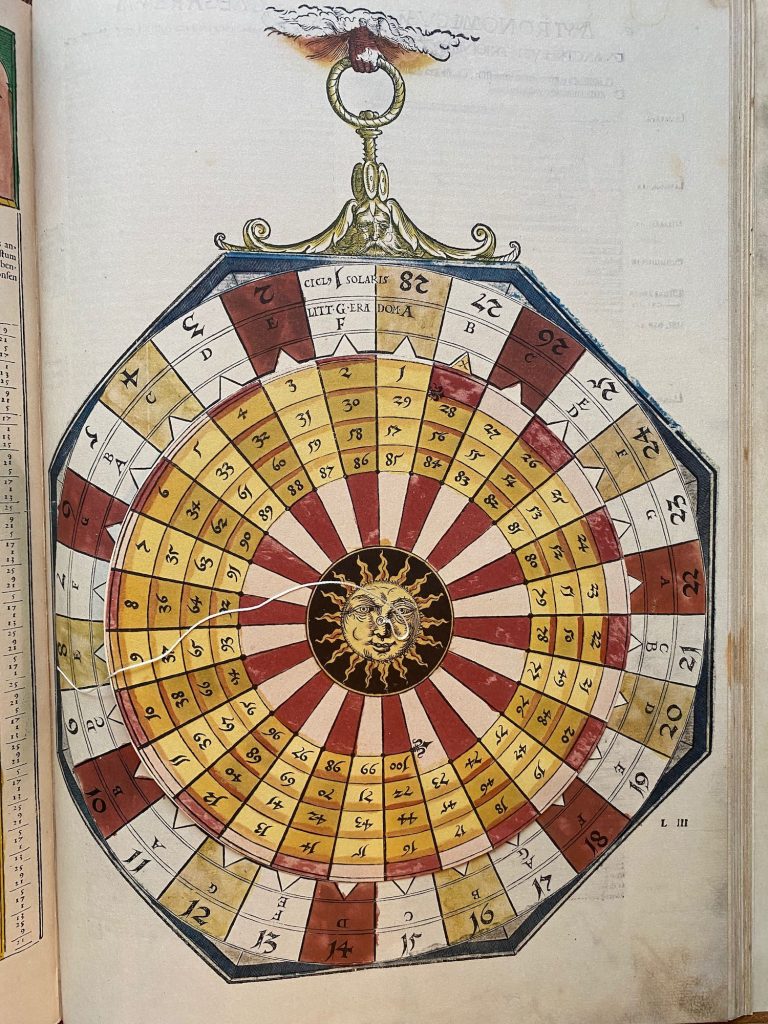

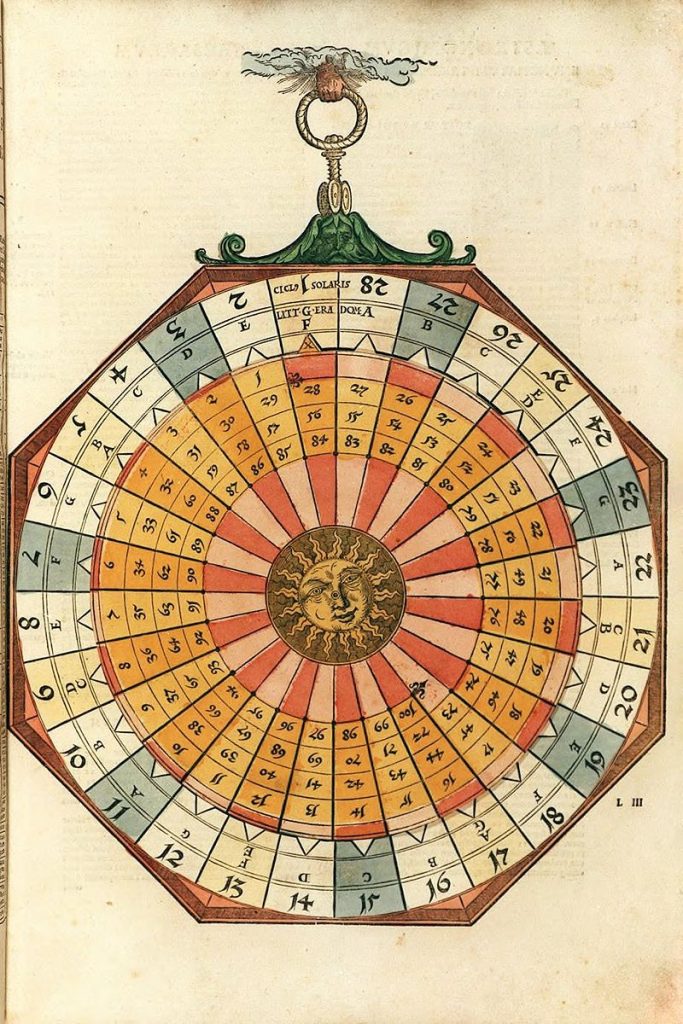

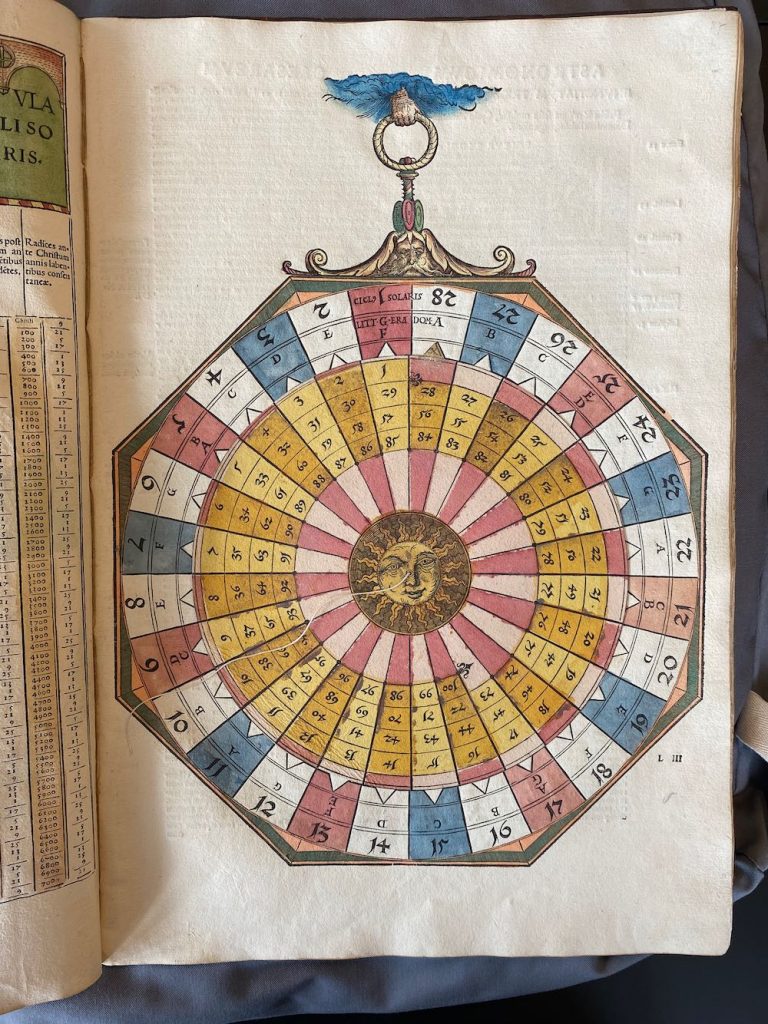

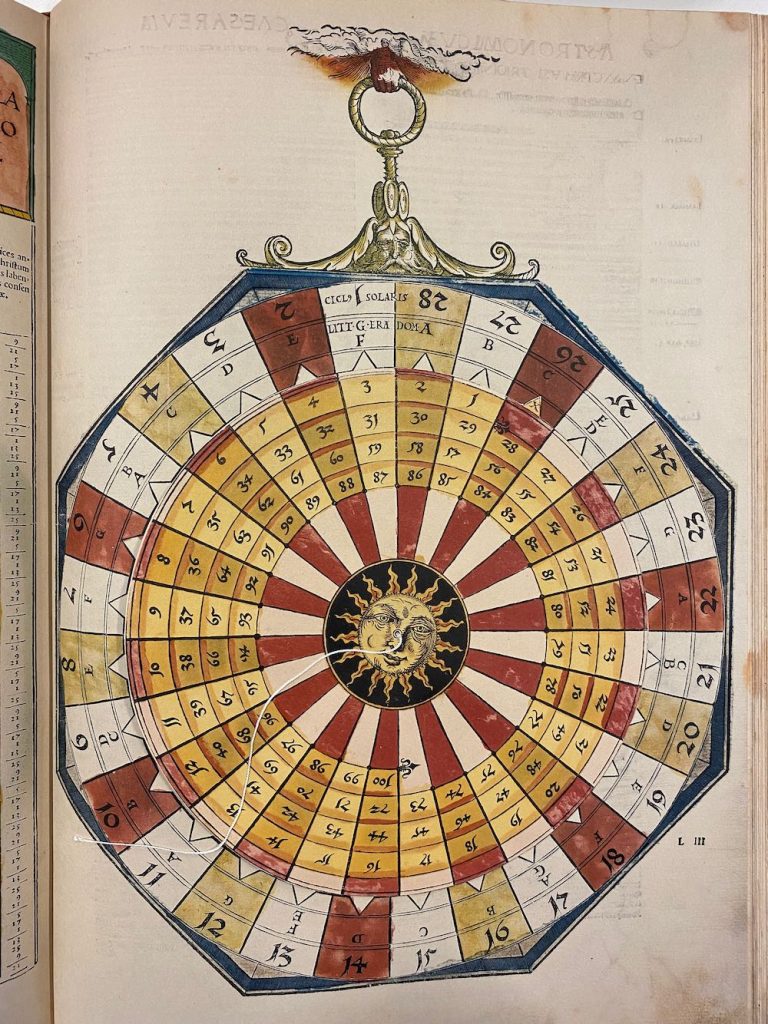

Nummer 32 – P87: Zonnecyclus [1 laag]

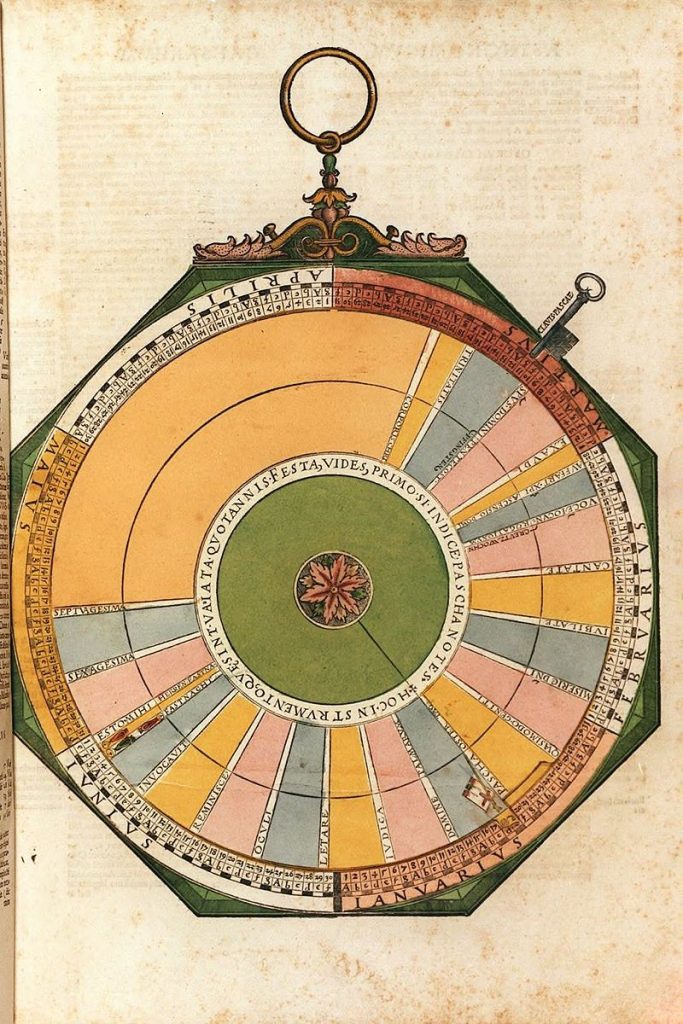

Nummer 33 – P89: Verplaatsbare feesten [1 laag]

Nummer 34 – P91: Equinoxen [1 laag]

Nummer 35 – P95: Astrology and Medicine Volvelle [1 laag]

Nummer 36 – P97: Naam onbekend [geen lagen]

Lars: ” This is shown in Figure 4. The mater has a circular scale divided into the twelve zodiacal signs, each sign being subdivided into 30°. On top of this is a circular disk, centred on the mater, with five index tabs for reading off the apogees of the planets and the Sun, Venus and the Sun having the same tab. There is a thread attached to the centre of the top disk. There is also a main index (marked AUX Communis) on this disk for setting the zero point of the fixed stars. The constant precession is set with a scale on the mater, hidden below the top disk and graduated from 7,000 BCE to 7,000 CE with a change of 7.3469° per millennium, the zero of the scale being at ecliptic longitude 0°. On the top disk, this precession is then corrected for the trepidation (varying between ±9°) by an elliptical scale using another tab marked X. The posit- ions of the apogee tabs, overlaid on Figure 4, agree well with the longitude values given in the Alfonsine Tables. I also calculated some values for the trepidation, and they also agree well with the points on the volvelle. In order to use the volvelle, align the central thread with the century value of the precession using the scale hidden under the top disk. Then move the main apogee index to the thread setting. Next, align the thread to the century value of the elliptical trepidation scale and move tab X to this setting. Finally, you read off the positions of the apogee tabs. These positions are used in the volvelles for computing the true longitudes of the planets.”

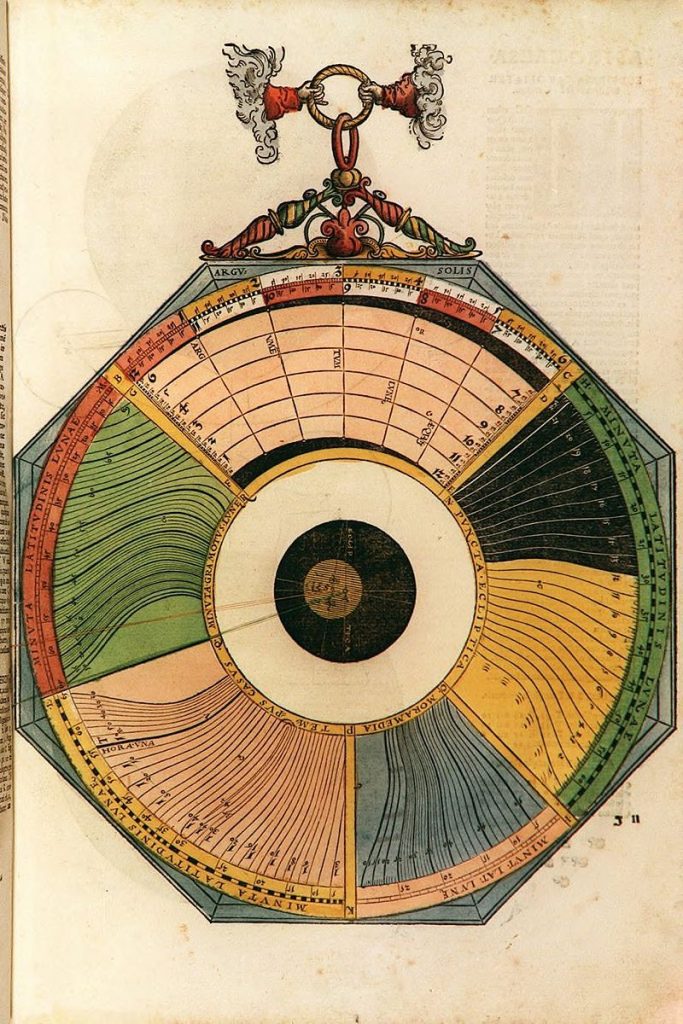

Lars: The mater (Figure 6) has a year scale with 365 days. There is a thread attached to the centre to read off the equation of time in minutes: seconds for a specific date. The equation of time differs from that in the Alfonsine Tables. The minimum is 0:0 on 1 February, first maxi- mum 20:56 on 9 May, second minimum 12:52 on 16 July and second maximum 32:48 on 23 October. Table 2 below shows a comparison with a modern calculation. The location of the maxima and minima fits rather well with a date in the first half of the sixteenth century although it is hard to draw any safe conclusions on the date of origin from the values in AC. The equation of time has a built-in addition of about 15 minutes in order to avoid negative numbers.”

2) Move all the layers on top of #2 to the now free mater #14. Except for the mater, this volvelle will now be in the correct place. This is the volvelle for the Moon’s longitude.

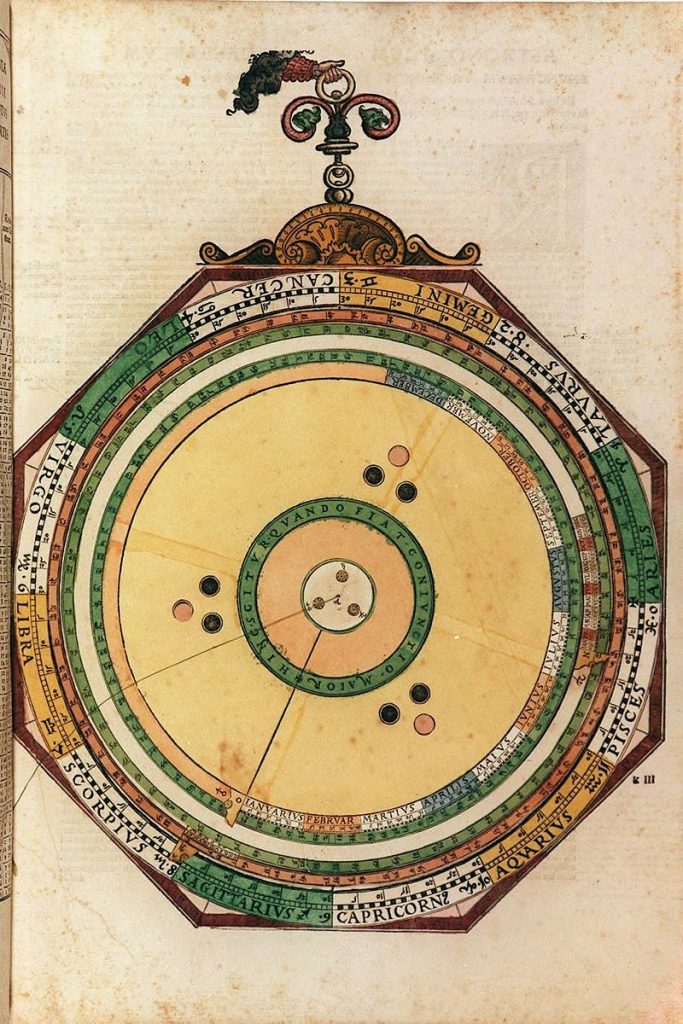

Lars: “The volvelle (Figure 8) is preceded by tables for the mean longitudes and arguments for each elapsed century before and after Christ. The unit in the tables is sign: degree: minute. I have checked the tables by recalculation. Table 3 shows the calculated tables for the century mean longitudes and arguments, and larger typographical errors, typically a couple of arc minutes, are marked in red. There are two tabular columns for each quantity, the left one (CE, Radices post Christum) for centuries after Christ, the right one (BCE, Radices ante Christum) for centuries be- fore Christ. The numbers in the tables are cal- culated using the 36,525 days in a Julian cen- tury and using the formula elapsed centuries · 36525 · daily motion + radix, and restricting the result to be in the interval 0° to 360°. The year within the century, the month, and the day are set on the volvelle as will be shown below. The layout of this volvelle is typical of those for the planets except for Mercury. The mater (Figure 9), representing the zodiac, is divided into signs and degrees. There are three axes, A, D, and E. D is located exactly in the middle between A and E. On top of the mater and centred with it on the main axis A, is a disk M, with an index tab marked M and the symbol of the planet, year marks for setting the year and a smaller scale for setting the month and day. The angles for the year marks are calculated by the formula (year· 365 + integer(year / 4)) · mean motion in longitude. The angles are reduced to lie in the interval 0° to 360°. The second term inside the bracket corrects for the extra days in leap years. Tables 4a and 4b show the result of a computer calcu- lation for years and months. Figure 10 shows the M disk with a comparison of the calculated year marks with the volvelle marks. On top of disk M is a circular disk (Figure 11), centred on the main axis A, with an index tab marked AUX and P and with the planet symbol for setting the position of the apogee, read from the sky volvelle. It has a circular scale with the axis D as centre. The scale is graduated with the zodiacal signs, each one sign being sub-graduated from 0° to 30°, however, the centre of the graduation is the axis E. From the edge of this scale there are slanting lines for each degree that connect with the periphery of the disk itself divided into 360 equal parts. On top of this disk P is a circular disk (Figure 12) mounted inside the circular scale of disk P, its axis coinciding with the axis D on the P disk. This is the deferent disk, it is marked with a circle DEFERENS and the name of the planet. On the periphery of this circle, at point F, there is another disk attached (Figure 13), the epi- cycle base disk. It has a 360° graduation anti- clockwise around its periphery with a cross mark- ing the origin. On top of, and centred with the epicycle base disk, is the argument disk Y (Fig- ure 14) with an index tab marked Y and a sequence of year, month and day marks for setting the argument for the year and date. There is a ‘star’ symbol showing the position of the planet on the epicycle; in the case of Mars, Venus and Mercury it is positioned on the periphery of the disk on the Y tab, and in the case of Jupiter and Saturn on a circle with a smaller radius. There is a thread attached to the centre of the Y disk. The marks on disk Y are calculated using the same formula as for the longitude, but using instead the mean motion in argument and the argument radix. Table 5 shows the result of a calculation, and Figure 15 shows the actual Sat- urn Y disk with a comparison of the calculated year marks with the volvelle. Finally, there is a cap (Figure 16) covering the centre of the deferent disk. It is marked with letters E – Equans, D – Deferens, and A – Mundi. There are threads attached to the points E and A. The distance between points A and D and D and E is the eccentricity of the planet. For the working of the volvelle I give a slight- ly redacted English translation f om pian ’ Ge – man manual:

If you want to find the positions of Saturn, Jupiter or Mars, where they are in the zod- iac, then look carefully at this example. There is a well-known person [i.e. Charles V], born 1500 years after the birth of Christ on 23 February 15:44 hours after noon. In chapter 3 I have reduced this time to the meridian of Ingoldstadt to 16:23 hours. I have also corrected it for the unequal days (equation of time) in the next volvelle to 16:23:4 hours. This is the correct time on which to find the positions of the stars. As the birth was on 23 February, you understand that the year 1500 was not fully elapsed and that you therefore have to use the previous year that is elapsed and take 1499 and find the positions for this year. Search in the table of numbers, under the section Tabula Medii Motus Saturni (what I tell you about Saturn is the same for Jupiter and Mars) in the first column to the left, the year 1400, where the header says Radices Post Christum (the radix for the middle move- ment in longitude after the birth of Christ) there it is written as Capricorn 12:38. Then search by the year 1400 under the section Medii Argument Saturni and under the col- umn Radices Post Christum, and you will find the century radix as 0,5;56. Fo hi example yo don’ need more from the tables. Search the radix Capricorn 12;38 in the zodiac or mater scale of the volvelle and set the index tab M to it. There are 99 more elapsed years after 1400, and you must search for that year in the circular scale of disk M, you will find it close to Taurus 23°. Stretch thread A to that year and move tab M under the thread. You will also see a calendar on this disk close to tab M where each month is marked by a letter: January by J, February by F, March by M and so on. Each month is divided into six divisions, each one corresponding to five days but you have to note that the last div- ision corresponds to six days in January, March, May, July, August, October, and De- cember, and five days in April, June, Sep- tember and November. In February the last division corresponds to three days for an ordinary year and four days for a leap year. Jupiter has the same graduation, but Mars has a finer graduation, each division corre- sponds to one day. When you have examin- ed the calendar you need to find the day of this birth, 23 February (the 16:23 hours are not necessary because of the coarse gradu- ation of the calendar). Stretch again the thread A to this date and again move tab M there. This disk is now set correctly. In chapter 4, you found that the longitude of the apogee of Saturn in 1500 was Sagittarius13:10. As this year is not elapsed we decrease the value by 1′. Set index tab P on the P disk to the value Sagittarius13:9 on the zodiac scale of the mater and this disk also is set correctly for the birth. Now you also have to set the deferent disk and the epicycle disks correctly for this hour of birth. Therefore search on the bottom epicycle disk, on which there is a cross marked, the radix for the mean argument, 0,5;56 and move index tab Y to that position. Search for the extra 99 years on the top disk (you will find it close to sign number 8 on the lower disk) and stretch the thread from the epicycle centre to it and move tab Y there, keep the disks locked and finally stretch the thread to 23 February 16 hours (you can skip the minutes) and move again the top disk with tab Y there and you have the epicycle disks correctly set. Further, you have to look for where the index tab M touches the peripheral P disk scale, that happens in 5,12;30. This location is called the mean centrum. Go from this point on the periphery of the P disk along the slanting line on the disk until it meets the scale of the disk and stretch thread E to it, that is from the centre of the equant to this point, and move the deferent (on which the epicycle is) with the epicycle centre under this thread, and align the cross of the bottom epicycle disk to be under the thread, directed outwards to the mater and not inwards to the centre of the instrument, then you have set up the instrument correctly. Then, if you align the tread from A in the centre (where Mundi is written) with the centre point of the star, not far from the centre of the epicycle disk, then it shows Taurus 17:40 on the scale of the mater. That is the true position of Saturn that you have requested for this birth. If you then want to find the true cen- trum of Saturn, by which you can later find the latitude of Saturn in the ecliptic, then stretch thread A from the centre, through the centre of the epicycle disk and it hits the P disk scale in 5,10;20, that is called the true and equalled centrum. You can also find the true and equalled argument of Saturn. When you have stretched thread A through the centre of the epicycle disk, note where the thread crosses the scale of the bottom epicycle disk, the same point is the most distant point of the epicycle from the Earth, or the whole world, that is from centre A. It is called the true apogee by the astronomers. From the same point, the angle to tab Y is the true argument of Saturn, 9,17;52. That number is necessary to have when you later search for the latitude of Saturn in the lati- tude volvelle.”

Lars: “This volvelle (Figure 17) is constructed and works exactly as for Saturn. Table 6 shows the calculated century longitudes and arguments. Tables 7 and 8 show calculated year marks and Figures 18 and 19 comparisons with the volvelle marks.”

Lars: “This volvelle (Figure 20) also is constructed and works exactly as for Saturn but uses the para- meters of Mars (see Tables 9‒11 and Figure 21). On the epicycle disk of Mars, the argument mark for year 94 is grossly misplaced, it should be close to the year 15 mark in the lower right of Figure 22.”

Lars: “For the Sun the working is that you take the century mean longitude from the table corrected for the individual year and set tab M to that value. Tab M is then corrected for the date and hour, using the months and day scales. Tab P on the top disk is set to the longitude of the apogee. The slanting lines are followed from tab M to the scale on the top disk and the thread from the centre is aligned with that point and followed back out to the zodiac scale of the mater where the true longitude is read.”

Lars: “The Ptolemaic model for Venus is identical with that for the outer planets (see Figure 24). The mean motion in longitude is the same as for the Sun and is marked and set in the same way using tab M marked with symbol for the Sun, Venus, and Mercury. On the page preceding the volvelle is a table (Table 13) for the century arguments.”

Lars: “The Mercury volvelle is shown in Figure 26. The Ptolemaic model for Mercury is quite involved (Figure 27). In addition to the ordinary epicycle the centre C of the epicycle and the deferent is dragged clockwise by a crank system around a small circle with the radius of the eccentricity and centred on D. The position of the mean centrum is the angle BEC, and the crank angle BHK is equal to this angle. The argument is the angle FCP as before and the true argument is the angle GCP. Finally, the location of the true centrum is the angle BAP. The mean motion in longitude is the same as for the Sun and is marked and set in the same way. The Mercury volvelle has a more compli- cated structure than the other planetary volvel- les. On top of the mater and centred on it is disk with an index M and symbols of the Sun, Venus, and Mercury for setting the mean longitude. It has a year scale to set the date with index M once the solar radix of the year has been set. On top of this disk is the P disk for setting the apogee. It has a set of slating lines, one for each degree that connects the periphery of the disk with an inner zodiacal scale, offset from the main axis in the same ways as for the other planets and graduated clockwise and starting from index P. Along the periphery, the slanting lines are graduated anti-clockwise also with a zodiacal scale and starting from P. This scale is used to measure the elongation of the mean longitude from the apogee, i.e. the mean centrum. On top of disk P is another disk with an index tab Q and on top of this disk is the deferent disk. The axis of deferent disk is made to rotate around a centre H in a small circle (Parui Cir:) that is at- tached to the disk below and moves with it, and there are now four points marked on the cover cap: D (Deferentis), H, E (Equantis), A (Mundi). Two threads are attached to the points A and E. Finally the epicycle disks for setting the argument are attached to the deferent circle. The computed century arguments of Mercury are shown in Table 15.

To work the volvelle you first set the mean longitude with index M in the same way as for the Sun. Then index P is set to the longitude of the apogee. By noting the value on the peripher- al, anti-clockwise zodiacal scale of disk P for the position of index M you determine the mean centrum. You then set index Q to the same value on the inner end of the slanting line by the clockwise scale. This will be approximately on the opposite side of index M relative to index P. The epicycle top disk is set to the argument. The epicycle disks (with the upper set disk lock- ed) are moved with their centre under the thread from E stretched to the inner end of the slanting line from index M, and the epicycle disks are rotated such that the cross of the lower disk is aligned with the E thread. Finally the thread from A is stretched through the star symbol on the top epicycle disk and the true longitude read off from the main zodiac scale of the mater.”

Lars: “The Ptolemaic model for the Moon (Figure 30) is slightly more involved than the model for the out- er planets and has some similarities with the model for Mercury. The centre of the deferent circle is attached to D that rotates clockwise around a smaller circle with centre A. The epi- cycle moves anti-clockwise on the deferent circle. The Moon moves clockwise on the epicycle. B is the location of the Sun. The angle BAC is the elongation from the Sun, equal to the angle BAD. FCP is the mean argument and GCP the true argument. The true place of the Moon relative to the Sun is then the direction of AP. The basis of all the Moon volvelles are three tables with the mean longitudes, arguments, and the positions of the node (Caput Draco) (Table 17).

This volvelle (Figure 31) has six disks stacked on the mater. The first disk, M, is centred on the mater and has an index tab marked M and with a Sun symbol. It is used for setting the longitude of the Sun. The periphery is divided into 100 equally spaced parts anti-clockwise. Inside this there is a scale with a year of 365 days and a scale graduated symmetrically clockwise and anti-clockwise from 0 to 250, starting from M. This is used to read the elongation and then set the double elongation, as will be described be- low. On top of disk M there is a disk P, also centred on the main axis. It has an index tab marked P and the text INDEX ME·MO·☽ and is used for setting the mean longitude of the Moon.”

1) Move the two layers of #14 on top of #21B. Then this volvelle would be correct sitting on the corect mater and in the right place. This is the volvelle for conjunction and opposition hours. > Deze heeft inderdaad 2 lagen, die dus op 21B zouden horen. In de plaats komen dan ALLE lagen van nummer 2 hierop, zodat deze weer klopt en eruit zou moeten zien als 14A hierboven toont.

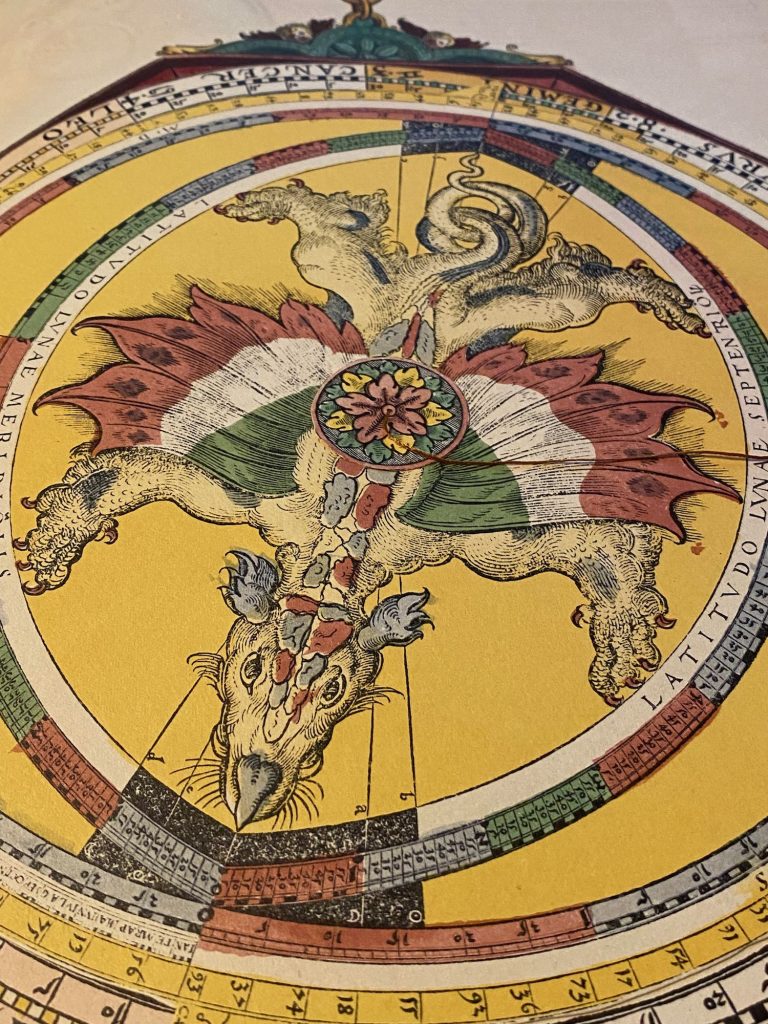

Lars: “A circular disk (Figure 34) is mounted centrally on the mater that has a zodiac scale. The disk has two tabs, one for the ascending node(d agon’ head, CAPVT) and one for the de cending node (d agon’ ail, CAVDA). There is a sequence of year marks and a smaller scale for setting the month and day. The year marks are calculated in the usual way but using the daily motion of the node (Caput Draco). In the centre of the disk is a picture of a dragon. Once the position of the node has been set on the scale of the mater, the latitude can either be read off by using the thread to mark the longi- tude of Moon on the zodiac of the mater or by marking the argument of latitude, the difference be ween he Moon’ longi de and he longi de of the node, on the scale on the periphery of the top disk. The latitude is read off from one of the arched scales surrounding the dragon. Effectively the volvelle computes the latitude of the Moon as 5°· sin(argument of latitude).”

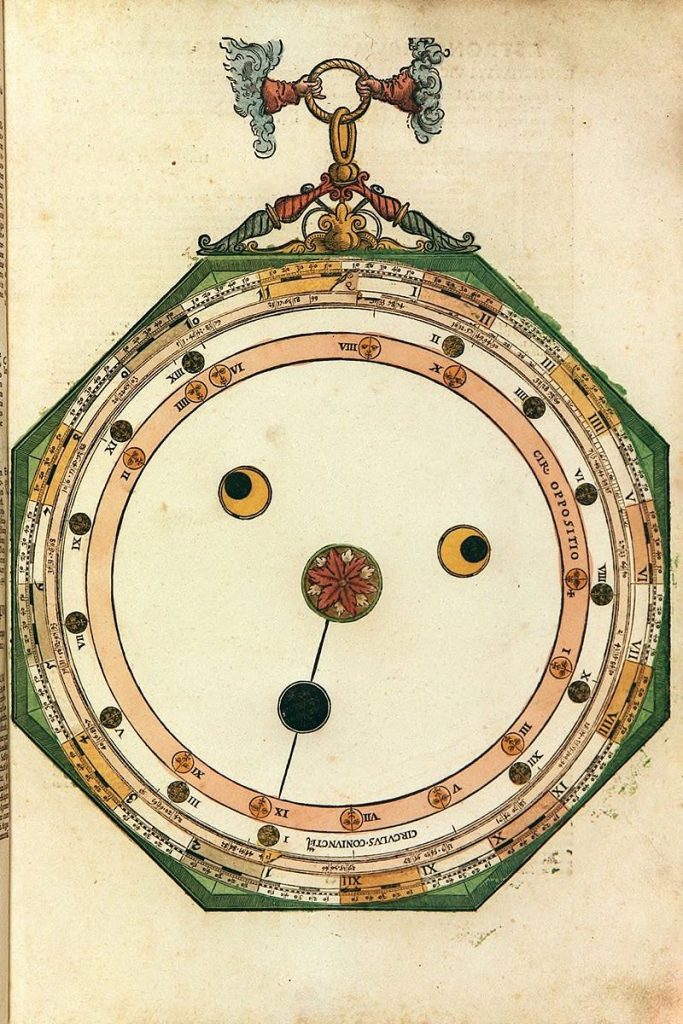

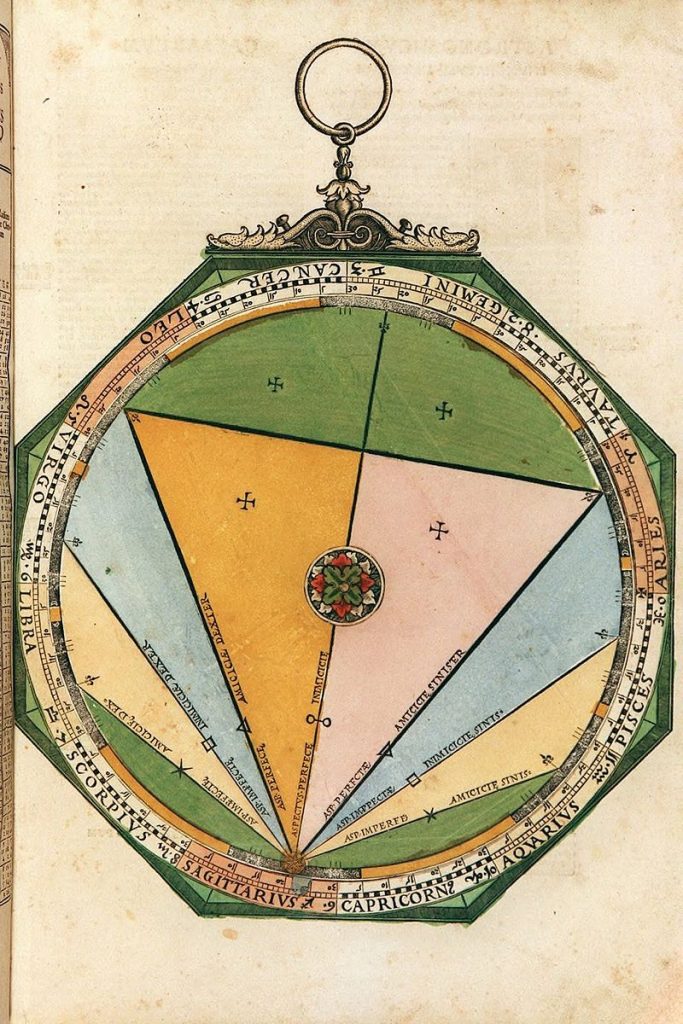

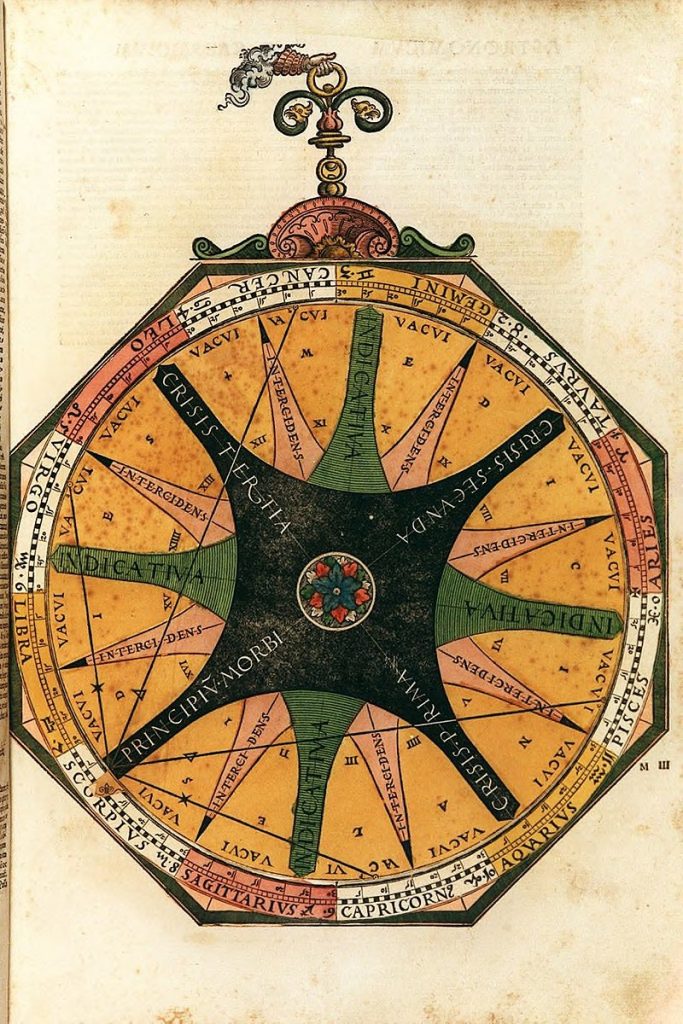

Lars: “The volvelle (Figure 36) on page 54 computes the aspects, or difference in longitude, between two astronomical bodies. The five aspects are: conjunction (0°), sextile (60°), quartus (90°), trine (120°) and opposition (180°). The different plan- ets can be within different angular sectors around the exact aspect: Mercury and Venus ±7°, Mars ±8°, Saturn and Jupiter ±9° and the Moon ±12°, while the Sun ±15° as is symm- etrically marked for each of the aspects marked on the volvelle. There is a moveable disk on top of the mater with an index X that can be set for the longitude of one planet and the thread from the centre that can be set for the longitude of another planet or the Moon or the Sun. The volvelles in pages 56 and 58 of AC (see Figures 37 and 38) are used to compute the time to reach an aspect between the Moon and a planet or between two planets, simply comput- ed as the ratio between the difference in longi- tude and the difference in angular speed. A thread with a small sliding bead is attached cen- trally. The difference, irrespective of sign, in daily motion is set radially with the bead and the difference in longitude, irrespective of sign, is set azimuthally with the thread, and the time is read off from the position of the bead.”

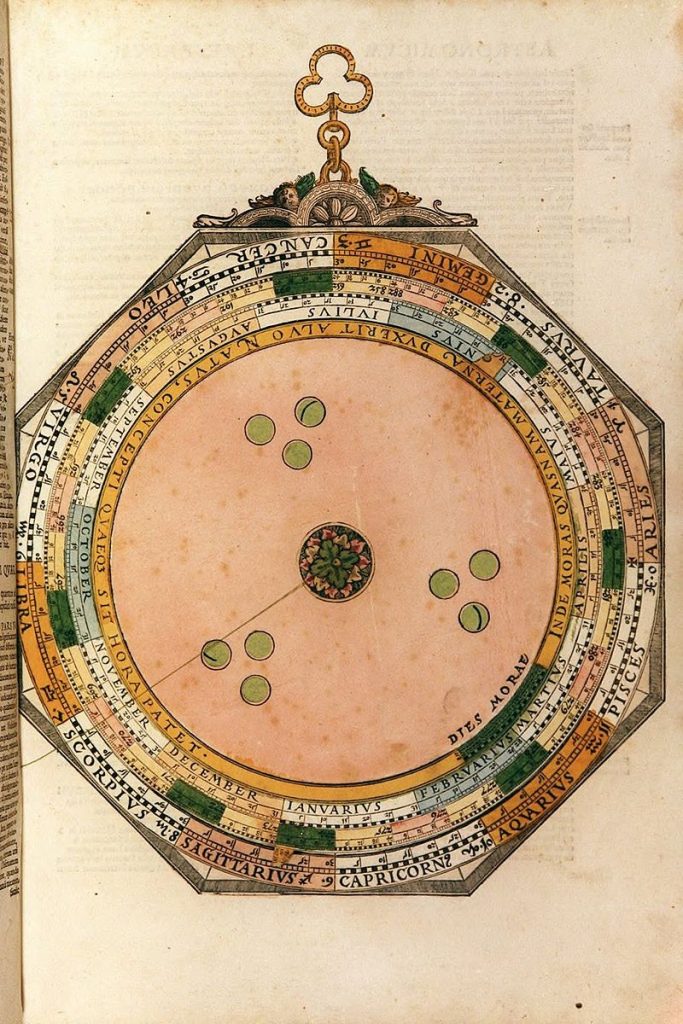

Lars: “This volvelle (Figure 39) is intended to be used in sequence with the following five volvelles to calculate the time and circumstances of eclipses. The table on page 59 of AC gives the day and time for each century in January for conjunctions of the Moon and the Sun and the Moon and its node. The unit in the table is days: hours: min- utes in January, the first occurrence of a con- junction in that month. The numbers in the table are calculated in the following way. First the number of months in a century is calculated by dividing the number of Julian days in the cen- turies (century number · 36525) with the lunar month length, synodic for the conjunctions with the Sun and draconic for the conjunctions with the node. This will result in an integer number of lunar months and a fraction. Multiplying one minus the fraction with the number of days in the lunar month and adding the radix (24:10:24 days for the synodic month and 23:6:33 days for a draconic month) will give the days remaining until the first conjunction in the century, i.e. the date of the conjunction in January. Whenever the date is larger than 31, a synodic or draconic month is subtracted in order to have the con- junction occur in January. This will generate Table 21. For the draconic dates there is a syst- ematic error of up to +5 minutes at the end of pian ’ able for centuries before Christ. The volvelle on page 61 computes phases of the Moon and also approximate eclipse dates. The mater has a circular scale with a 365-day year. The bottom moveable disk is mounted centrally on the mater and has a tab marked X and a set of year marks. The excess in days of ‘y’ years over 12 synodic months is aS = y ·(365 – 12·m) + integer((y –1)/4) + 1, m = days in a synodic month. This excess is normalised to be within one syn- odic month by setting ES = aS – m·integer (aS / m) Finally, in order to group the angles in ten-year portions a = (ES + m ·integer (y / 10))·360/365, where the last factors convert the days to de- grees. This will move the group exactly an integer number of lunations backwards in the year and avoids having the year marks on top of each other. The result is shown in Table 22. It is com- pared with the actual marks on the volvelle disk in Figure 40. There is a gap g between the index tab X and the start of the year numbers that is g = 365 – 11 · m = 40.163 days or 39.61°. A lunar year of 12 lunations is 12·29.530591 = 354.367 days that is 365 – 354.367 = 10.633 days shorter than a normal year of 365 days. Thus, if we start with lunation 1 on 1 January, lunation 12 will fall 10.633 days before the start of the next year. The previous lunation will then be 10.633 + 29.530 = 40.163 days before the end of that year. The intention of the gap is to keep Roman numbered new and full moons on disk Y (see below) within the year. On top of the previous disk is a second cen- trally aligned disk. It has an index tab Z and is used to set the excess days in years over 13 draconic months, 13·d = 353.76 days. The calculation is done almost as for the synodic ex- cess but using the days in a draconic month and using 13 draconic months. Finally, there is a top disk with dragon heads and tails and with a tab V. The positions of the heads and tails are generated by the same form- ula as above but instead using the days in a draconic month: an = n·d·360/365 n = 0 1 2 …,13 for heads 1, 2, 3,…,14 and with half integer n:s for the tails. Each head and tail is marked by its respective number. There is a dragon’s tail marked with a cross, that is the tail coming before head 1, for n = –0.5. Figures 43a and 43b show a compari- son with computer-generated radial lines com- pared with the heads and tails of the dragons. To use the volvelle, the X index is set to the radix days of the century in January taken from the table for the conjunctions with the Sun. Then the Z index is set to the century days in January of the conjunction with the node. This volvelle does not use elapsed centuries but current cen- turies. Disks X and Y are then locked in their set positions relative to one another. The Y disk tab is set close to the middle of January. The thread is lined up with the year of the century on the X disk and the Y disk is rotated such that the nearest New Moon on the Y disk is aligned with the thread. The dates of the different lunar phases can now be read from the symbols on the Y disk. In the same way, the V disk tab is set close to the middle of January. Note the dragon’s head that is closest to the year mark on the Z disk and use the thread to rotate the V disk such that this head is aligned with the year mark of the Z disk. The days of the passages of the nodes can then be read off from the top disk. Where the number of the head or tail of a dragon is close to the number of a New or Full Moon, you expect an eclipse of the Sun or the Moon and you will get an approximate date for the event. The numbers of the chosen conjunctions can be remembered and then used with the following volvelles to compute the mean time of a New or Full Moon or an eclipse. The lunar phases marked with crosses may fall in the pre- vious or subsequent year.”

Lars: “This volvelle (Figure 44) has a rather complex layout. It allows you to compute more precise eclipse times. It is a kind of zoomed-up version of the previous volvelle. It uses data from the previous volvelle where the date of a possible eclipse has been found. If it is an opposition (Full Moon) and occurs in the night, it may be a lunar eclipse, but if it is a conjunction (New Moon) and occurs in the day, it may be a solar eclipse. The mater has a circular graduation of 31 days for a full turn, each day being sub- divided into hours. The days spiral inwards and anti-clockwise to 31 December. As July and August both have 31 days, the same set of 31 days can be used. On top of the mater is a disk centred on the mater with an index tab marked XY. It has a set of year marks. Let y be the year. Then deter- mine an integer n such that (n – 1) · m < y · 365 + integer((y – 1) / 4) +1 < n ·m andcalculatetheanglea=((n·m–y·365+ integer((y – 1) / 4) + 1)·360 / 31. The last factors convert from the 31-day graduation to degrees…………”

This (Figure 49) is a further zoom-up of the previous volvelle. The volvelle has a mater divided into 12 hours, subdivided into minutes. It

has two disks, one on top of the other. The bottom disk has an index tab Q and a set of year marks. The marks are calculated by first determining an integer for each year such that (n – 1) m < y 365 + integer ((y – 1) / 4) < n · m, then set the angle a = 360 · frac (n · m – y · 365 integer((y – 1) / 4)). frac(x) is the fractional part of a number, for instance frac(10.578) = 0.578. This procedure generated Table 28 and Figure 50. The top disk has an index tab P. It has two bands with Moon icons, the outer band with New Moons and the inner one with Full Moons. The New Moons have Roman numbers I – XIII, the Full Moons I – XI, and one Full Moon is marked by a cross. Angles for the respective Moons are generated by: New Moons 360 · frac((n – 1) · m) n = 1 2 … 13 Full Moons 360 · frac((n – 0.5) ·m), n = 1, 2,..,11

Crossed Full Moon 360 · frac(– 1.5) m = – 106.52° = 253.48° We get Table 29 and Figure 51. New Moon IIII is slightly misplaced and Full Moon VI much so. First tab P is set to the value of the hours for the century from the century table concerning conjunctions with the Sun. Then tab Q is set on the year within the century. You can now read off the times of the day for the sequence of New and Full Moons of the year.

1) Move the two layers of #14 on top of #21B. (and hides the sunrise/sunset centre). Then this volvelle would be correct sitting on the corect mater and in the right place. This is the volvelle for conjunction and opposition hours. (It produces the volvelle for conjunction, opposition and eclipse times. It will have the correct circumference in the mater.)

2) Move all the layers on top of #2 to the now free mater #14. Except for the mater, this volvelle will now be in the correct place. This is the volvelle for the Moon’s longitude.

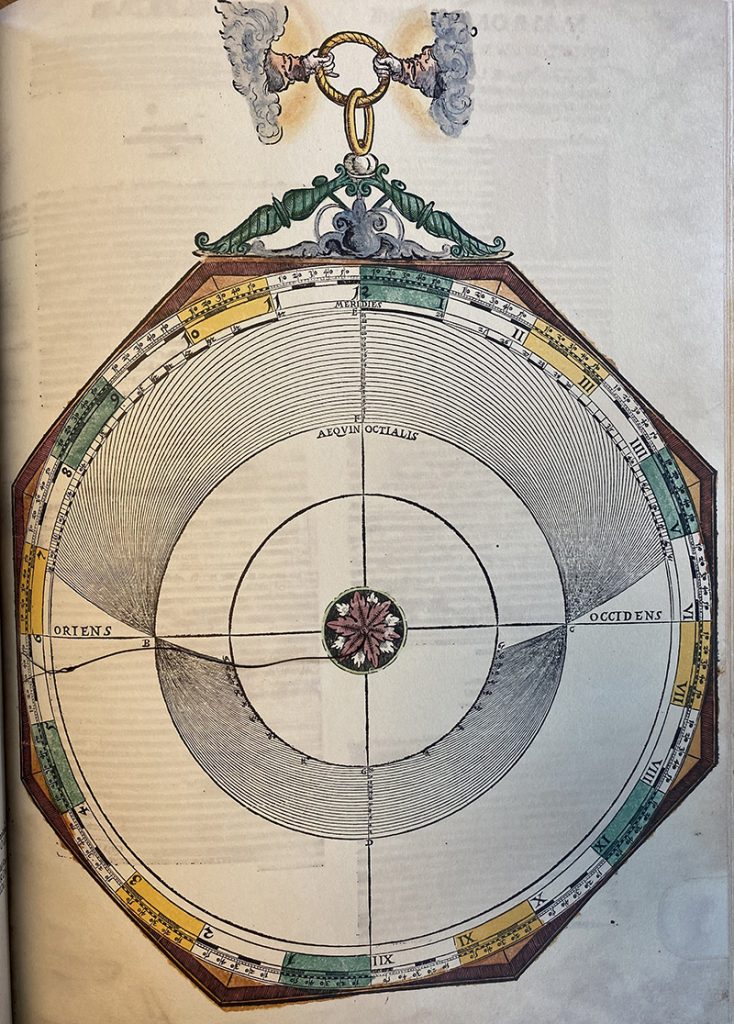

Deze stond niet beschreven in de documentatie van Lars, maar toen ik hem erover mailde, kreeg ik aanvankelijk het antwoord dat hij deze niet kende (andere editie gebruikt als basis?) Een paar uur later had hij de noot gekraakt en kreeg ik weer een mail, met zijn uitleg en een screendump van de resultaten van zijn Java applet. Daar hou ik van ! Dank Lars. Ook voor de 2e / verfijnde poging die hij met een Adobe script had gemaakt.

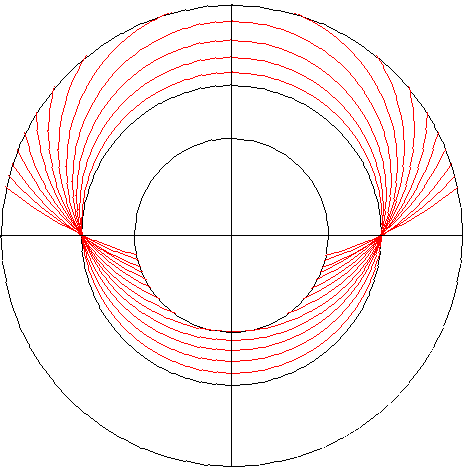

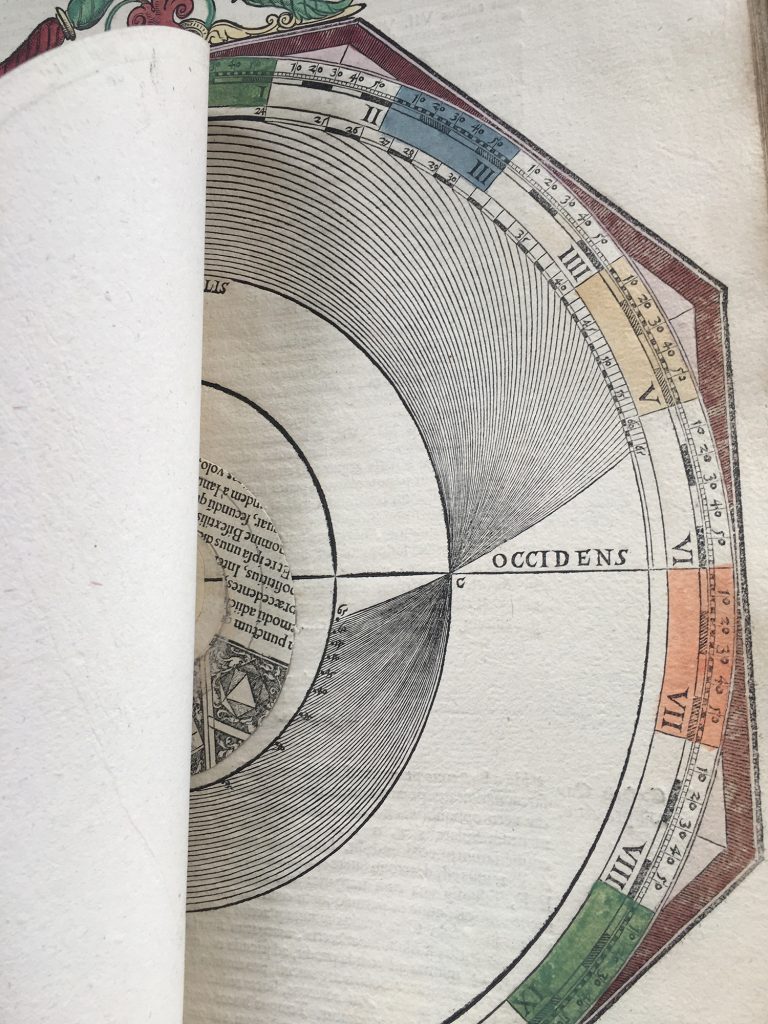

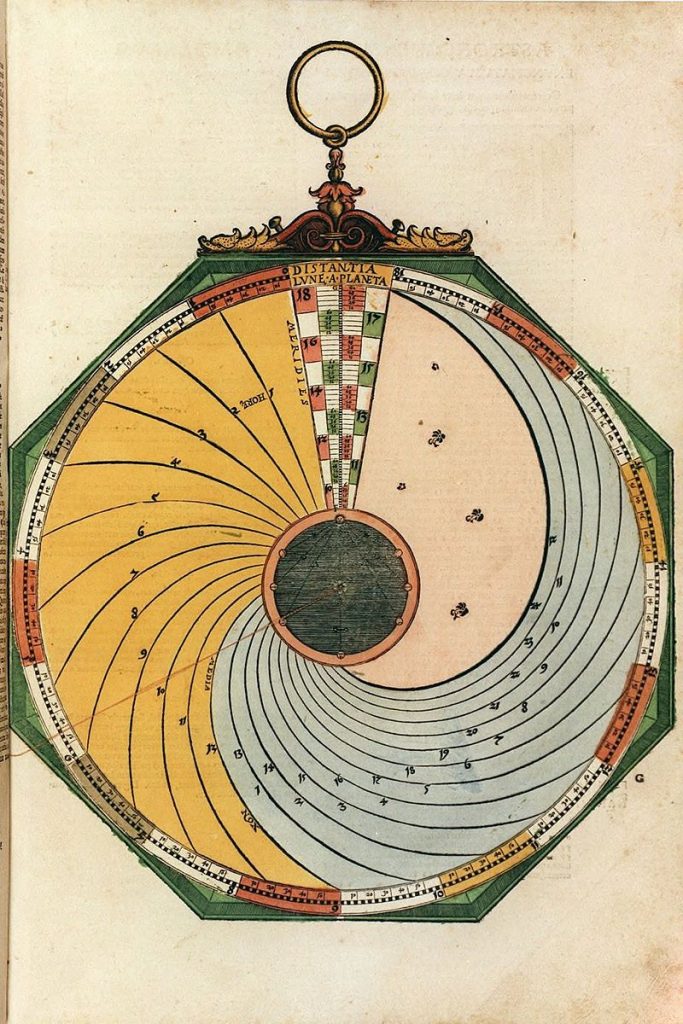

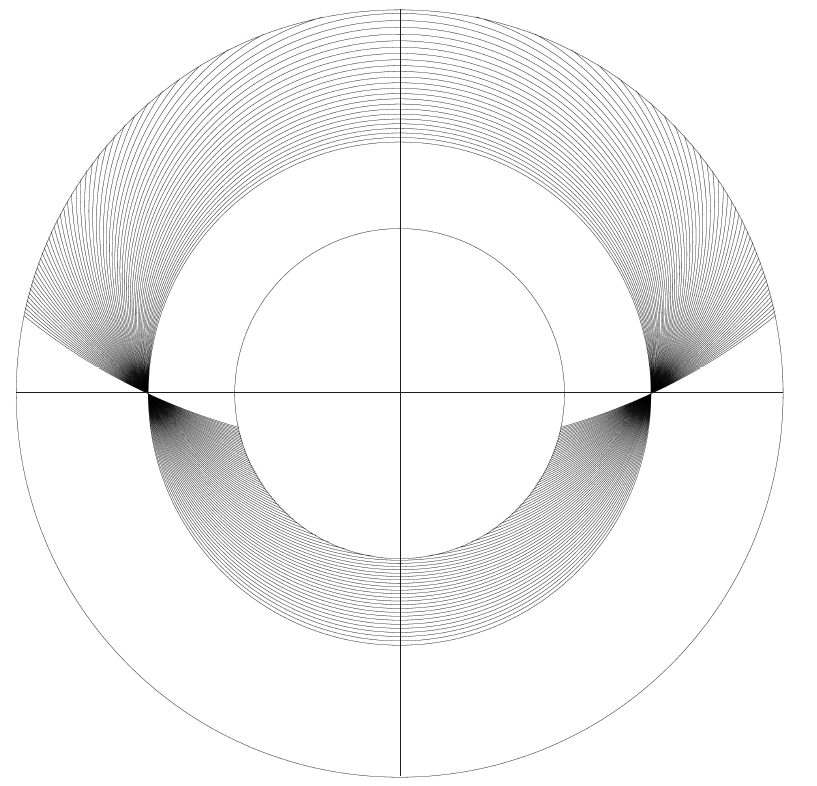

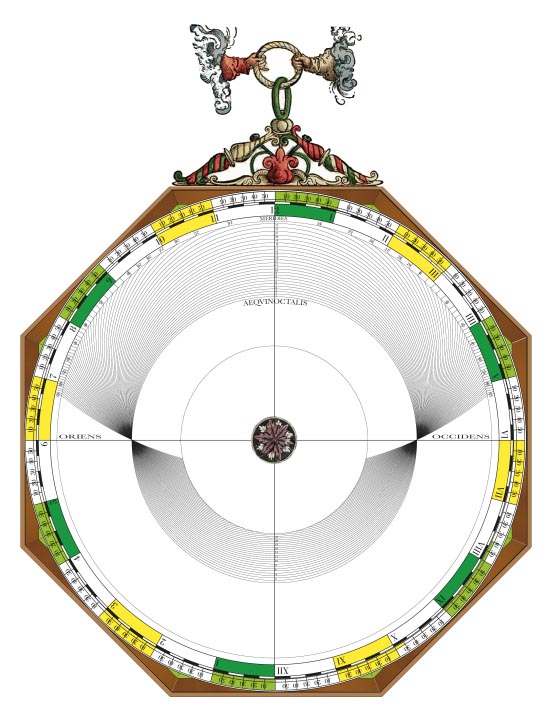

Hi Bas, I solved the volvelle. It is used to find sunrise and sunset times. I wrote a small Java program that simulates it, see attached picture. It is a stereographic projection.The inner circle corresponds to the Sun having declination +24˚, the middle circle 0˚, the largest circle -24˚ a so called south stereographic projection. The red curves are projections co-latitudes (90- latitude) horizonts, 0–65˚ with intervals 5˚

The way you use it is:

1) Set the pearl on the thread to the solar declination using the red curves where they cut the vertical symmetry line. Negative declinations at the top, positive ones at the bottom.

2) Rotate and stretch the thread such that the pearl is just above the curved line connected with the co-latitude.

3) Read off the time of sunrise or sunset on the peripheral scale.

You can also use the volvelle to find the co-latitude if you know the time of sunrise or sunset.If you know the time of sunrise or sunset and the co-latitide you can find the Sun’s declination.

As usual a clever Peter Apian instrument! Best regards, Lars

Alles wat je hieronder dus ziet is van voor we uitvoerden wat er allemaal niet klopt aan de Volvelle. Vroeger kon je van de uitgever een handleiding krijgen hoe de Facsimile weer correct te maken: Dan moet je aan de gang met schaar, touw en lijm aan de slag: doe ik mnog even niet.

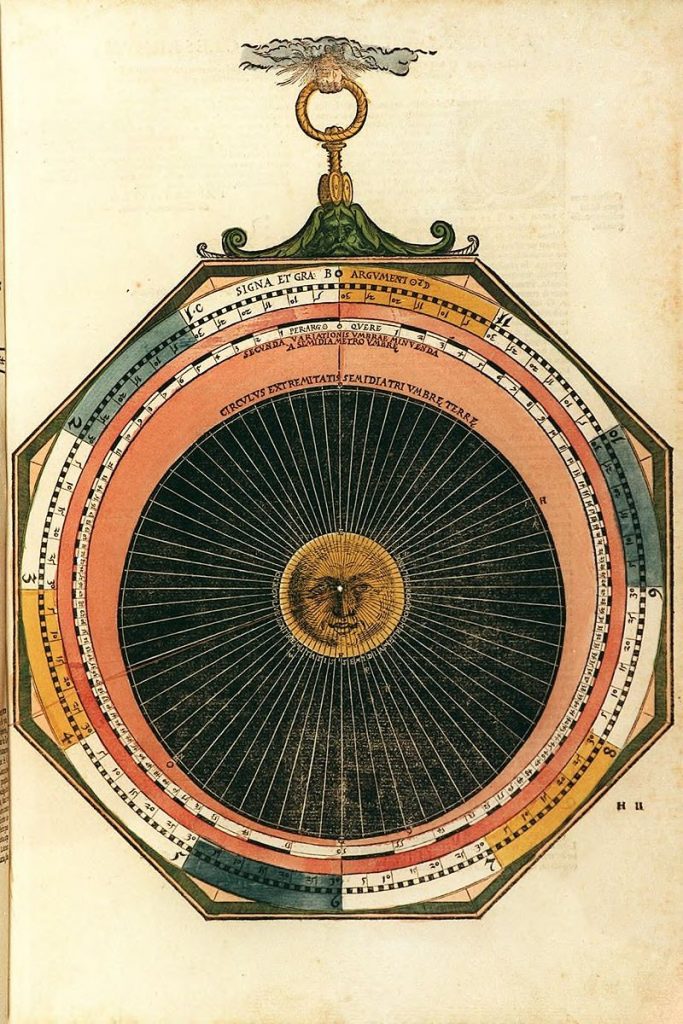

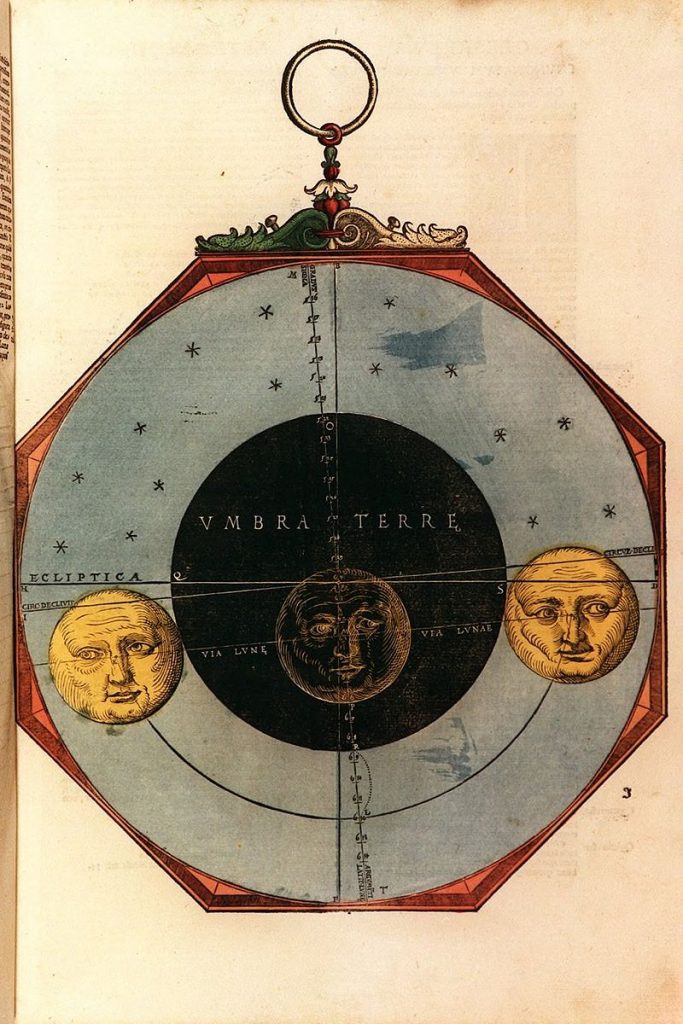

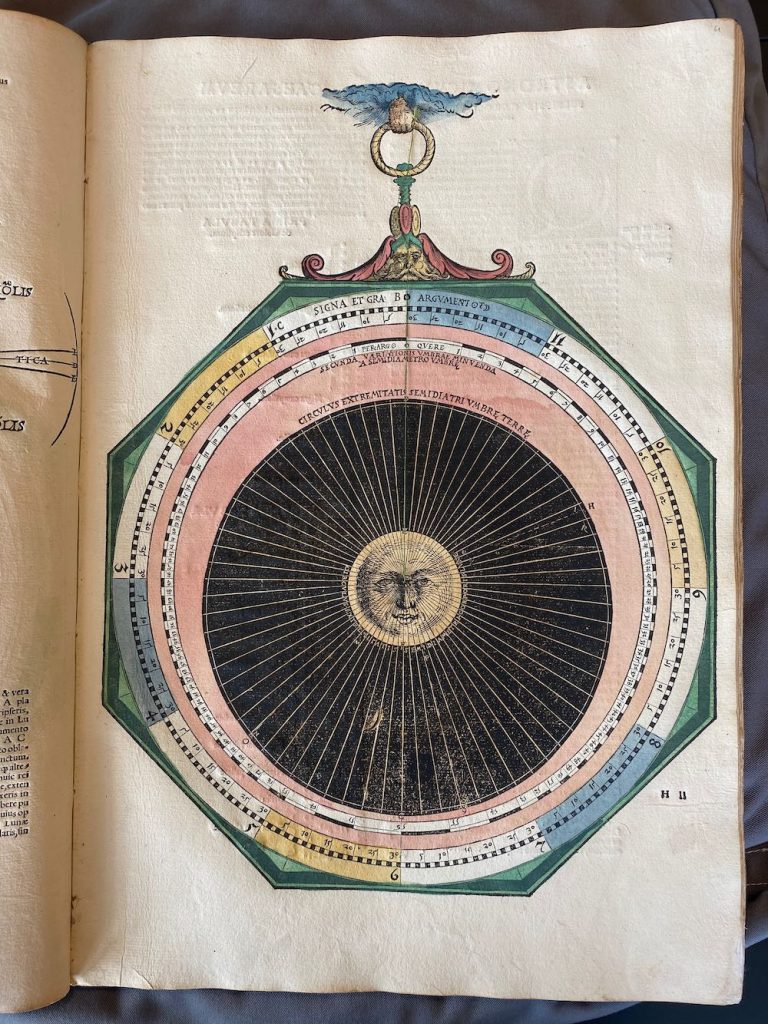

Lars: “The mater of the volvelle (Figure 53) is gradu- ated along the rim with a scale with the zodiacal signs 0 – 11, subdivided into degrees. It is used to set the Moon’s argument, which essentially measures the distance to the Moon, or to set the argument of the Sun. Inside this scale is a scale offset from the centre and graduated symmetric- ally from the top clockwise and anti-clockwise from 0 to 56. Finally, there is a large black circular area representing the Ea h’ hadow and a yellow central circular area representing the Moon and finally a thread attached to the centre of the volvelle. Both these areas are displaced from the main centre of the volvelle. The ratio of the radii of the two areas is 2.6, a Ptolemaic value for lunar eclipse. In the Alfonsine Tables, the angular size of the of radius of the shadow is a function of the lunar argument and varies between 46′ 47′′ and 37′ 41′′. The ratio of these angles, 1.24, is also very precisely the ratio between the largest and smallest distances from the centre to the periphery of the shadow area and of the largest and smallest distances from the centre to the periphery of the Moon area. The Ptolemaic theory also assumes that be- cause of the varying distance to the Sun, the radius of the shadow has a correction, depending on the argument of the Sun, that is propor- tional to the square of the sine of the solar argument, and with a maximum value of 56′′. This is the purpose of the offset scale inside the outer scale on the mater. The working of the volvelle is double. Using the central thread to set the argument of the Moon, the radii of the shadow and the Moon can be read off. Then, using the thread to set the solar argument, the small correction to the shadow radius can be read off from the scale graduated from 0 to 56. These quantities can then be used for the graphical construction of lunar eclipses that is illustrated by the volvelles on pages 70, 72 and 74.”

Lars: “This is one of the odder volvelles (see Figure 56). The ascendant or rising sign at the hour of birth was used for the construction of horo- scopes, which at the time was one of the important tasks of some astronomers. The prin- ciple of the volvelle is the belief that the ascend- ant at the conception is the same as the longi- tude of the Moon at birth, and that the longitude of the Moon at the conception is the same as ascendant at birth. Even if you only know the ascendant approximately at birth, this volvelle is said to compute the true time of conception, and the longitude of the Moon can then be comput- ed, leading to an improved value for the ascend- ant at birth. The mater has a scale with the zodiac. On top of this, and attached to the main axis, is a disk with the circumference divided into 30 parts labelled 258 to 288, each part subdivided into 24 hours. Inside this is a scale with the days of the year. The disk has a tab Q and is also marked by ASCENDENS. On top of this is a circular disk, also moving around the main axis with a tab R and a small sector scale DIES MORI with 30 divisions labelled 258 to 288. The width of the sector precisely corresponds to 30 days on the year scale of disk Q. The thread from the centre is set to the longitude of the Moon at birth on the scale of the mater. The tab Q of the ascendant disk at birth is set to the longitude of the ascendant at birth on the same scale. By the thread you can now read off how many days and hours the child has been in the womb of the mother. Further, set the thread to the date and hour of birth and then move the tab R of the top disk such that the number of days and hours in the DIES MORE scale is against thread, and you can read off the date and hour of the con- ception at tab R. The top disk merely performs a subtraction of the days and hours found above from the time of birth. The time of conception can then be used to compute the longitude of the Moon at that time and by that the ascendant at birth.”

Lars: “This is also an astrological volvelle (Figure 57). Pars Fortunæ is computed by two formulas: for day horoscopes it is the longitudes of the ascendant + the Moon – the Sun, while by night the roles of the Moon and the Sun are switched and the volvelle performs these mathematical operations. Pars Fortunæ is said to represent worldly success and to be associated with health as well in some rather unclear way. There is a mater with a zodiac scale. There are two disks on top of one other and centred on the main axis. Three input numbers are requir- ed: the ascendant, and the longitudes of the Moon and of the Sun. If the birth is by night, the bottom disk is set to the longitude of the Moon and the top disk to the longitude of the Sun. Both disks are then moved together until the tab of the bottom disk points to the ascendant longi- tude on the mater. Tab T will then point to the Pars Fortunæ or longitude of luck. If the birth is by day, the bottom disk is instead set to the solar longitude and the top disk to the lunar one.

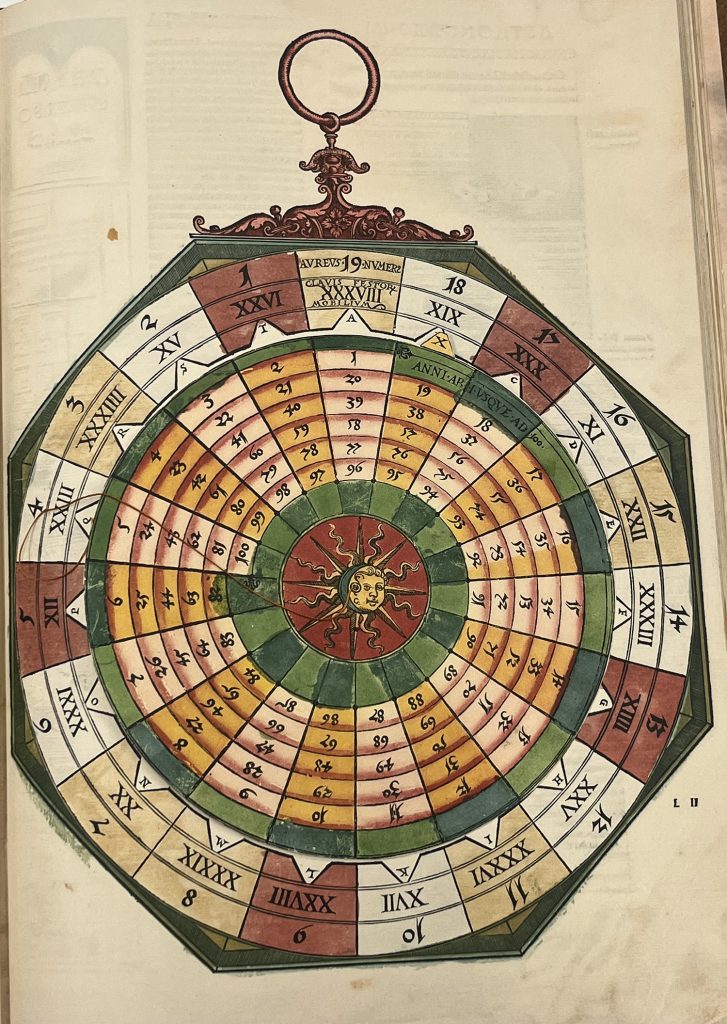

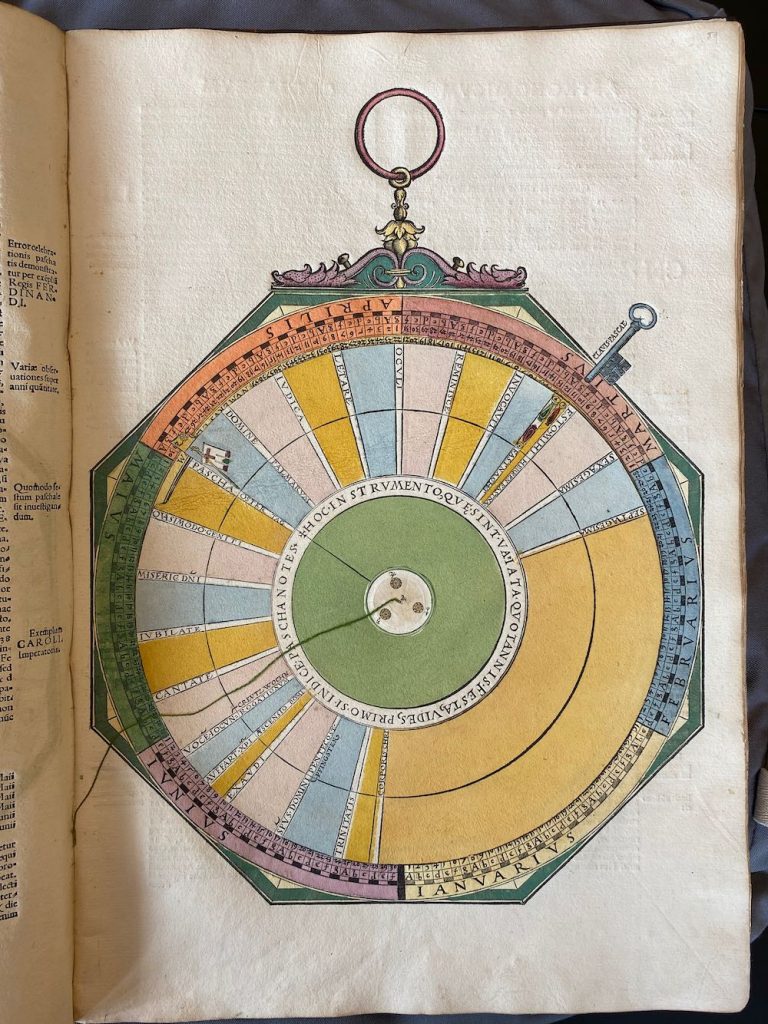

Lars: “This volvelle (Figure 58) does the computation of the golden number (AUREUS NUMER) or the year in a 19-year cycle using a century letter value taken from the table on the previous page, set on by a tab X on the top disk of the volvelle and reading off the golden number using the central thread and the year within the century. The volvelle then also shows the key for the moving ecclesial feats, CLAVIS FESTOR MO- BILIUM. The implemented formula is that the goldennumberG=(year/19)mod19+1. For instance, 1,500 CE gives a remainder of 18 and a golden number of 19. This volvelle uses cur- rent years, not elapsed years. The key for the moveable seasons is used in the volvelle on page 96 to determine the Easter Sunday that then in turn determines the moveable ecclesial feasts. In the Julian calen- dar, Easter Sunday is the first Sunday after the first ecclesial Full Moon, the Easter Full Moon on or after the ecclesial equinox, 21 March. The Easter Full Moon is calculated by cyclical reck- oning, and is in general different from the astro- nomical Full Moon. In fact, in the Julian Calen- dar the Easter Full Moon drifts away from the true Moon by more than three days per millen- nium. The Easter Full Moon is determined by first computing the epact E = (11 · (G – 1)) mod 30. In the Julian Calendar the epact is the age of the Moon on 22 March. The Easter Full Moon occurs when the epact is 14 and Easter Sunday can occur the day after, at the earliest. If the epact is equal or less than 15 the Easter Full Moon can then occur 15 – E days after the equi- nox; if it is more than 15, it occurs 30 days later, i.e. after 45– E days. The key counts these days from 11 March, starting the count on that date, thus if the epact is equal or less than 15, the key will be 26 – E, otherwise 56 – E. This will give Table 30 with the relation between the golden number, G, the epact and the key number, which are the numbers (except for the epact) that you find on the volvelle. It also shows the date of the Easter Full Moon (EFM) that is uniquely de- termined by the golden number.”

Lars: “This volvelle is shown in Figure 59. The domin- ical letter determines the Sundays of the calendar. The Julian Calendar with a leap year every four years, combined with the seven-day week, generates a cycle of 4·7 = 28 years after which the weekdays of the year will fall on the same dates. Each day of the calendar year is labelled sequentially with the seven letters A to G, starting with A on 1 January.”

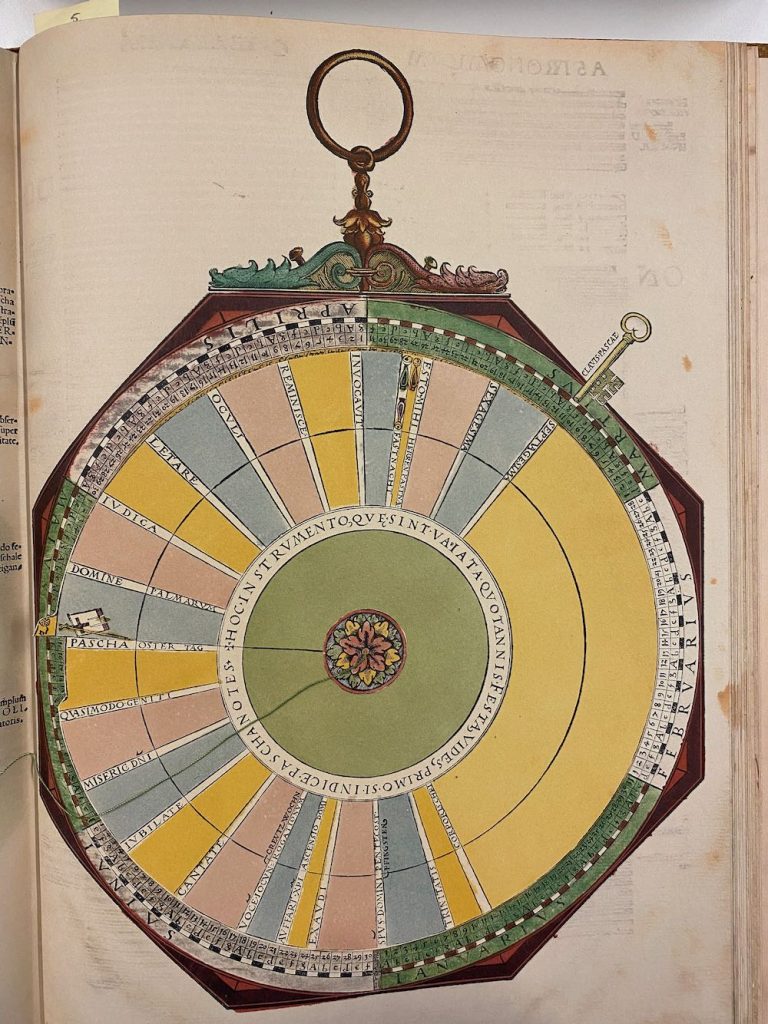

Lars: “This volvelle (Figure 60) has a mater with the months and days of the year and the sequence of dominical letters and a moveable upper disk with a tab for Easter Sunday, PASCHA OSTER TAG. There is a key icon labelled CLAVIS PASCAE pointing to 11 March. The ecclesial equinox was on 21 March. However, because the Julian mean year of 365.25 days is longer than the true tropical year of 365.2422 days, the true equinox would slowly recede in the calen- dar and at Apianus’ time the true equinox occur- ed approximately on 11 March, which is probab- ly the reason why he put the Easter key at that date. The recession of the equinox would event- ually lead to the Gregorian Calendar reform in CE 1582. Using the key value from the volvelle on page 92 and the dominical letter from the vol- velle on page 94, you count off the key, starting with one on 11 March to reach the date of the Easter Full Moon. You then search the first date with the given dominical letter after this date and this will be Easter Sunday of the year. Here is an example: 1540 CE has the key 15 and as it is a leap year it has two dominical letters D and C. As we deal with a date after 29 February, the dominical letter to use is C. Counting off the key starting from 11 March you reach 25 March. The first dominical C after that date is found on 28 March, which will be the date of Easter Sunday. Setting the tab on this date you can now read off the dates of the other ecclesial feasts. In the Julian Calendar there are precisely 19 dates on which the ecclesial Easter Full Moon can occur. Combining this number with the solar cycle of 28 years after which the weekdays fall on the same date, we get the Easter cycle of 28 · 19 = 532 years after which Easter Sunday falls on the same date in the calendar.”

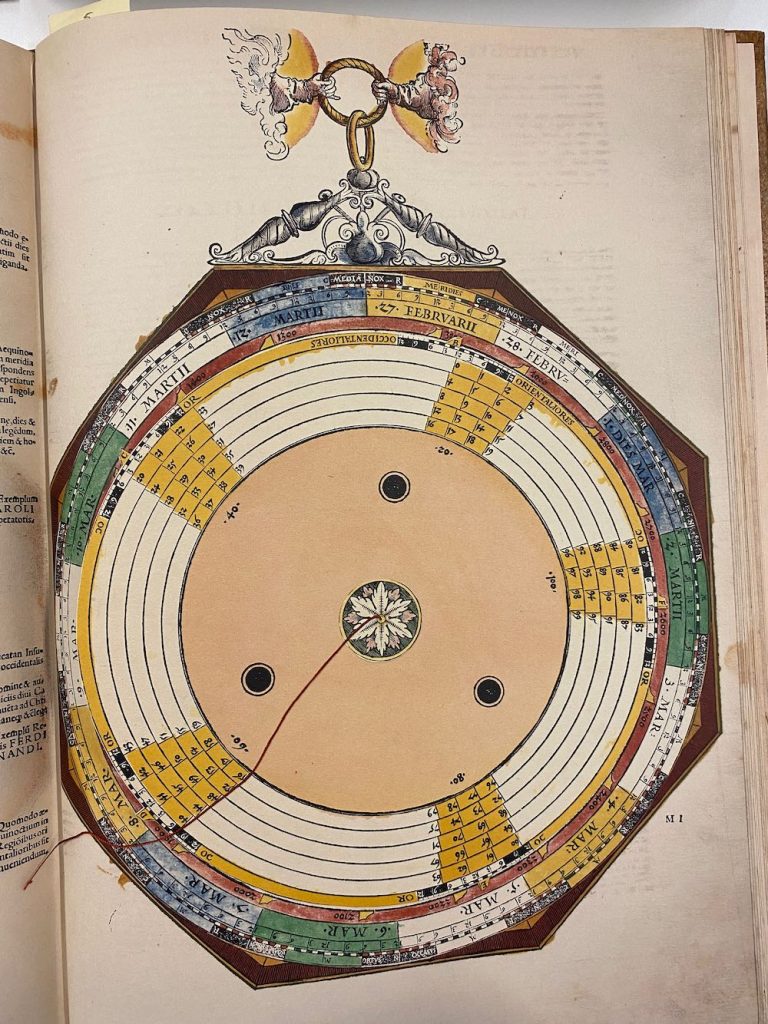

Lars: “The equinox volvelle (Figure 61) consists of the mater and a moveable top disk that can be rotated around the central axis. The mater is graduated by the fourteen days on which the equinox can fall in the selected time interval 1,300 CE–3,000 CE. Thus, a day corresponds to an angle 360 / 14 = 25.714°. Each day is sub-graduated by 24 hours from 12 hours mid- night to noon to 12 hours midnight. Night and day portions are indicated by an outer circular band with white and black partitions. In the middle of the night part are the words MEDIA NOX or just NOX, in the middle of the day part the words DIES or MERI(DIES) or just M. In the innermost circular band of the volvelle are eight- een fixed indexes marked 1300 to 3000 for cen- turies after Christ. The index for century 1500 is marked with M. When the specified year is a leap year the February dates on the top of the mater should be 28 and 29 instead of 27 and 28. The moveable top disk has five equally spaced tabs marked B, C, D, E, and F. Below each of the tabs is a group of twenty years of the century, grouped in five concentric circular bands, each having a sequence of four years.

In the circular band immediately below the tab there is a scale from 12 hours midnight over noon to 12 hours midnight. To the right of this scale are the letters OC (occident, west) and to the right OR (orient, east). This scale is used for geographical time difference corrections for lo- cations west or east of Ingoldstadt, the meridian used for AC. Finally, there is a thread from the centre of the volvelle to be used for reading off the time of the equinox. The instrument uses the Julian Calendar with a mean year length of 365.25 days. The tropical year used in AC is 365.2425461 days. A Julian century is 36,535 – 36,524.25461 = 0.74539 days longer than the tropical year. In the volvelle this corresponds to an angular in- terval of 0.74539 · 360/14 = 19.167°. Figure 62 shows a series of century radial lines with this angular separation, starting from the index 1300. The agreement with the volvelle is excellent. This angular condition only fixes the relative positions of the century indices. Apianus need- ed to calculate the absolute position of one of them. The one marked with M for 1,500 CE is the natural choice. In fact, if you calculate the true equinox for 1,500 CE, using the Alfonsine Tables, you get 10 March, 5:13 hours after noon. dding o hi pian ’ ab la ed longi- tude time difference with Toledo, 1:29 hours, you arrive at 10 March, 6:42 hours after noon, which is very nearly what you find on the volvelle (Figure 62, red line from index M). In a 20-year period there are 7,305 Julian Calendar days and 7,304.850922 tropical days. The difference is 0.149078 days or 3:35 hours. This difference is used in the top disk. Each group of 20 years is successively displaced pre- cisely this number of hours anti-clockwise rela- tive to index of the group as you go from index to index. In a 4-year period there are 1,461 calendar days and 1,460.970184 tropical solar days. The difference is 0.029816 days or 0:43 hours. The four-year groups within each 20- year group are displaced anti-clockwise relative to each other by this amount. The difference between a tropical year and a normal Julian year and is 365.2425462 – 365 = 0.2425462 days or 5:49 hours. In each four-year group, the years are successively displaced clockwise by this amount. All this accounts perfectly for the layout of the volvelle. The working of the volvelle is that the tab of the top disk with the 20-year group containing a specified year is placed on top of the index of the chosen century. The thread is aligned with the line representing the specified year in the 20-year group, and the time and day of the spring equinox are read out from the mater. If necessary, the time is corrected for east-west longitude time difference, using the time scale below the top disk tab. To find the corres- ponding autumn equinox you add six months, three days, and 42 minutes. Due to the difficulty in reading the time scale the result has an ef- fective precision of about 10 minutes. In the examples given by Apianus in AC, he states the time with a precision of minutes, but he has clearly obtained his result by some other means of computation. There is a more detailed explanation of the theory behind this volvelle in Gislén (2019).”

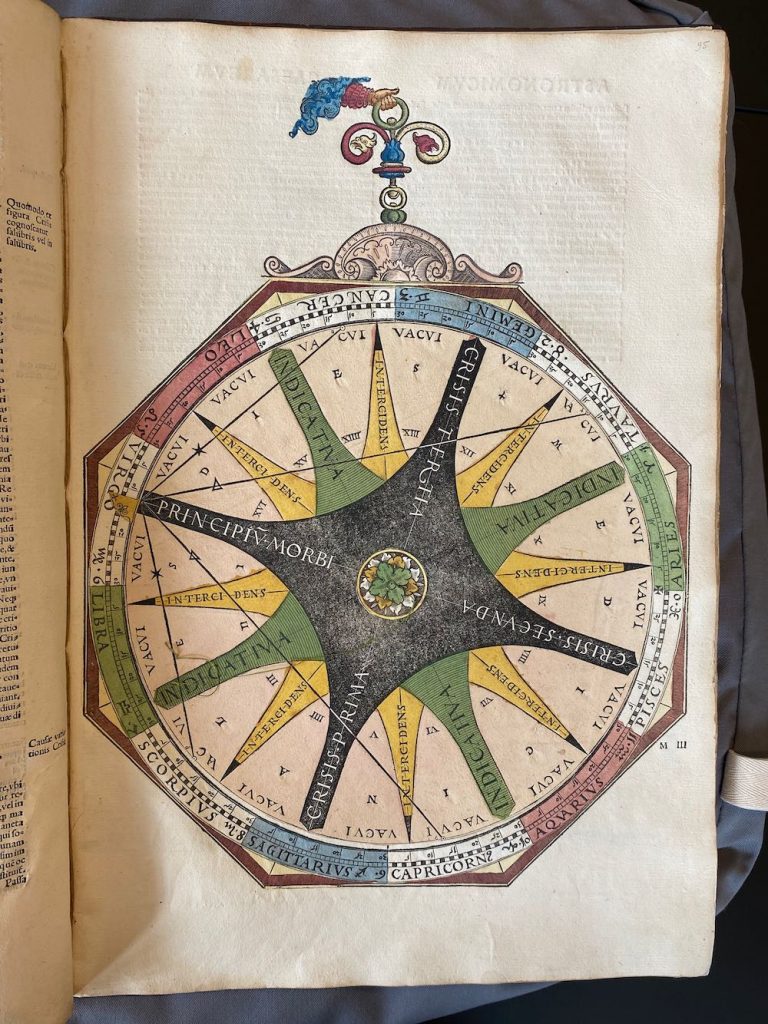

Lars: “The last volvelle (Figure 63) is purely astrolog- ical, deals with the connection between astrol- ogy and medicine, and uses the longitude of the Moon as input. I have not investigated the details of this volvelle.”

3 Volvelles corrigeren, dankzij Lars

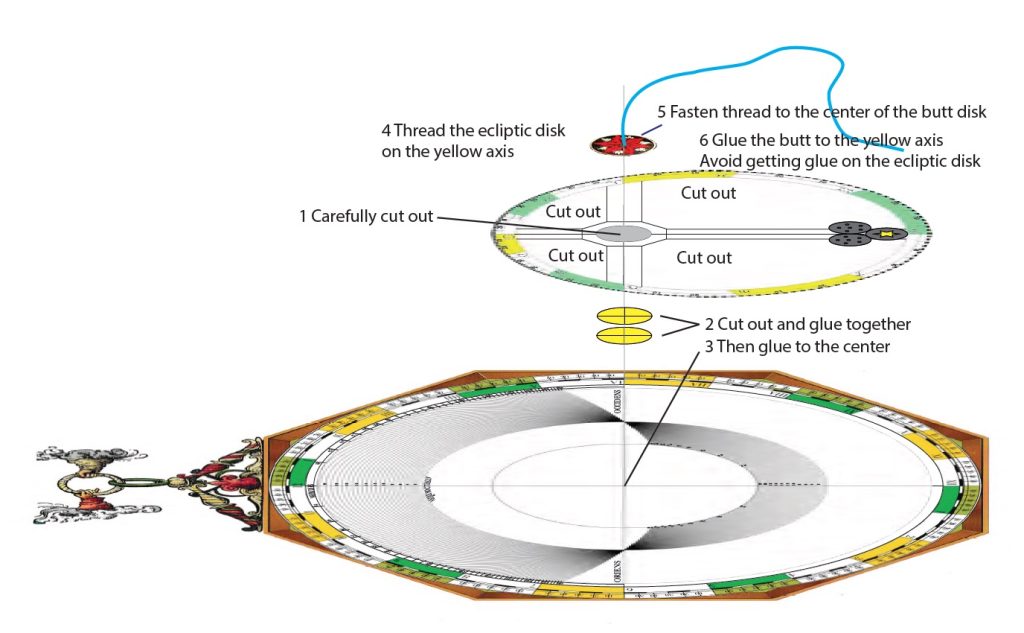

Het duurde even voor ik tijd had, maar vandaag heb ik alle materialen die Lars me stuurde kunnen bekijken en op ware grootte in Illustrator opgemaakt: 7 lagen precies op elkaar passen. Carlo hier in Schaijk kan printen op het formaat van het boek: 447×308 mm, nog groter dan A3. N nummer 1 is alleen de mater (1 laag), 14 heeft in illustrator wel 9 lagen met de ‘afwerkdopjes’ erbij en 21 heeft 4 lagen in totaal. Alles op 300 grams printen en dan alles uitsnijden voor de handleiding gevolgd kan worden. Jane had prima touwtjes en zo gaan we morgen aan de knutsel. Tijd genoeg want ‘Sometimes it snows in April’, zoals nu…

Jane had exact het goede touwtje. Wel met de hand op kleur gebracht. Hele middag mee bezig geweest. Met name nummer 14 is erg complex met meerdere assen (van touw en van karton) en maar liefst 7 lagen. Eén dingetje was ik vergeten te printen, maar Carlo was er nog en zo kon ik het mooi afmaken vanmiddag in de sneeuw. Niet alleen blij mee, maar ook trots op. Netjes gelukt en goed opletten, maar Lars had geweldige bestanden en instructies gestuurd. Nu is ook de facsimile versie mooi compleet, al is het dan door deze drie bijlagen.

Recreate Volvelle 14 yourself !

Good news: Lars agreed to have Volvelle14 available to all so you can try and recreate it yourself. It is on a larger than A3 size, but only by a little so scaling it back is not a problem. More professional printers will have the exact size it is created on, which is also the size of the original book. Please download the 40 MB file here!

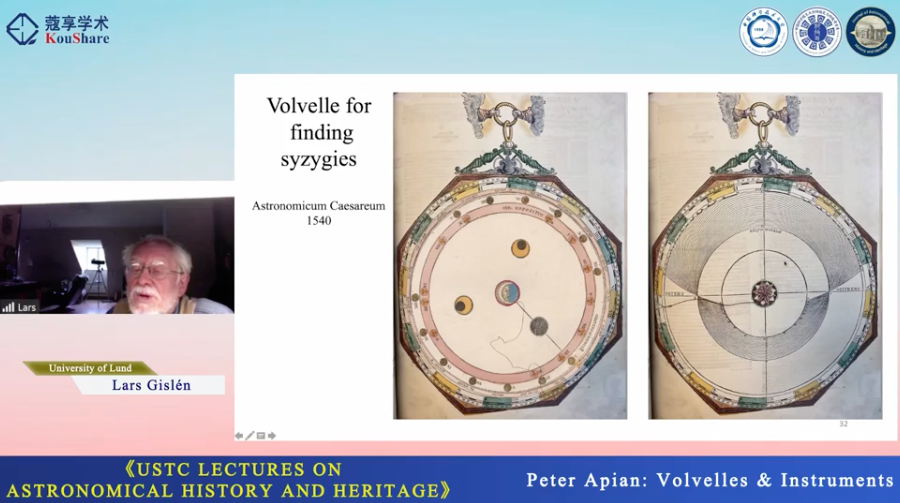

Lecture door lars – The Hidden Volvelle

Een lecture door de 85 jarige Lars Gislen voor USTC in China over de papieren rekenmachines van Apianus. Bij 1:02:30 praat hij over de verborgen volvelle, die recent is ontdekt (door mij/ons dan, ook al was het in 1969 ook al eens gevonden…) Bekijk zijn lecture hier.

Maak nu zelf de papieren rekenmachine die bij de mater van Volvelle 21 hoort

Update September 2024

Lars Gislen heeft het doel achterhaald voor de ongebruikte mater en heeft op basis van andere boeken en papieren rekenmachines van Apianus de ‘ontbrekende’ volvelle alsnog kunnen reproduceren. Ook heeft hij de tool uitgewerkt en samen hebben we er een printbare PDF van gemaakt, zodat je ook deze ‘rekenmachine’ zelf kunt namaken. (Tip: laat op A3 afdrukken op 300 frames papier)

Wat eraan vooraf ging

– Ik vond de verborgen mater in mijn (elke) facsimile van de originele Astronomicum Caesareum

– Lars Gislen dook erin en zocht uit wat er precies het verschil was tussen origineel en facsimile. Al snel had hij door wat het doel was van de lege mater: “It is used to find sunrise and sunset times. I wrote a small Java program that simulates it, see attached picture. It is a stereographic projection.The inner circle corresponds to the Sun having declination +24˚, the middle circle 0˚, the largest circle -24˚ a so called south stereographic projection. The red curves are projections co-latitudes (90- latitude) horizonts, 0–65˚ with intervals 5˚”

– Samen hebben we de 3 verkeerde volvelle’s gecorrigeerd en als downloadbare prinsbestanden beschikbaar gemaakt voor geïnteresseerden (Lars de theorie / techniek en ik de opmaak / printbaarheid)

– Lars is dagelijks bezig met onderzoek naar dit soort 500 jaar oude papieren rekenmachines en heeft aan de hand van eerdere boeken van Apianus, de ongebruikte mater toe kunnen kennen aan de tool waarvan hij denkt dat hij orgineel voor was bedoeld, maar dus nooit zo in het boek is opgenomen.

– Het patroon in de facsimile represented volgens Lars (en ik geloof hem direct): Longtitues in geographic position, for finding sunrise (for example)

– Hij heeft in feite een extra volvelle aan het boek toegevoegd door de ongebruikte mater alsnog compleet te maken met de kennis van de andere boeken. Deze nieuwe papier rekenmachine heeft hij uitgewerkt tot een printbaar bestand

– Naast de drie gecorrigeerde volvelles nu dus ook een extra volvelle die Apianus ons in 1540 heeft onthouden. (Volvelle 21 uit de facsimile)

– Het instrument komt wel voor in een eerder boek van Apianus uit 1524, ook daar zat het horizon patroon verstopt onder de andere schijven. Hier heeft Lars een paper over geschreven: The artful early instruments of Peter Apian: Ein kunstlich Instrument of 1524, its precursors and its successors, by Lars Gislén (University of Lund, Sweden) and James Evans (University of Puget Sound, USA) gepubliceerd in Journal for the History of Astronomy, May 2024. (Link to article)

– Je kunt ze nu alle vier zelf namaken: de 3 gecorrigeerde en deze nieuwe ontbrekende !

- Link naar download van de 3 gecorrigeerde Volvelles: https://www.dropbox.com/s/2h895um2owgztsu/LarsGislen_AC-Volvelle14_PrintSet2.pdf?dl=0

- Link naar download van deze extra ‘aanvankelijk verstopte’ volvelle: https://www.basgriffioen.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/TheHiddenVolvelle21.pdf

- Link naar een oude homepage van Lars over zijn werk: http://home.thep.lu.se/~larsg/Site/Welcome.html

- Link naar zijn meer up to date pagina bij de Lund Universiteit: https://portal.research.lu.se/en/persons/lars-gisl%C3%A9n

Overzicht alle 750 edities (een poging)

Owen Gingerich deed er 25 jaar over om 111 van de 130 tot 180 (?) originelen te achterhalen, de meesten heeft hij ook daadwerkelijk gezien en beoordeeld: Zie 2e PDF hier onderaan de pagina. Ik ga een poging doen om de 750 exemplaren van deze uitgave in kaart te brengen. Niet volledig willen zijn, maar dat wat ik eenvoudig kan achterhalen wel documenteren. Door privacy regels blijft veel onbekend, daarom heb ik de bekende eind eigenaren vetgedrukt gemaakt.

| Nummer | Laatst bekende eigenaar | Locatie | Land | Updated | Opmerkingen |

| 045 | Linda Hall Library | Kansas City | USA | 20220212 | Loanable ! |

| 058 | Alden Library Ohio University | Athens | Ohio | 20220217 | Enthousiaste mail terug met nummer onder de 200, foto’s gevraagd: handgekleurde versie. Ontvangen, maar verschil niet te zien… |

| 079 | Forschungsbibliothek Gotha | Erfurt | Duitsland | 20220405 | B gr2° 1213 is een van hun 2 facsimiles. (Zie 330) |

| 173 | National Library of the Czech Republic | Praag | Tsjechie | 20220212 | Ligt in het Clementinum waar ik ben geweest. Ook hebben ze niet 1 maar 2 originelen liggen… |

| 181 | Swan Auction Galleries: Eigenaar Onbekend | New York | USA | 20140403 | Verkocht voor 2.000 $ |

| 185 | Folger Shakespeare Library | Washington | USA | 20220212 | Miranda search tool (?) |

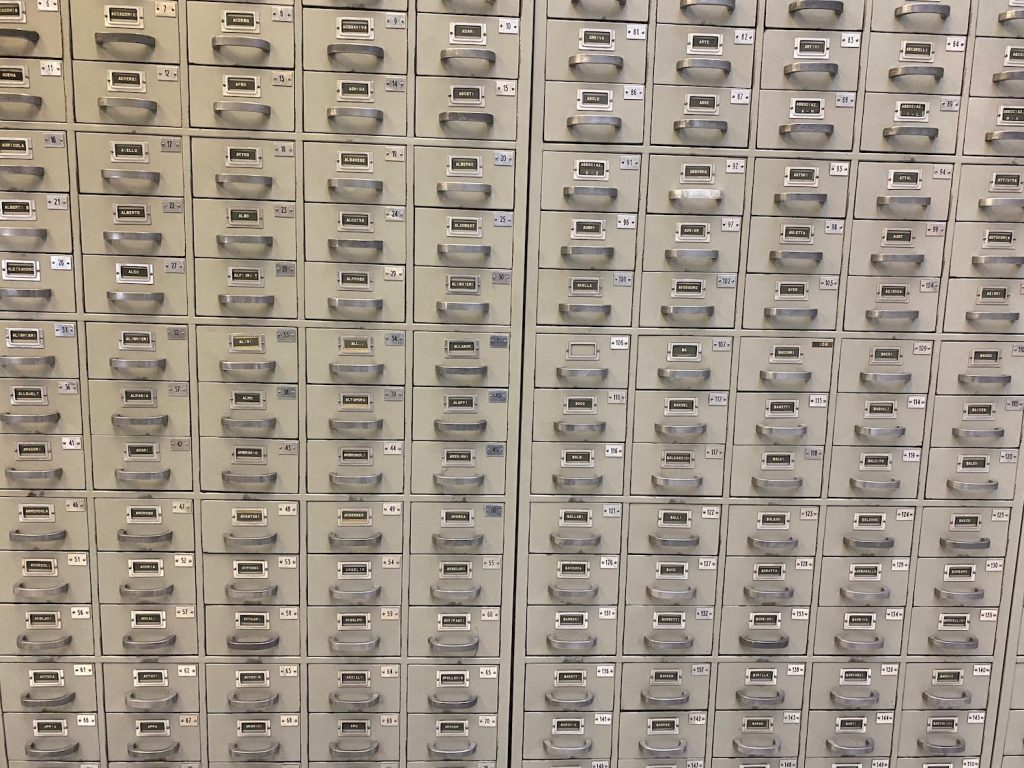

| 255 | Bibliotheca Centrale Nationale di Firenze | Firenze | Italie | 20230309 | Daargeweest en zelf opgezocht in hun systeem: zie hieronder op de foto’s. Niet bekeken ivm bureaucratie aldaar, zoals te verwachten met zo’n index systeem 😉 |

| 256 | University of Wisconsin – Madison | Wisconsin | USA | 20120212 | |

| 282 | Brown University Library | Providence, | USA | 20220212 | Rhode Island |

| 330 | Forschungsbibliothek Gotha | Erfurt | Duitsland | 20220405 | B gr2° 1144 is hun tweede facsimile (zie 079) |

| 332 | Museum Boerhaave | Leiden | Nederland | 20220212 | Ingezien |

| 334 | Universiteitsbibliotheek Gent | Gent | Belgie | 20120214 | Keurig en snel terug gemaild: nummer ontvangen. Schitterende stad ook… |

| 364 | Paralos Ltd. Antique Books > Sold to Bob McN | London | UK | 20240911 | Verkocht voor ongeveer 850 GBP in feb 2002 aan lid van de Vintage Astronomy Books FB groep. |

| 369 | Bas Griffioen | Schaijk | Nederland | 20220212 | Mijn exemplaar |

| 408 | Marc H. | Luxemburg | Luxemburg | 20220212 | Lid FB Vintage Astronomy Books |

| 440 | Alan Foljambe, bookseller: Eigenaar onbekend | Kingston | Canada | 20191231 | Gekocht via veiling Swann Galeries op 20191010 voor 1.188 $. Nu weer te koop via Barnebys.com voor 2.100 $ |

| 441 | Bellmans Fine Art auction | Sussex | UK | 20210700 | Niet verkocht op veiling van juli 2021. Nieuwe poging op 20211209. Gemaild voor nummer. |

| 516 | Doyle Gallery Auction: Eigenaar onbekend | New York | USA | 20151123 | Verkocht voor 1.250 $ |

| 523 | The Huntington Library | San Marino, California | USA | 20220217 | Hebben 2 facsimiles en 1 origineel in hun collectie |

| 533 | Christies Veiling: Eigenaar onbekend | New York | USA | 20080617 | Verkocht voor 1.375 $ |

| 547 | Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Library | New York | USA | 20250208 | Door Corona nu pas antwoord gekregen op mijn vraag van 20220212: 3 jaar na dato… 😉 |

| 589 | Te koop geweest op Ebay | Los Angeles | USA | ??? | Gevonden via WorthPoint, maar details onbekend |

| ??? | Ziereis Facsimiles | Regensburg | Duitsland | 20220212 | Willen nummers niet delen ivm privacy (?) Gaven wel aan dat ze er 11 hebben verkocht de laatste jaren… |

| ??? | Otis college of Art – Millard Sheets Library | Los Angeles | US | 20220110 | Gemaild voor nummer |

| ??? | Institut de Robotica i informatica Industrial | Barcelona | Spanje | 20220212 | Gemaild voor nummer |

| ??? | Central University Librabry of Cluj-Napoca | Cluj-Napoca | Roemenie | 20220212 | Nog contacten |

| ??? | Universität Siegen | Siegen | Duitsland |

Nummer 255 heb ik gevonden in Florence toen ik daar was voor een studiereis rondom Galilei. Die hoe in de index kamer 3 verdiepingen met kasten staan, elke verdieping heeft tientallen kasten, elk kast heeft 100+ laatjes en elk laatje heeft 300+ kaartjes. Op een ervan vond ik dat ze hier nummer 255 hebben…. Terug naar 1540 😉

Vergelijking handgeschilderde en gedrukte facsimiles

Miriam van de Alden Library in Ohio was zo aardig om enkele foto’s te maken van speciale pagina’s. Had ik haar gevraagd omdat hun nummer 58 is en dus bij de eerste 200 behoord en met de hand ingekleurd zou moeten zijn. Echter zijn ze exact hetzelfde als de pagina’s in mijn versie met nummer 369. Nog even uitzoeken dus: Altijd begrepen dat het de eerste 200 stuks waren die handgekleurd zijn… Of zou het 200 extra zijn…

Ik heb nummer 369 en zit dus niet bij de eerste 200 stuks. Dus ik had Miriam Intrator gevraagd wat foto’s te sturen omdat het nummer van hun editie 58 is, bij de eerste 200 dus. Ik had verwacht foto’s van een handgekleurde editie te krijgen, maar onze versies waren exact hetzelfde. Het is dus niet 200 van de 750 die handgekleurd waren, maar het lijkt meer op 200 plus 750 stuks. Henk Bril uit de FB groep Vintage Astronomy Books ging mee op zoek naar een antwoord en vond 2 geweldige startpunten !!!! Super blij mee, maar nog niet helemaal helder of opgelost….

Ook Anke van Forschungsbibliothek Gotha in Erfurt ziet hetzelfde bij de twee versies die zij hebben: “We have 2 copies as facsimile editions: signature B gr2° 1144 and B gr2° 1213. B gr2° 1144 is registered as number 330 and B gr2° 1213 is registered as number 79. Both bookplates in the text volume contain the following information “The total edition of this numbered facsimile edition is 750 copies. It is based on the original (Sign. Math. Fol. p. 38) of the Gotha State Library. The copies 1-200 were completely colored after the original in the Bavarian State Library Sign. rar 819).” Both facsimile editions are colored.” + “The difference between the two copies is the coloring of the initials. In copy no. 79 (signature B gr2° 1213) the initials are colored, in the other copy with no. 330 they are not. In our original copy (Math gr2° 38/2) the initials are also not colored.”

De normale editie was dus gebaseerd op het origineel van Tycho Brahe uit Gotha. Er staat niet bij wat de oplage was. Ik zou zeggen 550. De Special Edition gebaseerd op die van de state library uit München, zeker is dat daar maar 200 versies van zijn gemaakt. Of…. Was de nummering andersom: begonnen met 1 tot 550 of 750 en daarna pas de 200 speciale versies. Dan zou ik juist een van de hogere nummers in moeten zien / foto’s ontvangen: Ik heb echter nog geen duidelijke eigenaar gevonden in de hogere nummers… (Inmiddels wel, zie boven)

Duur grapje ook. 1.800 of 1.950 MDN (Mark der Deutschen Notenbank.) zoals die oostduitse munt toen (tot in 1967) heette. Ik kan de wisselkoers tov de oude Oost-Duitse Marken nog niet achterhalen, lijkt op een kwart van de waarde, maar aan de andere kant van de muur was alles ook weer veel goedkoper, dus wellicht Ostmarken maar lezen als Duitse Marken…

Nog een vergelijking, page by page

In 2024 laaide mijn interesse weer op doordat Lars een ‘The hidden volvelle’ had uitgewerkt tot een werkende papieren rekenmachine. Daardoor weer een vergelijking gemaakt met hulp van de Vintage Astronomy Books Facebook groep. Links nummer 181 die hier ooit verkocht werd. Rechts de foto’s van mijn eigen nummer 369. Ik zie geen verschil, behalve dan in kwaliteit, nummer 181 heeft wat meer geleden…

Vergelijking origineel en facsimile – side by side

Ik heb natuurlijk zelf het origineel in handen gehad en van elke pagina een foto gemaakt. Ook heb ik van de facsimile nummer 332 van Museum Boerhaave foto’s van elke pagina. Tijd om ze eens even naast elkaar te zetten en te vergelijken (voor zover mogelijk op dit formaat, en de kwaliteit van de foto’s doet natuurlijk ook nog iets…) Verschillend zijn wel direct zichtbaar in kleurtoepassing, maar da’s logisch en juist leuk: allemaal met de hand ingekleurd en dus niet een boek gelijk aan een ander… Het overzicht is niet compleet, slechts enkele pagina’s ontbreken: 13, 14, 18, 28, 29, 30, 34, omdat ik er geen foto’s van gemaakt heb toen ik het origineel bekeek. 21 is interessant omdat die compleet afwijkt tussen origineel en facsimile. Links staat het origineel en rechts foto’s van facsimile 332 (100% vergelijkbaar met mijn editie 369)

Natuurlijk zijn kleuren anders door belichting en camera, maar los daarvan zijn er ook enkele duidelijke afwijkingen tussen dit origineel en de facsimile uitgave:

– Bij nummer 4 is in de 2 maatranden een hele andere kleurcombinatie gebruikt

– De sierhangers boven aan de volbelles hebben geen meetkundige waarde en zijn redelijk vrij ingevuld, met veel onderlinge afwijkingen dus.

– Bij nummer 22 zijn in de ‘pizzapunt’ bovenin meer kleuren gebruikt

– 23 heeft twee totaal verschillende achtergrondkleuren: rood en blauw

– 27 is veelkleurig en heeft flinke afwijkingen daardoor.

– Bij 31 is niet alleen een andere kleurcombinatie toegepast, maar ook een andere stijl

– Ook bij 32 hele andere kleuren gebruikt: was de andere kleur op, foutje, vrijheid voor de ‘inkleurder’ ?

Dan zijn er nog de fouten betreft Volvelles 2, 14 en 21. Wat je nu ziet bij 21B zou normaliter helemaal niet zichtbaar zijn geweest. Onderstaand zie je op deze drie genoemde pagina’s dus grote verschillen tussen origineel een facsimile…

Overige info

Ik had mijn boek heel graag willen vergelijken met het origineel in Leiden, maar er is niet ‘het’ origineel. Omdat ze allemaal handgekleurd zijn is elk origineel anders. Hier bijvoorbeeld scans van de versie uit de bibliotheek van Wenen: Pagina voorin niet gekleurd en nog een heel ander wapen voor Apianus (nog niet koninklijk: Na die ‘beëdiging’ heeft hij nieuwe pagina’s gedrukt en vervangen) De curator hield het tegen omdat het geen wetenschappelijk nut had: zonde, was toch mooi geweest om de kwaliteit van de facsimile te bekijken, niet wetenschappelijk, wel gaaf om te doen…

Owen Gingerich beschrijft in een artikel (zie onderaan de pagina als PDF) genaamd “Peter Apian: Astronomie, Kosmographie und Mathematik am Beginn der Neuzeit (Polygon, 1995)” hoe de versie uit de Bibliotheek Thysiana in Leiden slordig hersteld is, niet compleet is en een originele standaard uitgave is (het eerste van 3 mogelijke wapenschilden)

Keizerlijk wapen voor Apianus

“Peter Apianus, keizerlijk Mathematicus, de heilige Lateraanse Palts in Roma, de kaiserl. en Romeins koninklijk Hofes en de Reich Consistorii Comes, geeft Martin Mayrhauser een wapen (vierkant, veld 1 en 4: blauwe pijl met S op goud; veld 2 en 3: vier diagonale balken in afwisselende kleuren blauw en goud); (De pauselijke en keizerlijke notaris Wilhelmus Lächholtz ex diocesi Frisingensi bevestigde de authenticiteit van het overgelegde document van Karel V bij de verlening van de titel van paltsgraaf aan Petrus Apianus (ingevoegd)).”

Meer informatie

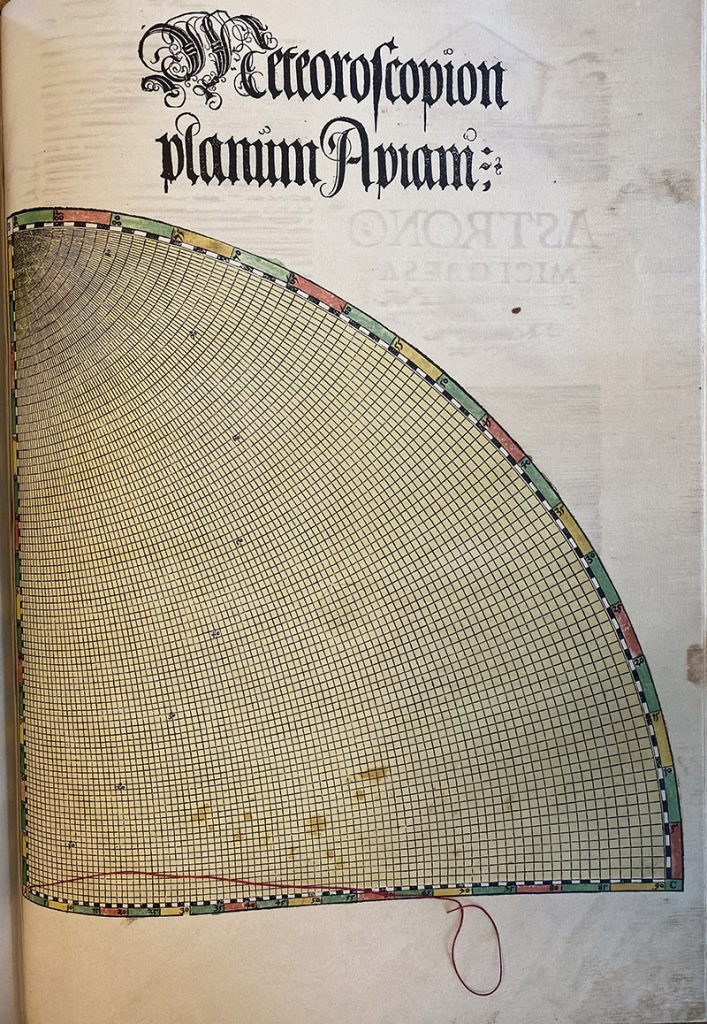

Beschrijving in Engels: The handbook is divided in two parts. The first (ll. B1–M3) includes 40 chapters with maps reproducing the position and the movement of celestial bodies. The second part describes the meteroscope, an instrument designed to solve problems in spherical trigonometry, and relates the sighting of five comets: “The Astronomicon is notable for Apian’s pioneer observations of comets (he describes the appearances and characteristics of five comets, including Halley’s) and his statement that comets point their tails away from the sun. Also important is his imaginative use of simple mechanical devices, particularly volvelles, to provide information on the position and movement of celestial bodies” (DSB).

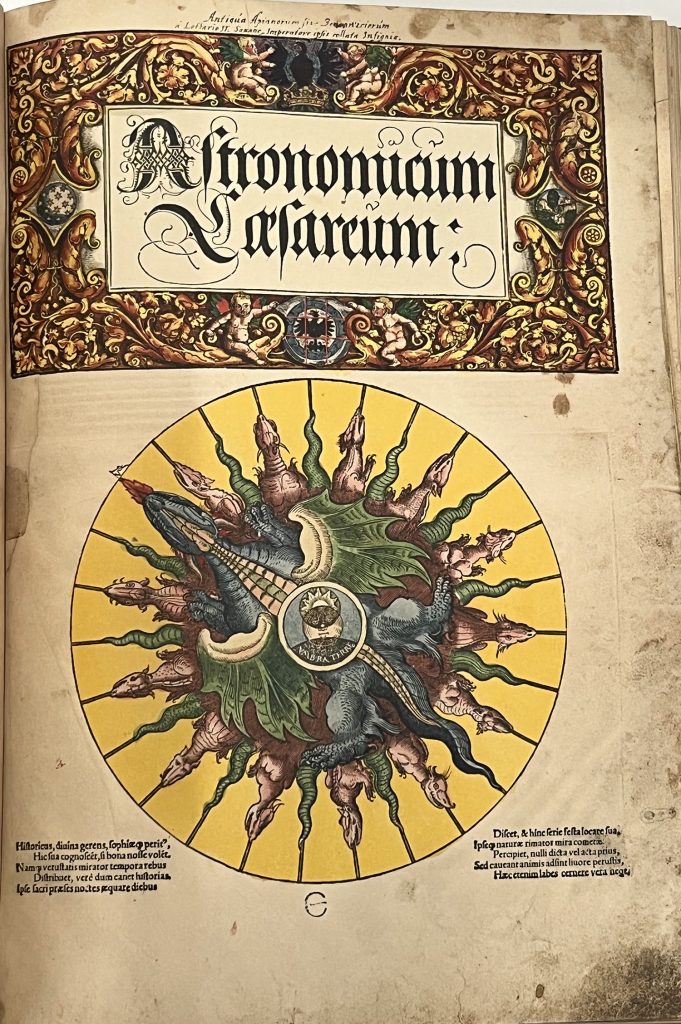

The volvelles in the work are each placed within a frame reminiscent of an astrolabe, a contemporary device that modelled the movement of the heavens in two dimensions and enabled the calculation of time and place, and assisted with astrology. The first moveable woodcut, which represents the planispheric astrolabe, compresses both hemispheres onto one plate. According to the text, the plate depicts 1,033 stars, and was based on the first printed star charts published in 1515 by Albrecht Dürer.

The most spectacular of the volvelles, which are the work of the artist Michael Ostendorfer, are the dragon plates. These include the title-page and the double-page spread dragon and moon dials. The dragon dial can be used to calculate the nodes of the moon, the two points of intersection between the yearly path of the sun, and the plane of the lunar orbit, which produce eclipses. Dragons were associated with eclipses, which were believed to occur when their head or tail blocked the sun. The thirteen small dragons indicate different parts of the lunar cycle.

Beschrijving 2: Apian, humanist mathematician and astronomer and born Bienewitz in Leisnig, Saxony (Biene is German for bee, hence the Latinizing of his name to Apian), was the son of a prosperous shoemaker and studied in Vienna, Regensburg and Landshut where he produced his Cosmographicus liber (1524), a highly respected work on astronomy and navigation which was to see at least 30 reprints in 14 languages and that remained popular until the end of the 16th century. In 1527 he was called to the University of Ingolstadt as a mathematician and printer and by the 1530s had secured the patronage of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. Apian’s purpose in writing Astronomicum Caesareum was to explain astronomy without recourse to the complicated mathematics involved: particularly for his patron Charles and his brother King Ferdinand to whom the book was dedicated and for whom it was named. The book took approximately 8 years to produce: from the issue of the patent in 1532 to the colophon dated 1540. The main contemporary use of the book would have been to cast horoscopes.

The book uses volvelles as a way to represent the functions of the astrolabe, an instrument used to take astronomical measurements. The volvelles contain as many as five independently rotatable paper dials that can be used to measure astronomical movement. The silk strings provide fiducial lines (a line assumed as a fixed base for comparison) and the strings are threaded with pearls to mark a point on the line. The volvelles and supporting tables can be used to calculate eclipses and Apian devotes 2 chapters to the correction of historical dates by reference to these phenomena. The book is based on Ptolemy’s geocentric model of the solar system which would begin to be overtaken just 3 years after the book’s publication when Copernicus published his De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, promoting the heliocentric model.

Nog iets moois gevonden: Tycho Brahe records that he paid twenty florins for one, which would be roughly equivalent to 3,000 dollars. A few books printed after 1540 managed to include even more complex assemblies of paper disks, but none achieved the total elegance and splendor of this volume. A triumph of the printer’s art, the Astronomicum Caesareum truly remains an astronomy fit for an emperor.

Originele verkoopprijzen in 1967: The Book as a Scientific Instrument: Astronomicum Caesareum. Peter Apianus. Facsimile of the 1540, Ingolstadt, edition, 122 pp., illus., with a companion volume, Peter Apianus und sein Astronomicum Caesareum,including a facsimile of Apianus’ German commentary and an introduction, in German and English, by Diedrich Wattenberg, 108 pp., illus. Edition Leipzig, Leipzig, 1967. Regular numbered edition, $465.50; special edition of 200 handcolored and numbered copies, $489.50.

Intekenprijs 1900 DM: Dit bericht rijmt niet met het stukje tekst erboven. In die tijd was de gulden even veel waard als de Duitse mark.

Interessante PDF’s over origineel en facsimile.

Lars schreef een paper over mijn ‘vondst’ en was zo netjes om mij daar de credits voor te geven. Ook noemt hij mijn presentatie “Beautiful Mistakes” die ik zelf over dit onderwerp maakte voor The Conference of the Antique Telescope Society in 2022. Over het Journal

Informatie die ik kreeg nagestuurd door Librairie Clavreuil:

Het artikel van kenner Owen Gingerich uit 1995 waarbij hij alle 111 onderzochte originele edities localiseert, waardeert en codeert:

Een van de beste beschrijvingen is van de hand van Lars Gislend van de Lund Universiteit bij Malmø in Zweden. De PDF is te groot om hier te plaatsen, maar het 18 MB origineel kun je downloaden op de site van de Universiteit. Hier wel twee losse artikelen van zijn hand: het laat al vlot zien dat het niet alleen fraaie boekdrukkunst was, maar ook echt wel complexe astronomie achter zat. [Bron1] [Bron2] [Bron3]